User:Lijianqu/金刚石晶体缺陷

en:Crystallographic defects in diamond

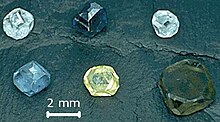

晶体结构的完美的周期性排列规律被破坏的情况称为晶体缺陷,金刚石晶体缺陷是金刚石晶体中的常见现象。金刚石晶体缺陷产生的原因有多种,如晶格不规则性、外来替代杂质或填隙杂质,这些杂质可能是金刚石生长过程中或生长完成后引入的。晶体缺陷会影响金刚石材料性质,决定金刚石类型。金刚石最明显受晶体缺陷影响的性质是颜色和电导率。晶体缺陷的影响可由能带理论解释。

金刚石晶体缺陷可由多种谱学技术检测,如电子自旋共振(EPR)、 光致发光(PL)、电子束(阴极发光,CL)、红外吸收光谱 (IR)、可见光和紫外光谱。吸收光谱学不仅用于识别缺陷,还能还能估算缺陷浓度,还能分辨天然钻石与合成钻石和优化钻石。[1]

标定金刚石中心

[编辑]金刚石谱学里有个传统,用标有数字的字母缩写标记缺陷致光谱,如GR1。这一传统有值得注意的例外,如A、B、C中心。许多字母缩写易使人混淆[2]:

- 有些符号太相似(如3H和H3)。

- 偶尔会有EPR和可见光谱用相同的符号标记不同的中心的情况,如N3 EPR中心与N3 可见光中心无任何关系[3]。

- 尽管很多字母缩写是符合逻辑的,如N3(N是天然的(Natural)缩写,用于天然钻石),H3(H是加热的(heated)缩写,用于经加热或辐照处理的钻石), 许多缩写没有逻辑。特别是以下三个符合In particular, there is no clear distinction between the meaning of labels GR (普通辐射,general radiation), R (辐照,radiation) and TR (II型辐照,type-II radiation)没有太大差别[2]。

缺陷对称性

[编辑]晶体缺陷的对称性用点群描述。晶体缺陷没有空间平移对称性,因此比晶体结构的对称群要少。对于金刚石,目前为止,只发现具有如下对称性的缺陷:四面体 (Td)、立方体l (D2d), 三方 (D3d、C3v)、菱形 (C2v)、单斜 (C2h、 C1h, C2) 和三斜 (C1 或 CS)[2][4]。

由缺陷对称性可以预言很多光学性质。比如纯金刚石不会有单光子(红外)吸收,因为金刚石晶格具有反演中心。但是,如果有缺陷(即使是对称性很高的缺陷,如N-N 置换对)破坏了晶体中心对称性,就可以造成缺陷致红外吸收,这是测量金刚石里缺陷浓度的最常见的方法[2]。

高温高压下的合成金刚石[5] 或化学气相沉积方法合成金刚石[6][7],有对称性低于四面体的缺陷在晶体生长方向排列。这种排列也见于砷化镓[8],因此不是金刚石所独有。

外来缺陷

[编辑]元素分析显示,金刚石可含有多种杂质。金刚石里的杂质一般只有纳米大小,在 光学显微镜下不可见。另外,任何元素都有可能通过离子注入进入金刚石。杂质元素进入金刚石更重要的途径是在金刚石生长过程中以单个原子或小的原子团簇的形式进入金刚石晶体。到2008年,在金刚石中发现的杂质元素有氮、硼、氢、硅、 磷、 镍、钴,可能还有硫。已经确认金刚石中还会有锰[9] 和钨[10],但是这两种元素可能来自外来杂质。已检测到金刚石中还有孤立的铁原子[11],其来源后来有新的解释,与金刚石合成过程中产生的红宝石小粒子有关[12]。氧应该是金刚石中的主要杂质元素[13],但是还没有光谱学证据 [來源請求]。发现有两个电子自旋共振中心(OK1 and N3),认为来自氮氧复合物,但是只有间接证据支持,相应的浓度还非常低[14]。

