农业产生的温室气体排放

农业产生的温室气体排放(英语:Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture)数量庞大:由农业、林业和土地利用三个部门的排放,占全球排放量的13%至21%。[2]最终导致气候变化。农业的排放有两种:直接温室气体排放以及将森林等非农业用地转变为农业使用,而间接导致的排放。[3][4]农业温室气体排放中一氧化二氮和甲烷的排放量占总量的一半以上。[5] 畜牧业所产生的温室气体排放占整体农业排放的大部分,并耗用约30%的农业淡水用量。[6]

农业中的食物系统也是造成大量温室气体排放的来源,[7][8]除在大量土地利用及化石燃料使用时产生温室气体之外,也经由种植水稻和饲养牲畜等做法直接导致温室气体排放。[9]在过去250年来观测到的全球温室气体增加,三个主要原因是燃烧化石燃料、土地利用及农业活动。[10]饲养动物的消化系统有两类:单胃动物和反刍动物。用于生产牛肉和乳制品的牛是反刍动物,其温室气体排放量名列前茅,单胃动物,如猪只和家禽类的排放并不高。单胃动物具有更高的饲料转换效率,也不会产生很多甲烷。[7]二氧化碳是在农作物生长后期透过植物和土壤呼吸作用,被重新排放到大气中,导致更多的温室气体排放。[11]估计氮肥制造和使用过程中所产生的温室气体数量约占人为温室气体排放量的5%。减少化学肥料排放最重要的手段是减少其使用,同时也须将使用效率提高。[12]

有许多策略可用来减轻农业排放的影响,并进一步减少排放 - 此种做法统称为气候智能农业,其中的策略包括有提高畜牧业效率(包括管理和技术)、更有效的牲畜粪肥管理、降低对化石燃料和不可再生资源的依赖、动物进食和饮水时点与期间的调整,以及减少人类动物性食物的生产与消费。[7][13][14][15]这类策略可减少农业部门的温室气体排放,以实现更为永续的粮食系统。[16]:816–817

温室气体类别

[编辑]农业活动排放的温室气体包括二氧化碳、甲烷和一氧化二氮。[17]

二氧化碳

[编辑]犁田和种植农作物,以及运输活动等均会导致二氧化碳排放。[18]与农业相关的二氧化碳排放量约占全球温室气体排放量的11%。[19]减少犁田、减少闲置土地、将农作物生物质残留物归还土壤以及增加覆土作物等农业做法可减少二氧化碳排放。[20]

甲烷

[编辑]

牲畜产生的甲烷排放量是全球农业温室气体的第一大排放源。畜牧业排放的温室气体占人为温室气体排放总量的14.5%。单独一头牛每年就会排放220磅甲烷。[22]虽然甲烷于大气中的停留时间比二氧化碳短得多,但它捕获热量的能力却高出28倍。[22]牲畜不仅会造成有害的排放,还会使用大量土地,可能会因过度放牧,而导致土壤品质不健康和物种多样性减少。[22]减少甲烷排放的方法中包括改用植物为主的饮食(少吃肉)、以更有营养的饲料喂养牲畜、进行牲畜粪肥管理,以及堆肥。[23]

采传统方式种植水稻是仅次于牲畜的第二大农业甲烷来源,其产生短期的暖化影响相当于所有航空业的二氧化碳排放量(参见航空业对环境的影响)。[24]由于全球对玉米、小麦和牛奶等农产品的大量需求,导致各国政府于农业政策的参与度并不高,因此尚无有效的降低农业排放措施出现。[25]美国国际开发署 (USAID) 实施名为"养活未来"的全球饥饿和粮食安全倡议,预定同时解决粮食损失和浪费问题,透过解决粮食损失和浪费问题,还可解决温室气体排放问题。只关注12个国家20个价值链的乳制品系统,就可减少4-10%的粮食损失和浪费。[26]这是种有效的做法,即可减少温室气体排放,还能养活人口。[26]

