菲律賓裔美國人

| 菲律賓裔美國人 Filipino Americans Mga Pilipinong Amerikano | |

|---|---|

| |

| 總人口 | |

| 菲律賓裔美國人人口統計 截至2010年超過400萬人[1] | |

| 分佈地區 | |

| 1,474,707人[2] | |

| 342,095人[3] | |

| 139,090人[4] | |

| 137,713人[5] | |

| 137,083人[6] | |

| 126,793人[7] | |

| 126,129人[8] | |

| 123,891人[9] | |

| 122,691人[10] | |

| 語言 | |

| 英語(美國英語、菲律賓英語)[11] 他加祿語 (菲律賓語)[11][12] 伊洛卡諾語、邦阿西楠語、邦板牙語、比科爾語、米沙鄢語(宿霧語、希利蓋農語、瓦瑞語、查瓦卡諾語)與其他菲律賓語言 日語、[11]菲律賓西班牙語、漢語(咱人話、菲律賓華語)(華裔菲律賓人)[13] | |

| 宗教信仰 | |

| 天主教、新教、佛教、無宗教 | |

| 相關族群 | |

| 海外菲律賓人 | |

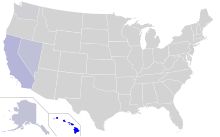

菲律賓裔美國人(英語:Filipino Americans,菲律賓語:Mga Pilipinong Amerikano)為祖先來自菲律賓的美國人,簡稱Fil-Am,部分人自稱皮諾伊,其歷史可追溯至16世紀[14],18世紀起美國開始出現菲律賓裔的聚落[15],1898年美西戰爭後西班牙與美國簽訂巴黎條約,將菲律賓割讓給美國後始有大量菲律賓人移民美國[16][17]。截至2018年,菲律賓裔美國人有約410萬人,在加利福尼亞州、夏威夷州、伊利諾州、德克薩斯州與紐約都會區均有大型聚落[18]。

背景

[編輯]

菲律賓水手為最早航行至美洲的亞洲人[19],早在1587年在今加利福尼亞州的莫羅貝即有菲律賓人出現的紀錄[20]。18世紀始有菲律賓裔的小型聚落[21],1763年西班牙治下的路易斯安那出現了第一個菲律賓人的長期聚落[22],在當地被稱為「馬尼拉人」(Manilamen),曾參加1812年戰爭末期的紐奧良戰役[23]。19世紀開始有菲律賓人在牧場工作[24]。1898年美西戰爭後西班牙與美國簽訂巴黎條約,將菲律賓割讓給美國後始有大量菲律賓人移民美國,1904年在聖路易舉辦的世界博覽會中即有展出菲律賓人[25][26]。1920年代又有許多菲律賓的非技術勞工為尋求工作機會而移民美國[27]。

1930年代菲律賓裔的移民潮一度下降,1946年菲律賓獨立後,移民至美國的菲律賓人持續增加[28],《1965年美國移民和國籍法案》後移民的菲律賓人大多為專業人士與技術工人[27]。2010年美國人口普查結果顯示全國有約340萬名菲律賓裔美國人[29],2011年美國國務院估計其人數應為400萬左右,約合美國人口的1.1%[30],是亞裔美國人中人數次多的,僅次於華裔美國人[31][32],也是海外菲律賓人中人數最多者[33]。

文化

[編輯]菲律賓裔美國人的文化包括西方與東方的許多元素[34],他們會組成社群團體以維繫家庭般的歸屬感,此為菲律賓文化的特色之一[35],加州與夏威夷等菲裔較集中的地區有較緊密的社群[36],有些社群形成了菲裔住宅、商店集中的街區「小馬尼拉」[37],如洛杉磯的舊菲律賓城、舊金山的馬尼拉城[38]、戴利城(約四成人口為菲裔[39])與周邊城鎮、聖地牙哥的納雄耐爾城(約兩成人口為菲裔)[40]、紐約皇后區的伍德賽德(約15%人口為菲裔)[41]、紐澤西州的伯根菲爾德(約兩成人口為菲裔)[42]、夏威夷歐胡島的懷帕胡(超過一半人口為菲裔[43],建有菲律賓社區中心[44])等。

菲律賓裔美國人雖來自亞洲,但因曾為西班牙殖民地,有時也被視為(或自我認同為)拉丁裔[45][46],不過2017年的一項調查顯示僅有約1%的菲律賓裔美國人自認為「西裔」[47]。