氮

[编辑]金刚石中最常见的杂质是氮,在金刚石中的质量分数可达到1%[13]。以前人们认为,金刚石中所以的晶格缺陷都是结构异常造成的。后来研究发现,绝大多数金刚石都含有氮,并且构型多样。含氮分子在进入金刚石前一般会分解,所以氮大多数情况下以单个原子的形式进入金刚石晶格,但是,金刚石晶体中也有氮分子存在[15]。

金刚石的光吸收和其他材料性质都与氮含量和聚集态密切相关。尽管所有的聚集构型都会导致红外吸收,但是有些聚集形式常常是无色的,即几乎不吸收任何 可见光[2]。四种主要的氮形式如下:

C-氮中心

[编辑]C中心相应于电中性的单个取代氮原子,易见于These are easily seen in 电子顺磁共振(EPR)谱[16](在EPR谱里又称P1中心)。C中心使金刚石颜色呈深黄色到褐色,这样的金刚石归类为“Ib型”,俗称“金丝雀钻石”,为罕见的宝石类型。在高温高压下制备的合成金刚石绝大多数都含有高浓度的C-氮中心,其氮杂质来自大气或石墨原料。每10万碳原子有1个氮原子的金刚石带有黄色[17]。因为氮原子有5个价电子,比被它取代的碳原子多一个,可以作为深电子施主,即每个取代氮原子可以多给出一个电子,在带隙中形成一个施主能级。能量在约2.2 电子伏以上的光可以激发施主电子,使其进入 导带,因而产生黄色[18]。

C中心的特征红外吸收光谱在1344 cm−1处有一个尖锐的峰,在1130 cm−1处有1个 较宽的特征峰。在这些峰处的吸收一般用于测量单个氮原子杂质的浓度[19]。利用金刚石对波长约为260 nm的紫外光的吸收的测量方法因不可靠而被抛弃[18]。

金刚石中的受体缺陷会使C中心的氮原子成为离子,C中心转化为C+中心。C+中心的特征红外吸收光谱在1332 cm−1处有1个明锐的峰,在1115, 、1046 and 和950 cm−1处有较宽较低的峰[20]。

A-氮中心

[编辑]A中心可能是天然金刚石最常见的缺陷。A中心中取代1个中性最近邻氮原子对。A中心产生紫外吸收的阈值约为4 eV (310 nm, 即肉眼ke),因此不会使金刚石带上颜色。含有以A中心的主的氮杂质归类IaA型[21]。

A中心具有抗磁性,但是被紫外光或深受主离子化后会产生 电子顺磁共振谱W24,分析此谱,确认氮N=N结构[22]。

The A center shows an IR absorption spectrum with no sharp features, which is distinctly different from that of the C or B centers. Its strongest peak at 1282 cm−1 is routinely used to estimate the nitrogen concentration in the A form.[23]

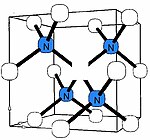

B-nitrogen center

[编辑]There is a general consensus that B center (sometimes called B1) consists of a carbon vacancy surrounded by four nitrogen atoms substituting for carbon atoms.[1][2][24] This model is consistent with other experimental results, but there is no direct spectroscopic data corroborating it. Diamonds where most nitrogen forms B centers are rare and are classed as type IaB; most gem diamonds contain a mixture of A and B centers, together with N3 centers.

Similar to the A centers, B centers do not induce color, and no UV or visible absorption can be attributed to the B centers. Early assignment of the N9 absorption system to the B center have been disproven later.[25] The B center has a characteristic IR absorption spectrum (see the infrared absorption picture above) with a sharp peak at 1332 cm−1 and a broader feature at 1280 cm−1. The latter is routinely used to estimate the nitrogen concentration in the B form.[26]

Note that many optical peaks in diamond accidentally have similar spectral positions, which causes much confusion among gemologists. Spectroscopists use for defect identification the whole spectrum rather than one peak, and consider the history of the growth and processing of individual diamond.[1][2][24]

N3 nitrogen center

[编辑]The N3 center consists of three nitrogen atoms surrounding a vacancy. Its concentration is always just a fraction of the A and B centers.[27] The N3 center is paramagnetic, so its structure is well justified from the analysis of the EPR spectrum P2.[3] This defect produces a characteristic absorption and luminescence line at 415 nm and thus does not induce color on its own. However, the N3 center is always accompanied by the N2 center, having an absorption line at 478 nm (and no luminescence).[28] As a result, diamonds rich in N3/N2 centers are yellow in color.