一氧化二氮

[编辑]

一氧化二氮的排放是由于施用合成肥料和有机肥料数量增加后的结果,施肥可提高农作物的产量,并使农作物的生长速度加快。农业所排放的一氧化二氮占美国温室气体排放量的6%,自1980年以来,其于大气中的浓度已增加30%。[27]虽然6%的占比似乎数字不大,但一氧化二氮的捕热效率是二氧化碳的300倍,且于大气中停留的时间约为120年。[27]不同的管理法,例如透过滴灌以节约用水、监测土壤养分以避免过度施肥,以及使用覆土作物以代替施肥,将有助于减少一氧化二氮的排放。[28]

不同活动产生的排放

[编辑]土地利用变化

[编辑]

农业活动在土地利用方面,主要透过四种方式造成温室气体排放增加:

上述农业过程总共占甲烷排放量的54%、一氧化二氮排放量的约80%,以及几乎所有与土地利用相关的二氧化碳排放量。[30]

随着人类自1750年起为开发而砍伐温带地区的森林,导致地球土地覆盖发生重大变化。当森林和林地受砍伐以转作耕地和牧地用途时,受到影响地区的反照率会因此增加,根据当地条件,而会导致变暖或变冷效应。[31]森林砍伐也会影响区域RuBisCO再吸收,导致二氧化碳(主要温室气体)浓度增加。[32]因为刀耕火种等土地清理方法需燃烧生物质,会直接将温室气体和煤烟等悬浮微粒释放进入大气,更把这些影响加剧。土地清理行动会破坏土壤碳海绵,而影响当地的水循环。

牲畜

[编辑]

畜牧业和畜牧的相关活动(例如砍伐森林和日益密集使用化石燃料的耕作方式)导致占比超过18%[33]的人为温室气体排放,包括:

- 占全球二氧化碳排放量的9%

- 占全球甲烷排放量的35-40%(主要来自牲畜肠道发酵与其粪便)

- 占全球一氧化二氮排放量的64%(主要是由于使用化学肥料的结果。[33])

因为种植玉米和苜蓿等农作物是为喂养动物,导致畜牧业活动对土地利用的影响也特别巨大。

于2010年,来自牲畜肠道发酵所产生温室气体排放占全球所有农业活动总量的43%。[34]针对生命周期评估研究所做的统合分析,发现来自反刍动物的肉类比其他肉类或素食蛋白质来源具有更高的碳当量足迹。[35]每年全球绵羊和山羊等小型反刍动物排放的温室气体约为4.75亿吨(二氧化碳当量),约占世界农业部门排放量的6.5%。[36]动物(主要是反刍动物)产生的甲烷估计占全球甲烷产量的15-20%。[37][38]关于使用各种海藻物种(特别是Asparegpsis armata)作为助于减少反刍动物产生甲烷的饲料添加剂,研究工作仍在进行中。[39]

全球的畜牧业用地占所有农业用地的70%,即地球陆地表面的30%。[33]其中的放牧方式也会影响未来土地的肥力。不采循环放牧会造成土壤板结的后果。牧地的扩张会影响当地野生动物的栖息地,导致其数量变少。减少人类在肉类和乳制品的摄取是减少温室气体排放的另一有效方法。于2022年接受调查的欧洲人,其中略多于一半(51%) 支持人们为应对气候变化而减少购买的肉类和乳制品的数量,40%的美国人和73%的中国受访者也表达相同的看法。[40]

非营利研究与政策组织斯德哥尔摩环境研究所建议在公正转型过程中逐步取消对牲畜业的补贴。[41]