語言

[編輯]

因菲律賓曾為美國統治,英語為菲律賓的官方語言之一,多數菲律賓人可流利使用英語[48][49],1990年的亞裔美國人中,菲律賓裔為語言隔閡最小的族群[50]。2003年菲律賓主要的語言他加祿語為美國使用人數排行第五的語言,共有126.2萬人使用[12],2011年已躍升為排行第四的語言[51],加州許多公告、文件都有他加祿語的版本[52],有些中學和大學也設有他加祿語課程[53]。其他菲律賓語言中,伊洛卡諾語為夏威夷除英文外使用人數第三多的語言,僅次於日語和他加祿語[54],也有些菲律賓裔家庭中使用宿霧語[55]、邦阿西楠語、希利蓋農語、邦板牙語、比科爾語與瓦瑞語[56],不過第二代、第三代的菲裔美國人常會失去菲律賓語言能力[57]。另外還有些華裔菲律賓人,移民後成為華裔美國人,使用漢語(咱人話)或西班牙語[13]。

宗教

[編輯]

菲律賓裔天主教徒初到美國時常難以融入本地的天主教會[59][60],而建立了許多自己的天主教會[59][61],如洛杉磯的聖高隆邦菲律賓教堂(St. Columban Filipino Church)[62]與紐約的聖李樂倫小堂(得名自菲律賓第一位被封聖的聖徒李樂倫)[63]。1997年聖母無玷始胎國家朝聖地聖殿中設立了菲裔的禮拜堂[64]。

2010年菲律賓裔天主教徒為美國亞裔天主教徒中最大的群體,占超過75%[65]。2015年65%的菲律賓裔美國人自認為天主教徒(2004年則為68%[66])[67],第一代移民比在美國出生者更常參加彌撒[68]。

飲食

[編輯]

相較於菲律賓裔的人口比例,美國的菲律賓餐館並不多[69][70][71],餐館不是菲裔族群主要的經濟來源[72],即使在菲裔比例相當高的夏威夷歐胡島,菲律賓料理都不如其他亞洲料理普遍[73],有一項研究顯示菲律賓料理很少被列在食物頻率問卷中[74]。菲律賓料理不普及的可能原因包括殖民化心態[71]、定位不明確[71]、菲裔較習慣在家自煮或偏好其他類型的飲食等[70][75],不過菲律賓料理仍流行於菲裔族群間[76],有些為菲裔美國人設立的餐館和雜貨點,如知名的菲律賓速食餐館快樂蜂[69][77][78]。

2010年代起菲律賓餐館逐漸成長。2016年美食雜誌《Bon Appétit》將華盛頓特區的菲律賓餐館Bad Saint評為全美國第二名的新餐館[79],2018年《Food & Wine》雜誌將洛杉磯的菲律賓餐館Lasa列為年度最佳餐館之一[80],美食評論家安德魯·席莫認為菲律賓料理將成為美國料理的「下一波熱潮」(the next big thing)[81]。不過2017年《時尚 (Vogue)》雜誌曾形容菲律賓料理常被誤解與忽略[82],2019年《SF Weekly》雜誌形容菲律賓料理非主流、常被忽視、流行程度起伏不定[83]。

政治

[編輯]

菲律賓裔美國人(特別是隨第二波移民潮落腳美國者[84])傳統上為政治保守派[85],2004年美國總統選舉中投給喬治·沃克·布希者接近投給民主黨候選人約翰·福布斯·凱瑞者的兩倍[86],但2008年投給巴拉克·歐巴馬者有50%至58%,僅有42%至46%投給共和黨候選人約翰·馬侃[87][88],是菲律賓裔美國人首次在總統大選中偏向支持民主黨提名的候選人[89]。

因菲律賓裔美國人社群分散,菲裔候選人難以僅靠此族群的選票當選[90]。首位當選公職的菲裔美國人為彼得·阿杜加,於1954年當選夏威夷州眾議院議員[91]。近年來菲律賓裔參政人數逐漸增加,本·卡耶塔諾(民主黨籍)於1994年至2002年擔任夏威夷州州長,是首位擔任州長的菲裔美國人[92];內華達州參議員約翰·恩賽(共和黨籍)有八分之一的菲律賓血統;曾任俄亥俄州眾議員的史提夫·奧地利(共和黨籍)和加州眾議員T·J·考克斯(民主黨籍)也是菲裔美國人,均有一半菲律賓血統[93]。

參考文獻

[編輯]- ^ U.S. Relations With the Philippines. state.gov. 2020-01-21 [2020-04-04]. (原始內容存檔於2019-05-13).

