真菌毒素

真菌毒素(Mycotoxin)又称霉菌毒素,泛指由真菌合成、对人类或其他动物有毒的次级代谢物[1][2][3][4],例如黄曲毒素、橘霉素、伏马镰孢毒素、赭麹毒素、展青霉素、呕吐毒素、玉米赤霉烯酮与麦角菌素等[3]。一种真菌可能分泌多种不同的真菌毒素,不同真菌也可能分泌同种真菌毒素[5]。真菌毒素的讨论范畴通常限于感染农作物的植物病原真菌(主要为霉菌)所分泌的毒素,而不包括有毒蕈类的毒素[3][6]。由真菌产生、对细菌有害的物质则称为抗生素,一般也不列入真菌毒素范畴[3]。

真菌毒素一般非真菌生长所必需[7],可能抑制周围的易感菌种生长,从而有利于产生毒素的真菌。真菌毒素的产生受许多内源与环境因子的影响[8],可造成急性或慢性中毒[9],症状因摄取浓度、时间长度、饮食习惯与基因背景等诸多因素而异[3]。

研究历史

[编辑]真菌毒素(mycotoxin)一词于1962年出现,用于描述当时英国伦敦郊区约十万只火鸡因饲料中的花生带有黄曲毒素而中毒死亡的疫情。1960年至1975年间真菌毒素的相关研究蓬勃发展,约有300多种新的真菌毒素被发现[3]。

主要种类

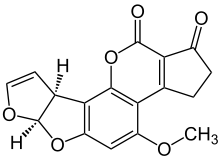

[编辑]黄曲毒素为黄曲霉与寄生曲霉等曲霉属真菌合成的毒素[10][11],包括B1、B2、G1与G2四种[12],其中毒性最高的黄曲毒素B1为致癌物质,污染花生与其他谷物后经食用可能导致肝癌[12]。美国农业部指黄曲毒素可能是被研究、了解最多的真菌毒素[13]。

橘霉素最早自桔青霉发现,现已知数种青霉属与曲霉属真菌皆可合成,其中有些真菌被用于制造起司、味噌与酱油等食物。此毒素可能是造成日本黄变米的毒素之一[14]。橘霉素对许多动物有肾毒性,但对人类的毒性仍尚未完全了解[3]。

赭麹毒素亦由青霉属与曲霉属真菌合成,麹菌感染水果后,可污染酒类、果汁等水果制品。赭麹毒素A有肾毒性,并可能为致癌物质[15]。

麦角毒素泛指麦角菌属真菌的菌核(即麦角)中的生物碱,污染小麦后制成的面包可导致人类与其他动物麦角中毒(圣安东尼之火)。有些麦角生物碱现被用为药物[3]。

生物武器

[编辑]

真菌毒素有用作生物武器的潜力。有证据显示1980年代伊拉克试图将黄曲毒素用作生物武器,大量培养黄曲霉与寄生曲霉以生产上千升的高浓度黄曲毒素。此毒素一般为导致慢性中毒,在战场上不能直接杀伤敌人,但针对少数族裔使用时可能收强力的心理战之效[16][3]。

1981年的黄雨事件中,美国国务卿亚历山大·海格指控苏联向越南、寮国与柬埔寨等东南亚的共产政权提供可造成急性中毒的T-2毒素(一种单端孢霉烯),经飞机与直升机向苗族蒙人的村落喷洒,形成“黄雨”[17]。事后美国生物学家马修·梅瑟生领导的团队前往寮国调查,发现当地植株上的黄色液体实为蜜蜂的粪便,成分主要为花粉[3][18]。

参考文献

[编辑]- ^ Richard JL. Some major mycotoxins and their mycotoxicoses – an overview. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 119 (1–2): 3–10. PMID 17719115. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.07.019.

- ^ Çimen, Duygu; Bereli, Nilay; Denizli, Adil. Patulin Imprinted Nanoparticles Decorated Surface Plasmon Resonance Chips for Patulin Detection. Photonic Sensors. 2022-06-01, 12 (2): 117–129. Bibcode:2022PhSen..12..117C. ISSN 2190-7439. S2CID 239220993. doi:10.1007/s13320-021-0638-1

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 Bennett, J. W.; Klich, M. Mycotoxins. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2003, 16 (3): 497–516. PMC 164220

. PMID 12857779. doi:10.1128/CMR.16.3.497-516.2003.

. PMID 12857779. doi:10.1128/CMR.16.3.497-516.2003.

- ^ Food safety. www.who.int. [2023-09-12]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-11).

- ^ Robbins CA, Swenson LJ, Nealley ML, Gots RE, Kelman BJ. Health effects of mycotoxins in indoor air: a critical review. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2000, 15 (10): 773–84. PMID 11036728. doi:10.1080/10473220050129419.

- ^ Turner NW, Subrahmanyam S, Piletsky SA. Analytical methods for determination of mycotoxins: a review. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2009, 632 (2): 168–80. PMID 19110091. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2008.11.010.

- ^ Fox EM, Howlett BJ. Secondary metabolism: regulation and role in fungal biology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008, 11 (6): 481–87. PMID 18973828. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2008.10.007.

- ^ Hussein HS, Brasel JM. Toxicity, metabolism, and impact of mycotoxins on humans and animals. Toxicology. 2001, 167 (2): 101–34. PMID 11567776. doi:10.1016/S0300-483X(01)00471-1.

- ^ Boonen J, Malysheva S, Taevernier L, Diana Di Mavungu J, De Saeger S, De Spiegeleer B. Human skin penetration of selected model mycotoxins. Toxicology. 2012, 301 (1–3): 21–32. PMID 22749975. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2012.06.012.

- ^ Martins ML, Martins HM, Bernardo F. Aflatoxins in spices marketed in Portugal. Food Addit. Contam. 2001, 18 (4): 315–19. PMID 11339266. S2CID 30636872. doi:10.1080/02652030120041.

- ^ Zain, Mohamed E. Impact of mycotoxins on humans and animals. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society. 2011-04-01, 15 (2): 129–144. ISSN 1319-6103. doi:10.1016/j.jscs.2010.06.006

.

.

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Yin YN, Yan LY, Jiang JH, Ma ZH. Biological control of aflatoxin contamination of crops. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2008, 9 (10): 787–92. PMC 2565741

. PMID 18837105. doi:10.1631/jzus.B0860003.

. PMID 18837105. doi:10.1631/jzus.B0860003.

- ^ Molds on Food: Are They Dangerous?. US Department of Agriculture. [2024-03-31]. (原始内容存档于2024-10-05).

- ^ Xu, Bao-jun; Jia, Xiao-qin; Gu, Li-juan; Sung, Chang-keun. Review on the qualitative and quantitative analysis of the mycotoxin citrinin. Food Control. 2006, 17 (4): 271–285. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2004.10.012.

- ^ Mateo R, Medina A, Mateo EM, Mateo F, Jiménez M. An overview of ochratoxin A in beer and wine. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 119 (1–2): 79–83. PMID 17716764. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.07.029.

- ^ Stone, Richard. Peering Into the Shadows: Iraq's Bioweapons Program. Science. 2002-08-16, 297 (5584): 1110–1112. doi:10.1126/science.297.5584.1110.

- ^ Jonathan Tucker. The Yellow Rain Controversy: Lessons for Arms Control Compliance (PDF). The Nonproliferation Review. Spring 2001 [2024-04-01]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2011-07-20).

- ^ Yellow Rain Falls. New York Times. 1987-09-03 [2009-01-02]. (原始内容存档于2012-11-09).