化学肥料生产

[编辑]氮肥制造和施用过程中,所产生的温室气体——二氧化碳、甲烷和一氧化二氮的数量估计约占人为温室气体排放量的5%。其中有三分之一是在生产过程中产生,三分之二是施肥过程中产生。最重要的减少排放方法是减少化学肥料的使用。于英国牛津大学任教的安德烈·卡布雷拉·塞伦霍(André Cabrera Serrenho)博士表示:"我们使用肥料的效率极其低下","我们施用的肥料远超出实际的需要"。[42]氮肥可被土壤中细菌转化为一氧化二氮(一种温室气体)[43]人类于2007年至2016年期间所排放的一氧化二氮(其中大部分来自化肥)估计为每年700万吨,[44]这排放量与把全球变暖限制在2°C以内的目标无法匹配。[45]

稻米生产

[编辑]

全球种植稻米所排放的温室气体总量比任何其他植物粮食都要多。[46]估计到2021年,其将占农业甲烷排放量的30%和农业一氧化二氮排放量的11%。[47]排放甲烷的原因是由于稻田长期被水覆盖,土壤无法吸收大气中的氧气,导致土壤中的有机物发生厌氧发酵过程的后果。[48]于2021年所做的一项研究估计稻米种植于2010年全球人为温室气体排放的470亿吨[49]中占有20亿吨。[46]这项研究将整个稻米种植的生命周期(包括生产、运输和消费)的温室气体排放量加总,并与全球不同食物总量比较。[50]稻米种植的总排放量是生产牛肉总排放量的一半。[46]

全球估计

[编辑]

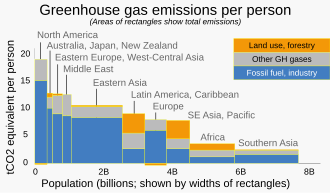

估计于2010年至2019年期间,全球农业、林业和土地利用所排放的温室气体占全球排放总量的13%至21%。[2]一氧化二氮和甲烷占农业温室气体排放总量的一半以上。[5]

估计到2020年,整个粮食系统会占全球温室气体排放总量的37%,由于人口增长和饮食习惯变化,这一占比到2050年将再增加30-40%。[51]

较早的估计

[编辑]估计农业、林业和土地利用变化于2010年占全球年排放量的20-25%。[16]:383

缓解

[编辑]| Food Types | 温室气体排放量 (每生产一克蛋白质所排放的二氧化碳当量(克) |

|---|---|

| 反刍动物肉类 | |

| 循环水养殖系统产品 | |

| 拖网捕捞鱼类 | |

| 水产养殖类 | |

| 猪肉 | |

| 家禽 | |

| 乳制品 | |

| 鱼类 | |

| 蛋类 | |

| 根类蔬菜 | |

| 小麦 | |

| 玉米 | |

| 豆类 |

于发达国家

[编辑]通常政府的减排计划中并未包括农业的排放。[53]例如欧盟排放交易体系[54]涵盖欧盟约40%的温室气体排放量,而给予农业部门排放控制的豁免。[55]

于发展中国家

[编辑]农业温室气体排放量占全球排放总量的四分之一以上。[57]由于农业产值仅占全球国内生产毛额 (GDP) 的比重约4%,这些数字显示农业活动产生过高比率的温室气体。创新的农业做法和技术可在气候变化缓解[58]和调适方面发挥功效。这种调适和缓解潜能在农业生产力仍然较低的发展中国家最为明显,当地的贫穷、气候变化脆弱性和粮食不安全依然严重,气候变化的直接影响会特别严重。在此背景下,建立机构及制定政策,开发必要的农业技术,并利用这些技术促使这些国家能够调整其农业系统以适应气候变化,而在多个层面发挥重要作用。

由国家或非政府组织资助的计划可帮助农民更具气候韧性,例如在降雨变得更加不稳定时可提供可靠水源的灌溉基础设施。[59][60]在雨季收集水以供干旱期间使用的集水系统也可减轻气候变化的影响。[60]一些项目,例如一项于危地马拉举办名为西方农村合作发展协会(Asociación de Cooperación para el Desarrollo Rural de Occidente (C.D.R.O.))的项目(由美国政府资助直至2017年),重点在关注混农林业和天气监测系统,以协助农民从事调适措施。此项目为居民提供资源,让他们在种植传统玉米的同时也种植新的、适应性更强的作物,以保护玉米生产免受温度变化、霜冻等影响。也建立天气监测系统来帮助预测极端天气事件,在发生之前向居民发送简讯以作因应。[61]