There more than four million U.S. citizens of Philippine ancestry in the United States

- ^ California. Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010. United States Census Bureau. 2010 [2014-12-07]. (原始內容存檔於2020-02-12).

- ^ Hawaii. Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010. United States Census Bureau. 2010 [2014-12-05]. (原始內容存檔於2020-02-12).

- ^ Illinois. Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010. United States Census Bureau. 2010 [2014-12-05]. (原始內容存檔於2020-02-12).

- ^ Texas. Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010. United States Census Bureau. 2010 [2014-12-05]. (原始內容存檔於2020-02-12).

- ^ Washington. Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010. United States Census Bureau. 2010 [2014-12-05]. (原始內容存檔於2020-02-12).

- ^ New Jersey. Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010. United States Census Bureau. 2010 [2014-12-05]. (原始內容存檔於2020-02-12).

- ^ New York. Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010. United States Census Bureau. 2010 [2014-12-05]. (原始內容存檔於2020-02-12).

- ^ Nevada. Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010. United States Census Bureau. 2010 [2014-12-05]. (原始內容存檔於2020-02-12).

- ^ Florida. Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010. United States Census Bureau. 2010 [2014-12-05]. (原始內容存檔於2020-02-12).

- ^ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Melen McBride. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE OF FILIPINO AMERICAN ELDERS. Stanford University School of Medicine. 史丹佛大學. [2011-06-08]. (原始內容存檔於2011-10-22).

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Statistical Abstract of the United States: page 47: Table 47: Languages Spoken at Home by Language: 2003 (PDF). United States Census Bureau. [2006-07-11]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2010-07-05).

- ^ 13.0 13.1 Jonathan H. X. Lee; Kathleen M. Nadeau. Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife. ABC-CLIO. 2011: 333–334 [2017-04-25]. ISBN 978-0-313-35066-5. (原始內容存檔於2017-04-25).

- ^ Mercene, Floro L. Manila Men in the New World: Filipino Migration to Mexico and the Americas from the Sixteenth Century. The University of the Philippines Press. 2007: 161 [2009-07-01]. ISBN 978-971-542-529-2. (原始內容存檔於2014-05-02).

Rodis 2006 - ^ Rodel Rodis. A century of Filipinos in America. Inquirer. 2006-10-25 [2011-05-04]. (原始內容存檔於2011-05-22).

- ^ Labor Migration in Hawaii. UH Office of Multicultural Student Services. University of Hawaii. [2009-05-11]. (原始內容存檔於2009-06-03).

- ^ Treaty of Paris ends Spanish–American War. History.com. A&E Television Networks, LLC. [2017-03-15]. (原始內容存檔於2017-05-12).

Puerto Rico and Guam were ceded to the United States, the Philippines were bought for $20 million, and Cuba became a U.S. protectorate.

Rodolfo Severino. Where in the World is the Philippines?: Debating Its National Territory. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 2011: 10 [2017-03-16]. ISBN 978-981-4311-71-7. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-16).

Muhammad Munawwar. Ocean States: Archipelagic Regimes in the Law of the Sea. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. 1995-02-23: 62–63 [2017-03-16]. ISBN 978-0-7923-2882-7. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-16).

Thomas Leonard; Jurgen Buchenau; Kyle Longley; Graeme Mount. Encyclopedia of U.S. - Latin American Relations. SAGE Publications. 2012-01-30: 732 [2017-03-16]. ISBN 978-1-60871-792-7. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-16). - ^ Bureau, INQUIRER NET U. S. Filipino population in U.S. now nearly 4.1 million -- new Census data. INQUIRER.net USA. 2019-11-15 [2020-04-04]. (原始內容存檔於2019-12-23).

- ^ Loni Ding. Part 1. COOLIES, SAILORS AND SETTLERS. NAATA. PBS. 2001 [2011-08-20]. (原始內容存檔於2012-05-16).