Boron

[编辑]Diamonds containing boron as a substitutional impurity are termed type IIb. Only one percent of natural diamonds are of this type, and most are blue to grey.[29] Boron is an acceptor in diamond: boron atoms have one less available electron than the carbon atoms; therefore, each boron atom substituting for a carbon atom creates an electron hole in the band gap that can accept an electron from the valence band. This allows red light absorption, and due to the small energy (0.37 eV)[30] needed for the electron to leave the valence band, holes can be thermally released from the boron atoms to the valence band even at room temperatures. These holes can move in an electric field and render the diamond electrically conductive (i.e., a p-type semiconductor). Very few boron atoms are required for this to happen—a typical ratio is one boron atom per 1,000,000 carbon atoms.

Boron-doped diamonds transmit light down to ~250 nm and absorb some red and infrared light (hence the blue color); they may phosphoresce blue after exposure to shortwave ultraviolet light.[30] Apart from optical absorption, boron acceptors have been detected by electron paramagnetic resonance.[31]

Phosphorus

[编辑]Phosphorus could be intentionally introduced into diamond grown by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) at concentrations up to ~0.01%.[32] Phosphorus substitutes carbon in the diamond lattice.[33] Similar to nitrogen, phosphorus has one more electron than carbon and thus acts as a donor; however, the ionization energy of phosphorus (0.6 eV)[32] is much smaller than that of nitrogen (1.7 eV)[34] and is small enough for room-temperature thermal ionization. This important property of phosphorus in diamond favors electronic applications, such as UV light emitting diodes (LEDs, at 235 nm).[35]

Hydrogen

[编辑]Hydrogen is one of the most technological important impurities in semiconductors, including diamond. Hydrogen-related defects are very different in natural diamond and in synthetic diamond films. Those films are produced by various chemical vapor deposition (CVD) techniques in an atmosphere rich in hydrogen (typical hydrogen/carbon ratio >100), under strong bombardment of growing diamond by the plasma ions. As a result, CVD diamond is always rich in hydrogen and lattice vacancies. In polycrystalline films, much of the hydrogen may be located at the boundaries between diamond 'grains', or in non-diamond carbon inclusions. Within the diamond lattice itself, hydrogen-vacancy[36] and hydrogen-nitrogen-vacancy[37] complexes have been identified in negative charge states by electron paramagnetic resonance. In addition, numerous hydrogen-related IR absorption peaks are documented.[38]

It is experimentally demonstrated that hydrogen passivates electrically active boron[39] and phosphorus[40] impurities. As a result of such passivation, shallow donor centers are presumably produced.[41]

In natural diamonds, several hydrogen-related IR absorption peaks are commonly observed; the strongest ones are located at 1405, 3107 and 3237 cm−1 (see IR absorption figure above). The microscopic structure of the corresponding defects is yet unknown and it is not even certain whether or not those defects originate in diamond or in foreign inclusions. Gray color in some diamonds from the Argyle mine in Australia is often associated with those hydrogen defects, but again, this assignment is yet unproven.[42]

Nickel and cobalt

[编辑]

When diamonds are grown by the high-pressure high-temperature technique, nickel, cobalt or some other metals are usually added into the growth medium to facilitate catalytically the conversion of graphite into diamond. As a result, metallic inclusions are formed. Besides, isolated nickel and cobalt atoms incorporate into diamond lattice, as demonstrated through characteristic hyperfine structure in electron paramagnetic resonance, optical absorption and photoluminescence spectra,[43] and the concentration of isolated nickel can reach 0.01%.[44] This fact is by all means unusual considering the large difference in size between carbon and transition metal atoms and the superior rigidity of the diamond lattice.[2][44]