农业模型比对和改进计划 (Agricultural Model Intercomparison and Improvement Project ,简称AgMIP)[62]于2010年制定,目的为评估农业电脑模型并比较其预测气候影响的能力。AgMIP区域研究小组 (regional research teams,简称RRT) 正在撒哈拉以南非洲和南亚、南美洲和东亚进行全面评估,以提高对国家和区域内气候变化对农业影响(包括生物物理和经济影响(参见气候变化经济分析))的了解。其他AgMIP的倡议包括全球网格建模、数据和资讯技术 (IT) 工具开发、作物病虫害模拟、于特定场地测试的作物气候敏感性研究以及前述资讯的整合与扩展。

非政府组织全球常绿联盟(Global EverGreening Alliance )在2019年联合国气候行动峰会上宣布一项促进混农林业和保护性农业倡议。其目标之一是从大气中封存碳。联盟的目标是在575万平方公里的土地上为树木作复育工作,在650万平方公里的土地上实现健康的树草平衡,并在500万平方公里的土地上增加碳截存作用。预计这些复育的土地到2050年,每年可截存200亿吨的碳。倡议的第一阶段是"非洲大疏林草原绿化(Grand African Savannah Green Up)"计划。 迄2019年,已有数百万家庭采取这类做法,位于撒赫尔农场的平均树木覆盖面积已达到16%。[63]

气候智能农业

[编辑]所谓气候智能型农业 (CSA)(或称具有气候韧性农业(climate resilient agriculture))是种管理景观的综合方法,以协助施作方式、牲畜和农作物去适应气候变化的影响,并在可能的情况下通过减少农业温室气体排放来抵消气候变化的负面影响,同时针对不断增长的人口以确保粮食安全。[64]因此重点不仅在于碳耕作或可持续农业,还在于提高农业生产力。

CSA具有三大支柱:提高农业生产力和收入、调适和增强对气候变化的[[气候变化韧性|韧性}}以及减少或消除农业的温室气体排放。[65]CSA列出各种作物和植物应对未来挑战的行动。例如建议针对温度升高和热压力,栽种耐热作物、采用土壤覆盖、水资源管理、建造遮荫房、种植行间遮荫树、进行碳截存,[66]以及为牛只提供适当的牛舍与空间。[67]CSA致力于稳定作物生产,同时减轻气候变化的不利影响,并在最大限度内提高粮食安全。[68][69]

有人试图把CSA纳入核心政府政策、支出和规划框架中。为让CSA政策有效,这类措施必须能促进广泛的经济增长、永续发展目标和减贫。它们还必须与减灾战略、行动和社会安全网计划相结合。[70]参见

[编辑]参考文献

[编辑]- ^ Food production is responsible for one-quarter of the world's greenhouse gas emissions. Our World in Data. [2023-07-20].

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Nabuurs, G-J.; Mrabet, R.; Abu Hatab, A.; Bustamante, M.; et al. Chapter 7: Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Uses (AFOLU) (PDF). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. : 750 [2023-11-20]. doi:10.1017/9781009157926.009. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-03-07)..

- ^ Section 4.2: Agriculture's current contribution to greenhouse gas emissions, in: HLPE. Food security and climate change. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE) on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. June 2012: 67–69. (原始内容存档于2014-12-12).

- ^ Sarkodie, Samuel A.; Ntiamoah, Evans B.; Li, Dongmei. Panel heterogeneous distribution analysis of trade and modernized agriculture on CO2 emissions: The role of renewable and fossil fuel energy consumption. Natural Resources Forum. 2019, 43 (3): 135–153. ISSN 1477-8947. doi:10.1111/1477-8947.12183

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 FAO. Emissions due to agriculture. Global, regional and country trends 2000–2018. (PDF) (报告). FAOSTAT Analytical Brief Series 18. Rome: 2. 2020 [2023-11-20]. ISSN 2709-0078. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-04-28).