Most people think of Asians as recent immigrants to the Americas, but the first Asians—Filipino sailors—settled in the bayous of Louisiana a decade before the Revolutionary War.

- ^ Bonus, Rick. Locating Filipino Americans: Ethnicity and the Cultural Politics of Space. Temple University Press. 2000: 191 [2017-05-19]. ISBN 978-1-56639-779-7. (原始內容存檔於2021-01-26).

Historic Site. Michael L. Baird. [2009-04-05]. (原始內容存檔於2011-06-24). - ^ Loni Ding. Part 1. COOLIES, SAILORS AND SETTLERS. NAATA. PBS. 2001 [2011-05-19]. (原始內容存檔於2012-05-16).

Some of the Filipinos who left their ships in Mexico ultimately found their way to the bayous of Louisiana, where they settled in the 1760s. The film shows the remains of Filipino shrimping villages in Louisiana, where, eight to ten generations later, their descendants still reside, making them the oldest continuous settlement of Asians in America.

Loni Ding. 1763 FILIPINOS IN LOUISIANA. NAATA. PBS. 2001 [2011-05-19]. (原始內容存檔於2012-03-21).These are the "Louisiana Manila men" with presence recorded as early as 1763.

Ohamura, Jonathan. Imagining the Filipino American Diaspora: Transnational Relations, Identities, and Communities. Studies in Asian Americans Series. Taylor & Francis. 1998: 36 [2012-09-30]. ISBN 978-0-8153-3183-4. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26). - ^ Eloisa Gomez Borah. Chronology of Filipinos in America Pre-1989 (PDF). Anderson School of Management. University of California, Los Angeles. 1997 [2012-02-25]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2012-02-08).

- ^ Williams, Rudi. DoD's Personnel Chief Gives Asian-Pacific American History Lesson. American Forces Press Service (U.S. Department of Defense). 2005-06-03 [2009-08-26]. (原始內容存檔於2007-06-15).

- ^ Ranching. National Geographic. [2020-05-23]. (原始內容存檔於2020-04-15).

- ^ Jim Zwick. Remembering St. Louis, 1904: A World on Display and Bontoc Eulogy. Syracuse University. 1996-03-04 [2007-05-25]. (原始內容存檔於2007-06-10).

- ^ The Passions of Suzie Wong Revisited, by Rev. Sequoyah Ade. Aboriginal Intelligence. 2004-01-04. (原始內容存檔於2007-09-28).

- ^ 27.0 27.1 Filipino-Americans in the U.S.. Filipino-American Community of South Puget Sound. 2018 [2018-04-16]. (原始內容存檔於2018-02-04).

- ^ Introduction, Filipino Settlements in the United States (PDF). Filipino American Lives. Temple University Press. March 1995 [2009-04-19]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2014-11-28).

- ^ Introduction, Filipino Settlements in the United States (PDF). Filipino American Lives. Temple University Press. 1995 [2014-12-22]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2014-11-28).

- ^ Background Note: Philippines. Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs. United States Department of State. 2011-01-31 [2014-12-22]. (原始內容存檔於2017-01-22).

There are an estimated four million Americans of Philippine ancestry in the United States, and more than 300,000 American citizens in the Philippines.

- ^ Race Reporting for the Asian Population by Selected Categories: 2010. U.S. Census Bureau. [2012-01-17]. (原始內容存檔於2016-10-12).

- ^ Public Information Office. Census Bureau Statement on Classifying Filipinos. United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. 2015-11-09 [2017-03-16]. (原始內容存檔於2017-05-26).

Joan L. Holup; Nancy Press; William M. Vollmer; Emily L. Harris; Thomas M. Vogt; Chuhe Chen. Performance of the U.S. Office of Management and Budget's Revised Race and Ethnicity Categories in Asian Populations. International Journal Intercultural Relations. 2007, 31 (5): 561–573. PMC 2084211 . PMID 18037976. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2007.02.001.

. PMID 18037976. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2007.02.001.

- ^ Jonathan Y. Okamura. Imagining the Filipino American Diaspora: Transnational Relations, Identities, and Communities. Routledge. 2013-01-11: 101 [2017-03-17]. ISBN 978-1-136-53071-5. (原始內容存檔於2021-01-26).