Numerous Ni-related defects have been detected by electron paramagnetic resonance,[5][45] optical absorption and photoluminescence,[5][45][46] both in synthetic and natural diamonds.[42] Three major structures can be distinguished: substitutional Ni,[47] nickel-vacancy[48] and nickel-vacancy complex decorated by one or more substitutional nitrogen atoms.[45] The "nickel-vacancy" structure, also called "semi-divacancy" is specific for most large impurities in diamond and silicon (e.g., tin in silicon[49]). Its production mechanism is generally accepted as follows: large nickel atom incorporates substitutionally, then expels a nearby carbon (creating a neighboring vacancy), and shifts in-between the two sites.

Although the physical and chemical properties of cobalt and nickel are rather similar, the concentrations of isolated cobalt in diamond are much smaller than those of nickel (parts per billion range). Several defects related to isolated cobalt have been detected by electron paramagnetic resonance[50] and photoluminescence,[5][51] but their structure is yet unknown.[52]

Silicon

[编辑]

Silicon is a common impurity in diamond films grown by chemical vapor deposition and it originates either from silicon substrate or from silica windows or walls of the CVD reactor. It was also observed in natural diamonds in dispersed form.[53] Isolated silicon defects have been detected in diamond lattice through the sharp optical absorption peak at 738 nm[54] and electron paramagnetic resonance.[55] Similar to other large impurities, the major form of silicon in diamond has been identified with a Si-vacancy complex (semi-divacancy site).[55] This center is a deep donor having an ionization energy of 2 eV, and thus again is unsuitable for electronic applications.[56]

Si-vacancies constitute minor fraction of total silicon. It is believed (though no proof exists) that much silicon substitutes for carbon thus becoming invisible to most spectroscopic techniques because silicon and carbon atoms have the same configuration of the outer electronic shells.[57]

Sulfur

[编辑]Around the year 2000, there was a wave of attempts to dope synthetic CVD diamond films by sulfur aiming at n-type conductivity with low activation energy. Successful reports have been published,[58] but then dismissed[59] as the conductivity was rendered p-type instead of n-type and associated not with sulfur, but with residual boron, which is a highly efficient p-type dopant in diamond.

So far (2009), there is only one reliable evidence (through hyperfine interaction structure in electron paramagnetic resonance) for isolated sulfur defects in diamond. The corresponding center called W31 has been observed in natural type-Ib diamonds in small concentrations (parts per million). It was assigned to a sulfur-vacancy complex – again, as in case of nickel and silicon, a semi-divacancy site.[60]

参见

[编辑]参考资料

[编辑]- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Alan T. Collins. The detection of colour-enhanced and synthetic gem diamonds by optical spectroscopy. Diamond and Related Materials. 2003-10, 12 (10-11): 1976–1983 [2019-06-25]. doi:10.1016/S0925-9635(03)00262-0 (英语).

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 J Walker. Optical absorption and luminescence in diamond. Reports on Progress in Physics. 1979-10-01, 42 (10): 1605–1659 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0034-4885. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/42/10/001.

- ^ 3.0 3.1 J A van Wyk. Carbon-12 hyperfine interaction of the unique carbon of the P2 (ESR) or N3 (optical) centre in diamond. Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics. 1982-09-30, 15 (27): L981–L983 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0022-3719. doi:10.1088/0022-3719/15/27/007.

- ^ Zaitsev, A. M. Optical Properties of Diamond : A Data Handbook. Springer. 2001. ISBN 3-540-66582-X.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 K Iakoubovskii, A T Collins. Alignment of Ni- and Co-related centres during the growth of high-pressure–high-temperature diamond. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 2004-10-06, 16 (39): 6897–6906 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0953-8984. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/16/39/022.