- ^ How livestock farming affects the environment. www.downtoearth.org.in. [2022-02-10]. (原始内容存档于2023-01-30) (英语).

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Friel, Sharon; Dangour, Alan D.; Garnett, Tara; et al. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: food and agriculture. The Lancet. 2009, 374 (9706): 2016–2025. PMID 19942280. S2CID 6318195. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61753-0.

- ^ The Food Gap: The Impacts of Climate Change on Food Production: a 2020 Perspective (PDF). 2011. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2012-04-16).

- ^ Steinfeld H, Gerber P, Wassenaar T, Castel V, Rosales M, de Haan C. Livestock's long shadow: environmental issues and options (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN. 2006. ISBN 978-92-5-105571-7. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2008-06-25).

- ^ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2007-05-01. (IPCC)

- ^ Sharma, Gagan Deep; Shah, Muhammad Ibrahim; Shahzad, Umer; Jain, Mansi; Chopra, Ritika. Exploring the nexus between agriculture and greenhouse gas emissions in BIMSTEC region: The role of renewable energy and human capital as moderators. Journal of Environmental Management. 2021-11-01, 297: 113316 [2023-11-20]. ISSN 0301-4797. PMID 34293673. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113316. (原始内容存档于2022-10-23) (英语).

- ^ Carbon emissions from fertilizers could be reduced by as much as 80% by 2050. Science Daily. University of Cambridge. [2023-02-17]. (原始内容存档于2023-02-17).

- ^ Thornton, P.K.; van de Steeg, J.; Notenbaert, A.; Herrero, M. The impacts of climate change on livestock and livestock systems in developing countries: A review of what we know and what we need to know. Agricultural Systems. 2009, 101 (3): 113–127. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2009.05.002.

- ^ Kurukulasuriya, Pradeep; Rosenthal, Shane. Climate Change and Agriculture: A Review of Impacts and Adaptions (PDF) (报告). World Bank. June 2003 [2023-11-20]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2017-01-18).

- ^ McMichael, A.J.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.H.; Corvalán, C.F.; et al. Climate Change and Human Health: Risks and Responses (PDF) (报告). World Health Organization. 2003 [2023-11-20]. ISBN 92-4-156248-X. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-03-28).

- ^ 16.0 16.1 Blanco G., R. Gerlagh, S. Suh, J. Barrett, H.C. de Coninck, C.F. Diaz Morejon, R. Mathur, N. Nakicenovic, A. Ofosu Ahenkora, J. Pan, H. Pathak, J. Rice, R. Richels, S.J. Smith, D.I. Stern, F.L. Toth, and P. Zhou, 2014: Chapter 5: Drivers, Trends and Mitigation (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). In: Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) [Edenhofer, O., R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K. Seyboth, A. Adler, I. Baum, S. Brunner, P. Eickemeier, B. Kriemann, J. Savolainen, S. Schlömer, C. von Stechow, T. Zwickel and J.C. Minx (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

- ^ Smith, Laurence G.; Kirk, Guy J. D.; Jones, Philip J.; Williams, Adrian G. The greenhouse gas impacts of converting food production in England and Wales to organic methods. Nature Communications. 2019-10-22, 10 (1): 4641. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.4641S. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6805889

. PMID 31641128. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-12622-7.

. PMID 31641128. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-12622-7.

- ^ Agricultural Practices Producing and Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions (PDF). [2023-11-20]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-03-15).

- ^ US EPA, OAR. Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions. www.epa.gov. 2023-02-08 [2022-04-04]. (原始内容存档于2022-09-27) (英语).

- ^ Food, Ministry of Agriculture and. Reducing agricultural greenhouse gases - Province of British Columbia. www2.gov.bc.ca. [2022-04-04]. (原始内容存档于2023-02-07).