- ^ Yengoyan, Aram A. Christianity and Austronesian Transformations: Church, Polity, and Culture in the Philippines and the Pacific. Bellwood, Peter; Fox, James J.; Tryon, Darrell (編). The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Comparative Austronesian Series. Australian National University E Press. 2006: 360. ISBN 978-1-920942-85-4.

Abinales, Patricio N.; Amoroso, Donna J. State And Society In The Philippines. State and Society in East Asia Series. Rowman & Littlefield. 2005: 158 [2019-01-30]. ISBN 978-0-7425-1024-1. (原始內容存檔於2021-01-26).

Natale, Samuel M.; Rothschild, Brian M.; Rothschield, Brian N. Work Values: Education, Organization, and Religious Concerns. Volume 28 of Value inquiry book series. Rodopi. 1995: 133 [2019-01-30]. ISBN 978-90-5183-880-0. (原始內容存檔於2021-01-26).

Munoz, J. Mark; Alon, Ilan. Entrepreneurship among Filipino immigrants. Dana, Leo Paul (編). Handbook of Research on Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurship: A Co-evolutionary View on Resource Management. Elgar Original Reference Series. Edward Elgar Publishing. 2007: 259 [2013-04-14]. ISBN 978-1-84720-996-2. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26). - ^ Tyner, James A. Filipinos: The Invisible Ethnic Community. Miyares, Ines M.; Airress, Christopher A. (編). Contemporary Ethnic Geographies in America. G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. Rowman & Littlefield. 2007: 264–266. ISBN 978-0-7425-3772-9.菲律賓裔美國人載於Google圖書

- ^ Guevarra, Jr., Rudy P. "Skid Row": Filipinos, Race and the Social Construction of Space in San Diego (PDF). The Journal of San Diego History. 2008, 54 (1) [2011-04-26]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2012-05-12).

Lagierre, Michel S. The global ethnopolis: Chinatown, Japantown, and Manilatown in American society. New York, New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2000: 199 [2019-01-30]. ISBN 978-0-312-22612-1. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26). - ^ Sterngass, Jon. Filipino Americans. New York, New York: Infobase Publishing. 2006: 144 [2019-01-30]. ISBN 978-0-7910-8791-6. (原始內容存檔於2021-01-26).

- ^ Harrell, Ashley. The International Hotel. New York Times. 2011-04-30 [2018-04-25]. (原始內容存檔於2018-04-26).

Franko, Kantele. I-Hotel, 30 years later - Manilatown legacy honored. San Francisco Chronicle. 2007-08-04 [2018-04-25]. (原始內容存檔於2018-04-26). - ^ Pinoy Capital: The Filipino Nation in Daly City 網際網路檔案館的存檔,存檔日期2010-10-24..

- ^ California Filipino Population Percentage City Rank Based on US Census 2010 data. USA.com. [2017-02-13]. (原始內容存檔於2016-01-08).

- ^ JOLLIBEE Brings the Buzz to Queens (PDF). SANLAHI. June 2009 [2014-12-26]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2014-12-27).

- ^ DP-1 - Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data for Bergenfield borough, Bergen County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 16, 2012.

- ^ U.S. Census website. United States Census Bureau. [2008-01-31]. (原始內容存檔於2021-07-09).

- ^ FilipinosInHawaii100.Org -. [2017-02-13]. (原始內容存檔於2017-06-15).

- ^ The Latinos of Asia: How Filipino Americans Break the Rules of Race. Stanford University Press. 2016: 72 [2019-01-30]. ISBN 978-0-8047-9757-3. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26).

- ^ Kevin R. Johnson. Mixed Race America and the Law: A Reader. NYU Press. 2003: 226–227 [2017-03-17]. ISBN 978-0-8147-4256-3. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-17).

Yen Le Espiritu. Asian American Panethnicity: Bridging Institutions and Identities. Temple University Press. 1993-02-11: 172 [2017-03-17]. ISBN 978-1-56639-096-5. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-17). - ^ Jeffrey S. Passel; Paul Taylor. Who's Hispanic?. Hispanic Trends. Pew Research Center. 2009-05-29 [2017-03-15]. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-04).

In the 1980 Census, about one in six Brazilian immigrants and one in eight Portuguese and Filipino immigrants identified as Hispanic. Similar shares did so in the 1990 Census, but by 2000, the shares identifying as Hispanic dropped to levels close to those seen today.