- ^ A. M. Edmonds, U. F. S. D’Haenens-Johansson, R. J. Cruddace, M. E. Newton, K.-M. C. Fu, C. Santori, R. G. Beausoleil, D. J. Twitchen, M. L. Markham. Production of oriented nitrogen-vacancy color centers in synthetic diamond. Physical Review B. 2012-07-05, 86 (3) [2019-06-25]. ISSN 1098-0121. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.86.035201 (英语).

- ^ U. F. S. D’Haenens-Johansson, A. M. Edmonds, M. E. Newton, J. P. Goss, P. R. Briddon, J. M. Baker, P. M. Martineau, R. U. A. Khan, D. J. Twitchen, S. D. Williams. EPR of a defect in CVD diamond involving both silicon and hydrogen that shows preferential alignment. Physical Review B. 2010-10-15, 82 (15) [2019-06-25]. ISSN 1098-0121. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.82.155205 (英语).

- ^ R. A. Hogg, K. Takahei, A. Taguchi, Y. Horikoshi. Preferential alignment of Er–2O centers in GaAs:Er,O revealed by anisotropic host‐excited photoluminescence. Applied Physics Letters. 1996-06-03, 68 (23): 3317–3319 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0003-6951. doi:10.1063/1.116043 (英语).

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii, A. Stesmans. Characterization of Defects in as-Grown CVD Diamond Films and HPHT Diamond Powders by Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. physica status solidi (a). 2001-08, 186 (2): 199–206 [2020-07-07]. ISSN 0031-8965. doi:10.1002/1521-396X(200108)186:23.0.CO;2-R (英语).

- ^ S. Lal, T. Dallas, S. Yi, S. Gangopadhyay, M. Holtz, F. G. Anderson. Defect photoluminescence in polycrystalline diamond films grown by arc-jet chemical-vapor deposition. Physical Review B. 1996-11-15, 54 (19): 13428–13431 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0163-1829. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.54.13428 (英语).

- ^ K Iakoubovskii, G J Adriaenssens. Evidence for a Fe-related defect centre in diamond. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 2002-02-04, 14 (4): L95–L98 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0953-8984. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/14/4/104.

- ^ Konstantin Iakoubovskii, Guy J Adriaenssens. Comment on `Evidence for a Fe-related defect centre in diamond'. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 2002-06-03, 14 (21): 5459–5460 [2019-06-25]. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/14/21/401.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 W. Kaiser, W. L. Bond. Nitrogen, A Major Impurity in Common Type I Diamond. Physical Review. 1959-08-15, 115 (4): 857–863 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0031-899X. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.115.857 (英语).

- ^ M E Newton, J M Baker. 14 N ENDOR of the OK1 centre in natural type Ib diamond. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 1989-12-25, 1 (51): 10549–10561 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0953-8984. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/1/51/024.

- ^ Konstantin Iakoubovskii, Guy J Adriaenssens, Yogesh K Vohra. Nitrogen incorporation in diamond films homoepitaxially grown by chemical vapour deposition. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 2000-07-31, 12 (30): L519–L524 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0953-8984. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/12/30/106.

- ^ W. V. Smith, P. P. Sorokin, I. L. Gelles, G. J. Lasher. Electron-Spin Resonance of Nitrogen Donors in Diamond. Physical Review. 1959-09-15, 115 (6): 1546–1552 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0031-899X. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.115.1546 (英语).

- ^ Nassau, Kurt (1980) "Gems made by man" Gemological Institute of America, Santa Monica, California, ISBN 0-87311-016-1, p. 191

- ^ 18.0 18.1 K Iakoubovskii, G J Adriaenssens. Optical transitions at the substitutional nitrogen centre in diamond. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 2000-02-14, 12 (6): L77–L81 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0953-8984. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/12/6/102.

- ^ I. Kiflawi et al. "Infrared-absorption by the single nitrogen and a defect centers in diamond" Phil. Mag. B 69 (1994) 1141

- ^ Simon C Lawson, David Fisher, Damian C Hunt, Mark E Newton. On the existence of positively charged single-substitutional nitrogen in diamond. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 1998-07-13, 10 (27): 6171–6180 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0953-8984. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/10/27/016.