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max; Rosado, Pablo. CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Our World in Data. 2020-05-11.

- ^ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Quinton, Amy. Cows and climate change. June 27, 2019 [2023-11-20]. (原始内容存档于2023-01-15).

- ^ Curbing methane emissions: How five industries can counter a major climate threat | McKinsey. www.mckinsey.com. [2022-04-04]. (原始内容存档于2023-05-11).

- ^ Reed, John. Thai rice farmers step up to tackle carbon footprint. Financial Times. 2020-06-25 [2020-06-25]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-09).

- ^ Leahy, Sinead; Clark, Harry; Reisinger, Andy. Challenges and Prospects for Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Mitigation Pathways Consistent With the Paris Agreement. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. 2020, 4. ISSN 2571-581X. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2020.00069

.

.

- ^ 26.0 26.1 Galford, Gillian L.; Peña, Olivia; Sullivan, Amanda K.; Nash, Julie; Gurwick, Noel; Pirolli, Gillian; Richards, Meryl; White, Julianna; Wollenberg, Eva. Agricultural development addresses food loss and waste while reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Science of the Total Environment. 2020, 699: 134318. Bibcode:2020ScTEn.699m4318G. PMID 33736198. S2CID 202879416. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134318

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ 27.0 27.1 The Greenhouse Gas No One's Talking About: Nitrous Oxide on Farms, Explained. Civil Eats. 2019-09-19 [2022-04-04]. (原始内容存档于2022-12-07) (英语).

- ^ University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources. Nitrous Oxide Emissions. ucanr.edu. [2022-04-04]. (原始内容存档于2023-03-07) (美国英语).

- ^ Fig. SPM.2c from Working Group III. Climate Change 2022 / Mitigation of Climate Change / Summary for Policymakers (PDF). IPCC.ch (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). 2022-04-04: 10. ISBN 978-92-9169-160-9. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-07-22). GDP data is for 2019.

- ^ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) retrieved 2007-06-26

- ^ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (PDF). [2023-11-20]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2007-12-15).

- ^ IPCC Technical Summary (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) retrieved 2007-06-25

- ^ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Steinfeld H, Gerber P, Wassenaar TD, Castel V, de Haan C. Livestock's Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options (PDF). Food & Agriculture Org. 2006-01-01. ISBN 9789251055717. (原始内容存档于2008-06-25) –通过Google Books.,

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2013) "FAO STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 2013 World Food and Agriculture" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). See data in Table 49.

- ^ Ripple WJ, Smith P, Haberl H, Montzka SA, McAlpine C, Boucher DH. Ruminants, climate change and climate policy. Nature Climate Change. 2013-12-20, 4 (1): 2–5. Bibcode:2014NatCC...4....2R. doi:10.1038/nclimate2081.

- ^ Giamouri, Elisavet; Zisis, Foivos; Mitsiopoulou, Christina; Christodoulou, Christos; Pappas, Athanasios C.; Simitzis, Panagiotis E.; Kamilaris, Charalampos; Galliou, Fenia; Manios, Thrassyvoulos; Mavrommatis, Alexandros; Tsiplakou, Eleni. Sustainable Strategies for Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction in Small Ruminants Farming. Sustainability. 2023-02-24, 15 (5): 4118. ISSN 2071-1050. doi:10.3390/su15054118

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ Cicerone RJ, Oremland RS. Biogeochemical aspects of atmospheric methane.. Global Biogeochemical Cycles. December 1988, 2 (4): 299–327 [2023-11-20]. Bibcode:1988GBioC...2..299C. S2CID 56396847. doi:10.1029/GB002i004p00299. (原始内容存档于2023-11-04).

- ^ Yavitt JB. Methane, biogeochemical cycle.. Encyclopedia of Earth System Science (London, England: Academic Press). 1992, 3: 197–207.

- ^ Hughes, Lesley. From designing clothes to refashioning cow burps: Sam's $40 million career switch. The Sydney Morning Herald. 2022-09-02: 8–11 [2023-03-22]. (原始内容存档于2022-12-05).