Westbrook, Laura. Mabuhay Pilipino! (Long Life!): Filipino Culture in Southeast Louisiana. Louisiana Folklife Program. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation & Tourism. 2008 [2017-03-16]. (原始內容存檔於2018-05-18). - ^ Fong, Rowena. Culturally competent practice with immigrant and refugee children and families. Guilford Press. 2004: 70 [2009-05-14]. ISBN 978-1-57230-931-9. (原始內容存檔於2009-07-28).

Andres, Tomas Quintin D. People empowerment by Filipino values. Rex Bookstore, Inc. 1998: 17 [2009-05-14]. ISBN 978-971-23-2410-9. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26).

Pinches, Michael. Culture and Privilege in Capitalist Asia. Routledge. 1999: 298. ISBN 978-0-415-19764-9.菲律賓裔美國人載於Google圖書

Roces, Alfredo; Grace Roces. Culture Shock!: Philippines. Graphic Arts Center Pub. Co. 1992. ISBN 978-1-55868-089-0. 菲律賓裔美國人載於Google圖書 - ^ J. Nicole Stevens. The History of the Filipino Languages. Linguistics 450. Brigham Young University. 1999-06-30 [2017-03-16]. (原始內容存檔於2017-05-02).

The Americans began English as the official language of the Philippines. There were many reasons given for this change. Spanish was still not known by very many of the native people. As well, when Taft’s commission (which had been established to continue setting up the government in the Philippines) asked the native people what language they wanted, they asked for English (Frei, 33).

Stephen A. Wurm; Peter Mühlhäusler; Darrell T. Tryon. Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas: Vol I: Maps. Vol II: Texts. Walter de Gruyter. 1996-01-01: 272–273 [2017-03-17]. ISBN 978-3-11-081972-4. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-17). - ^ Don T. Nakanishi; James S. Lai. Asian American Politics: Law, Participation, and Policy. Rowman & Littlefield. 2003: 198 [2015-10-16]. ISBN 978-0-7425-1850-6. (原始內容存檔於2016-01-07).

- ^ Ryan, Camille. Language Use in the United States: 2011 (PDF) (報告). United States Census Bureau. August 2013 [2018-05-13]. American Community Survey Reports. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2016-02-05).

- ^ Language Requirements (PDF). Secretary of State. State of California. [2011-04-30]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2011-09-29).

- ^ Malabonga, Valerie. (2019). Heritage Voices: Programs - Tagalog 網際網路檔案館的存檔,存檔日期2011-09-28..

Blancaflor, Saleah; Escobar, Allyson. Filipino cultural schools help bridge Filipino Americans and their heritage. NBC News. 2018-10-30 [2019-03-02]. (原始內容存檔於2019-03-02). - ^ Nucum, Jun. So what if Tagalog is 3rd most spoken language in 3 US states?. Philippine Daily Inquirer. 2017-08-02 [2018-05-13]. (原始內容存檔於2018-05-14).

- ^ Ilokano Language & Literature Program. Communications department. University of Hawaii at Manao. 2008 [2011-05-01]. (原始內容存檔於2011-09-26).

- ^ Joyce Newman Giger. Transcultural Nursing: Assessment and Intervention. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2014-04-14: 407 [2015-10-16]. ISBN 978-0-323-29328-0. (原始內容存檔於2016-01-07).

- ^ Potowski, Kim. Language Diversity in the USA. Cambridge University Press. 2010: 106 [2012-07-24]. ISBN 978-0-521-76852-8. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26).

Ruether, Rosemary Radford (編). Gender, Ethnicity, and Religion: Views from the Other Side. Fortress Press. 2002: 137 [2012-07-24]. ISBN 978-0-8006-3569-5. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26).

Axel, Joseph. Language in Filipino America (PDF) (學位論文). Arizona State University. January 2011 [2017-04-12]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2017-05-25). - ^ Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths. Pew Research Center. Pew Research Center. 19 July 2012 [28 April 2019]. (原始內容存檔於16 July 2013).

- ^ 59.0 59.1 Laderman, Gary; León, Luís D. Religion and American Cultures: An Encyclopedia of Traditions, Diversity, and Popular Expressions, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. 2003: 28 [2012-07-24]. ISBN 978-1-57607-238-7. (原始內容存檔於2021-01-26).

- ^ Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia. 1901 [2018-04-20]. (原始內容存檔於2020-11-25).