- ^ G Davies. The A nitrogen aggregate in diamond-its symmetry and possible structure. Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics. 1976-10-14, 9 (19): L537–L542 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0022-3719. doi:10.1088/0022-3719/9/19/005.

- ^ O. D. Tucker, M. E. Newton, J. M. Baker. EPR and N 14 electron-nuclear double-resonance measurements on the ionized nearest-neighbor dinitrogen center in diamond. Physical Review B. 1994-12-01, 50 (21): 15586–15596 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0163-1829. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.50.15586 (英语).

- ^ S. R. Boyd, I. Kiflawi, G. S. Woods. The relationship between infrared absorption and the A defect concentration in diamond. Philosophical Magazine B. 1994-06, 69 (6): 1149–1153 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 1364-2812. doi:10.1080/01418639408240185 (英语).

- ^ 24.0 24.1 引用错误:没有为名为

collins2的参考文献提供内容 - ^ A.A. Shiryaev, M.T. Hutchison, K.A. Dembo, A.T. Dembo, K. Iakoubovskii, Yu.A. Klyuev, A.M. Naletov. High-temperature high-pressure annealing of diamond. Physica B: Condensed Matter. 2001-12,. 308-310: 598–603 [2019-06-25]. doi:10.1016/S0921-4526(01)00750-5 (英语).

- ^ S. R. Boyd, I. Kiflawi, G. S. Woods. Infrared absorption by the B nitrogen aggregate in diamond. Philosophical Magazine B. 1995-09, 72 (3): 351–361 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 1364-2812. doi:10.1080/13642819508239089 (英语).

- ^ Anderson, B.; Payne, J.; Mitchell, R.K. (ed.) (1998) "The spectroscope and gemology", p. 215, Robert Hale Limited, Clerkwood House, London. ISBN 0-7198-0261-X

- ^ M. F. Thomaz, G. Davies. The Decay Time of N3 Luminescence in Natural Diamond. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 1978-08-22, 362 (1710): 405–419 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 1364-5021. doi:10.1098/rspa.1978.0141 (英语).

- ^ O'Donoghue, M. (2002) "Synthetic, imitation & treated gemstones", Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Great Britain. ISBN 0-7506-3173-2, p. 52

- ^ 30.0 30.1 The optical and electronic properties of semiconducting diamond. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A: Physical and Engineering Sciences. 1993-02-15, 342 (1664): 233–244 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0962-8428. doi:10.1098/rsta.1993.0017 (英语).

- ^ C A J Ammerlaan, R van Kemp. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in semiconducting diamond. Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics. 1985-05-10, 18 (13): 2623–2629 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0022-3719. doi:10.1088/0022-3719/18/13/009.

- ^ 32.0 32.1 T. Kociniewski, J. Barjon, M.-A. Pinault, F. Jomard, A. Lusson, D. Ballutaud, O. Gorochov, J. M. Laroche, E. Rzepka, J. Chevallier, C. Saguy. n-type CVD diamond doped with phosphorus using the MOCVD technology for dopant incorporation. physica status solidi (a). 2006-09, 203 (12): 3136–3141 [2019-06-25]. doi:10.1002/pssa.200671113 (英语).

- ^ Masataka Hasegawa, Tokuyuki Teraji, Satoshi Koizumi. Lattice location of phosphorus in n -type homoepitaxial diamond films grown by chemical-vapor deposition. Applied Physics Letters. 2001-11-05, 79 (19): 3068–3070 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0003-6951. doi:10.1063/1.1417514 (英语).

- ^ R.G. Farrer. On the substitutional nitrogen donor in diamond. Solid State Communications. 1969-05, 7 (9): 685–688 [2019-06-25]. doi:10.1016/0038-1098(69)90593-6 (英语).

- ^ S. Koizumi. Ultraviolet Emission from a Diamond pn Junction. Science. 2001-06-08, 292 (5523): 1899–1901 [2019-06-25]. doi:10.1126/science.1060258.