- ^ 2022-2023 EIB Climate Survey, part 2 of 2: Majority of young Europeans say the climate impact of prospective employers is an important factor when job hunting. EIB.org. [2023-03-22]. (原始内容存档于2023-12-07) (英语).

- ^ just-transition-meat-sector (PDF). [2023-11-20]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-03-06).

- ^ Carbon emissions from fertilizers could be reduced by as much as 80% by 2050. Science Daily. University of Cambridge. [2023-02-17]. (原始内容存档于2023-02-17).

- ^ How Fertilizer Is Making Climate Change Worse. BloombergQuint. September 2020-09-10 [2021-03-25]. (原始内容存档于2022-04-29) (英语).

- ^ Tian, Hanqin; Xu, Rongting; Canadell, Josep G.; Thompson, Rona L.; Winiwarter, Wilfried; Suntharalingam, Parvadha; Davidson, Eric A.; Ciais, Philippe; Jackson, Robert B.; Janssens-Maenhout, Greet; Prather, Michael J. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature. October 2020, 586 (7828): 248–256. Bibcode:2020Natur.586..248T. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 33028999. S2CID 222217027. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2780-0. hdl:1871.1/c74d4b68-ecf4-4c6d-890d-a1d0aaef01c9

. (原始内容存档于2020-10-13) (英语). Alt URL (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

. (原始内容存档于2020-10-13) (英语). Alt URL (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Nitrogen fertiliser use could 'threaten global climate goals'. Carbon Brief. 2020-10-07 [2021-03-25]. (原始内容存档于2024-01-19) (英语).

- ^ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Meat accounts for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gases from food production, study finds. The Guardian. 2021-09-13 [2021-10-14]. (原始内容存档于2023-10-07) (英语).

- ^ Gupta, Khushboo; Kumar, Raushan; Baruah, Kushal Kumar; Hazarika, Samarendra; Karmakar, Susmita; Bordoloi, Nirmali. Greenhouse gas emission from rice fields: a review from Indian context. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. June 2021, 28 (24): 30551–30572. PMID 33905059. S2CID 233403787. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-13935-1.

- ^ Neue, H.U. Methane emission from rice fields: Wetland rice fields may make a major contribution to global warming. BioScience. 1993, 43 (7): 466–73 [2008 -02-04]. JSTOR 1311906. doi:10.2307/1311906. (原始内容存档于2008-01-15).

- ^ Charles, Krista. Food production emissions make up more than a third of global total. New Scientist. [2021-10-14]. (原始内容存档于2024-02-03).

- ^ Xu, Xiaoming; Sharma, Prateek; Shu, Shijie; Lin, Tzu-Shun; Ciais, Philippe; Tubiello, Francesco N.; Smith, Pete; Campbell, Nelson; Jain, Atul K. Global greenhouse gas emissions from animal-based foods are twice those of plant-based foods=. Nature Food. September 2021, 2 (9): 724–732. ISSN 2662-1355. PMID 37117472. S2CID 240562878. doi:10.1038/s43016-021-00358-x. hdl:2164/18207

.

.

- ^ ((Science Advice for Policy by European Academies)). A sustainable food system for the European Union (PDF). Berlin: SAPEA. 2020: 39 [2020-04-14]. ISBN 978-3-9820301-7-3. doi:10.26356/sustainablefood. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2020-04-18).

- ^ Michael Clark; Tilman, David. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature. November 2014, 515 (7528): 518–522. Bibcode:2014Natur.515..518T. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 25383533. S2CID 4453972. doi:10.1038/nature13959.

- ^ Livestock – Climate Change's Forgotten Sector: Global Public Opinion on Meat and Dairy Consumption. www.chathamhouse.org. 2014-12-03 [2021-06-06]. (原始内容存档于2023-12-25) (英语).

- ^ Barbière, Cécile. Europe's agricultural sector struggles to reduce emissions. www.euractiv.com. 2020-03-12 [2021-06-06]. (原始内容存档于2023-10-26) (英国英语).

- ^ Anonymous. EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). Climate Action - European Commission. 2016-11-23 [2021-06-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-05-05) (英语).

- ^ Vermeulen SJ, Dinesh D. 2016. Measures for climate change adaptation in agriculture. Opportunities for climate action in agricultural systems (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). CCAFS Info Note. Copenhagen, Denmark: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).

- ^ IPCC. 2007. Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contributions of Working Groups I, Ii, and Iiito the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva: IPCC

- ^ Basak R. 2016. Benefits and costs of climate change mitigation technologies in paddy rice: Focus on Bangladesh and Vietnam. CCAFS Working Paper no. 160. Copenhagen, Denmark: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). https://cgspace.cgiar.org/rest/bitstreams/79059/retrieve (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Wernick, Adam. Climate change is the overlooked driver of Central American migration. The World (Podcast). 2019-02-06 [2021-05-31]. (原始内容存档于2019-02-07).

- ^ 60.0 60.1 Green, Lisa; Schmook, Birgit; Radel, Claudia; Mardero, Sofia. Living Smallholder Vulnerability: The Everyday Experience of Climate Change in Calakmul, Mexico. Journal of Latin American Geography (University of Texas Press). March 2020, 19 (2): 110–142 [2023-11-20]. S2CID 216383920. doi:10.1353/lag.2020.0028. (原始内容存档于2022-06-18).

- ^ {{Cite magazine |last=Blitzer |first=Jonathan |date=2019-04-03 |title=How Climate Change is Fuelling the U.S. Border Crisis |magazine=The New Yorker |url=https://www.newyorker.com/news/dispatch/how-climate-change-is-fuelling-the-us-border-crisis (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) |access-date=2021}-06-01}

- ^ Food for the Future - Assessments of Impacts of Climate Change on Agriculture (新闻稿). Imperial College Press. April 2015 [2019-07-17]. (原始内容存档于2022-04-07).

- ^ Hoffner, Erik. Grand African Savannah Green Up': Major $85 Million Project Announced to Scale up Agroforestry in Africa. Ecowatch. 2019-10-25 [2019-10-27]. (原始内容存档于2019-10-27).

- ^ Climate-Smart Agriculture. World Bank. [2019-07-26]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-03).

- ^ Climate-Smart Agriculture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2019-06-19 [2019-07-26]. (原始内容存档于2022-05-04).

- ^ Das, Sharmistha; Chatterjee, Soumendu; Rajbanshi, Joy. Responses of soil organic carbon to conservation practices including climate-smart agriculture in tropical and subtropical regions: A meta-analysis. Science of the Total Environment. 2022-01-20, 805: 150428. Bibcode:2022ScTEn.805o0428D. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 34818818. S2CID 240584637. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150428.

- ^ Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). What is Climate Smart Agriculture? (PDF). [2022-06-04]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-01-19).

- ^ Gupta, Debaditya; Gujre, Nihal; Singha, Siddhartha; Mitra, Sudip. Role of existing and emerging technologies in advancing climate-smart agriculture through modeling: A review. Ecological Informatics. 2022-11-01, 71: 101805. ISSN 1574-9541. S2CID 252148026. doi:10.1016/j.ecoinf.2022.101805.

- ^ Lipper, Leslie; McCarthy, Nancy; Zilberman, David; Asfaw, Solomon; Branca, Giacomo. Climate Smart Agriculture Building Resilience to Climate Change. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. 2018: 13. ISBN 978-3-319-61193-8 (英语).

- ^ Climate-Smart Agriculture Policies and planning. (原始内容存档于2016-03-31).

外部链接

[编辑]- Climate change (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) on the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations website.

- Report on the relationship between climate change, agriculture and food security (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) by the International Food Policy Research Institute

- Climate Change, Rice and Asian Agriculture: 12 Things to Know (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Asian Development Bank