- ^ Claire Glover, M. E. Newton, P. M. Martineau, Samantha Quinn, D. J. Twitchen. Hydrogen incorporation in diamond: the vacancy-hydrogen complex. Physical Review Letters. 2004-04-02, 92 (13): 135502 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 15089622. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.135502.

- ^ Claire Glover, M. E. Newton, P. Martineau, D. J. Twitchen, J. M. Baker. Hydrogen Incorporation in Diamond: The Nitrogen-Vacancy-Hydrogen Complex. Physical Review Letters. 2003-05-09, 90 (18) [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0031-9007. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.185507 (英语).

- ^ F. Fuchs, C. Wild, K. Schwarz, W. Müller‐Sebert, P. Koidl. Hydrogen induced vibrational and electronic transitions in chemical vapor deposited diamond, identified by isotopic substitution. Applied Physics Letters. 1995-01-09, 66 (2): 177–179 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0003-6951. doi:10.1063/1.113126 (英语).

- ^ J. Chevallier, B. Theys, A. Lusson, C. Grattepain, A. Deneuville, E. Gheeraert. Hydrogen-boron interactions in p -type diamond. Physical Review B. 1998-09-15, 58 (12): 7966–7969 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0163-1829. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.58.7966 (英语).

- ^ J Chevallier, F Jomard, Z Teukam, S Koizumi, H Kanda, Y Sato, A Deneuville, M Bernard. Hydrogen in n-type diamond. Diamond and Related Materials. 2002-08, 11 (8): 1566–1571 [2019-06-25]. doi:10.1016/S0925-9635(02)00063-8 (英语).

- ^ Zéphirin Teukam, Jacques Chevallier, Cécile Saguy, Rafi Kalish, Dominique Ballutaud, Michel Barbé, François Jomard, Annie Tromson-Carli, Catherine Cytermann, James E. Butler, Mathieu Bernard, Céline Baron, Alain Deneuville. Shallow donors with high n-type electrical conductivity in homoepitaxial deuterated boron-doped diamond layers. Nature Materials. 2003-07, 2 (7): 482–486 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 1476-1122. doi:10.1038/nmat929 (英语).

- ^ 42.0 42.1 K Iakoubovskii, G.J Adriaenssens. Optical characterization of natural Argyle diamonds. Diamond and Related Materials. 2002-01, 11 (1): 125–131 [2019-06-25]. doi:10.1016/S0925-9635(01)00533-7 (英语).

- ^ Konstantin Iakoubovskii, Gordon Davies. Vibronic effects in the 1.4 − eV optical center in diamond. Physical Review B. 2004-12-09, 70 (24) [2019-06-25]. ISSN 1098-0121. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.70.245206 (英语).

- ^ 44.0 44.1 Alan T. Collins, Hisao Kanda, J. Isoya, C.A.J. Ammerlaan, J.A. van Wyk. Correlation between optical absorption and EPR in high-pressure diamond grown from a nickel solvent catalyst. Diamond and Related Materials. 1998-02, 7 (2-5): 333–338 [2019-06-25]. doi:10.1016/S0925-9635(97)00270-7 (英语).

- ^ 45.0 45.1 45.2 V A Nadolinny, A P Yelisseyev, J M Baker, M E Newton, D J Twitchen, S C Lawson, O P Yuryeva, B N Feigelson. A study of 13 C hyperfine structure in the EPR of nickel-nitrogen-containing centres in diamond and correlation with their optical properties. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 1999-09-27, 11 (38): 7357–7376 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0953-8984. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/11/38/314.

- ^ Larico, R.; Justo, J. F.; Machado, W. V. M.; Assali, L. V. C. Electronic properties and hyperfine fields of nickel-related complexes in diamond. Phys. Rev. B. 2009, 79: 115202. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.79.115202.

- ^ J. Isoya, H. Kanda, J. R. Norris, J. Tang, M. K. Bowman. Fourier-transform and continuous-wave EPR studies of nickel in synthetic diamond: Site and spin multiplicity. Physical Review B. 1990-03-01, 41 (7): 3905–3913 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0163-1829. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.41.3905 (英语).

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii. Ni-vacancy defect in diamond detected by electron spin resonance. Physical Review B. 2004-11-19, 70 (20) [2019-06-25]. ISSN 1098-0121. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.70.205211 (英语).

- ^ G. D. Watkins. Defects in irradiated silicon: EPR of the tin-vacancy pair. Physical Review B. 1975-11-15, 12 (10): 4383–4390 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0556-2805. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.12.4383 (英语).

- ^ D. J. Twitchen, J. M. Baker, M. E. Newton, K. Johnston. Identification of cobalt on a lattice site in diamond. Physical Review B. 2000-01-01, 61 (1): 9–11 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0163-1829. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.61.9 (英语).

- ^ Simon C. Lawson, Hisao Kanda, Kenji Watanabe, Isaac Kiflawi, Yoichiro Sato, Alan T. Collins. Spectroscopic study of cobalt-related optical centers in synthetic diamond. Journal of Applied Physics. 1996, 79 (8): 4348 [2019-06-25]. doi:10.1063/1.361744 (英语).

- ^ Larico, R.; Assali, L. V. C.; Machado, W. V. M.; Justo, J. F. Cobalt-related impurity centers in diamond: electronic properties and hyperfine parameters. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2008, 20: 415220. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/20/41/415220.

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii, G.J. Adriaenssens, N.N. Dogadkin, A.A. Shiryaev. Optical characterization of some irradiation-induced centers in diamond. Diamond and Related Materials. 2001-01, 10 (1): 18–26 [2019-06-25]. doi:10.1016/S0925-9635(00)00361-7 (英语).

- ^ C. D. Clark, H. Kanda, I. Kiflawi, G. Sittas. Silicon defects in diamond. Physical Review B. 1995-06-15, 51 (23): 16681–16688 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0163-1829. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.51.16681 (英语).

- ^ 55.0 55.1 A. M. Edmonds, M. E. Newton, P. M. Martineau, D. J. Twitchen, S. D. Williams. Electron paramagnetic resonance studies of silicon-related defects in diamond. Physical Review B. 2008-06-11, 77 (24) [2019-06-25]. ISSN 1098-0121. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.77.245205 (英语).

- ^ K. Iakoubovskii, G. J. Adriaenssens. Luminescence excitation spectra in diamond. Physical Review B. 2000-04-15, 61 (15): 10174–10182 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0163-1829. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.61.10174 (英语).

- ^ U. F. S. D'Haenens-Johansson, A. M. Edmonds, B. L. Green, M. E. Newton, G. Davies, P. M. Martineau, R. U. A. Khan, D. J. Twitchen. Optical properties of the neutral silicon split-vacancy center in diamond. Physical Review B. 2011-12-21, 84 (24) [2019-06-25]. ISSN 1098-0121. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.84.245208 (英语).

- ^ Isao Sakaguchi, Mikka N.-Gamo, Yuko Kikuchi, Eiji Yasu, Hajime Haneda, Toshimitsu Suzuki, Toshihiro Ando. Sulfur: A donor dopant for n -type diamond semiconductors. Physical Review B. 1999-07-15, 60 (4): R2139–R2141 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0163-1829. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.60.R2139 (英语).

- ^ R. Kalish, A. Reznik, C. Uzan-Saguy, C. Cytermann. Is sulfur a donor in diamond?. Applied Physics Letters. 2000-02-07, 76 (6): 757–759 [2019-06-25]. ISSN 0003-6951. doi:10.1063/1.125885 (英语).

- ^ J. M. Baker, J. A. van Wyk, J. P. Goss, P. R. Briddon. Electron paramagnetic resonance of sulfur at a split-vacancy site in diamond. Physical Review B. 2008-12-12, 78 (23) [2019-06-25]. ISSN 1098-0121. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.78.235203 (英语).