- ^ Thema Bryant-Davis; Asuncion Miteria Austria; Debra M. Kawahara; Diane J. Willis Ph.D. Religion and Spirituality for Diverse Women: Foundations of Strength and Resilience: Foundations of Strength and Resilience. ABC-CLIO. 2014-09-30: 122 [2018-04-20]. ISBN 978-1-4408-3330-4. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26).

- ^ Jonathan H. X. Lee; Kathleen M. Nadeau. Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife. ABC-CLIO. 2011: 357 [2018-04-20]. ISBN 978-0-313-35066-5. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26).

Sucheng Chan. Asian Americans: an interpretive history. Twayne. 1991: 71 [2018-04-20]. ISBN 978-0-8057-8426-8. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26). - ^ Chapel of San Lorenzo Ruiz. Philippine Apostolate / Archdiocese of new York. [2007-08-30]. (原始內容存檔於2008-08-03).

Fr. Diaz. Church of Filipinos opens in New York. The Manila Times. 2005-08-01 [2012-07-24]. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26). - ^ Thomas A. Tweed. America's Church: The National Shrine and Catholic Presence in the Nation's Capital. Oxford University Press. 2011-06-28: 222–224 [2018-04-20]. ISBN 978-0-19-983148-7. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26).

Broadway, Bill. 50-ton Symbol of Unity to Adorn Basilica. Washington Post. 1997-08-02 [2018-04-19]. (原始內容存檔於2018-04-22). - ^ Mark Gray; Mary Gautier; Thomas Gaunt. Cultural Diversity in the Catholic Church in the United States (PDF). United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. June 2014 [2017-03-16]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2017-03-16).

Some 76 percent of Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander Catholics are estimated to self-identify as Filipino (alone and in combinations with other identities).

- ^ Tony Carnes; Fenggang Yang. Asian American Religions: The Making and Remaking of Borders and Boundaries. NYU Press. 2004-05-01: 46 [2018-04-20]. ISBN 978-0-8147-7270-6. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26).

- ^ Lipka, Michael. 5 facts about Catholicism in the Philippines. Fact Tank. Pew Research. 2015-01-09 [2018-04-19]. (原始內容存檔於2015-01-10).

- ^ Stephen M. Cherry. Faith, Family, and Filipino American Community Life. Rutgers University Press. 2014-01-03: 149–150 [2018-04-20]. ISBN 978-0-8135-7085-3. (原始內容存檔於2021-01-26).

- ^ 69.0 69.1 Cowen, Tyler. An Economist Gets Lunch: New Rules for Everyday Foodies. Penguin. 2012: 118 [2012-09-14]. ISBN 978-1-101-56166-9. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26).

Yet, according to one source, there are only 481 Filipino restaurants in the country;

- ^ 70.0 70.1 Shaw, Steven A. Asian Dining Rules: Essential Strategies for Eating Out at Japanese, Chinese, Southeast Asian, Korean, and Indian Restaurants. New York, New York: HarperCollins. 2008: 131 [2019-01-30]. ISBN 978-0-06-125559-5. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26).

- ^ 71.0 71.1 71.2 Dennis Clemente. Where is Filipino food in the US marketplace?. Philippine Daily Inquirer. 2010-07-01 [2011-06-21]. (原始內容存檔於2012-03-18).

- ^ Alice L. McLean. Asian American Food Culture. ABC-CLIO. 2015-04-28: 127 [2017-03-20]. ISBN 978-1-56720-690-6. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-21).

- ^ Carpenter, Robert; Carpenter, Robert E.; Carpenter, Cindy V. Oahu Restaurant Guide 2005 With Honolulu and Waikiki. Havana, Illinois: Holiday Publishing Inc. 2005: 20 [2019-01-30]. ISBN 978-1-931752-36-7. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26).

- ^ Johnson-Kozlow, Marilyn; Matt, Georg; Rock, Cheryl; de la Rosa, Ruth; Conway, Terry; Romero, Romina. Assessment of Dietary Intakes of Filipino-Americans: Implications for Food Frequency Questionnaire Design. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2011-06-25, 43 (6): 505–510. PMC 3204150

. PMID 21705276. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2010.09.001.

. PMID 21705276. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2010.09.001.

- ^ Laudan, Rachel. The food of Paradise: exploring Hawaii's culinary heritage. Seattle: University of Hawaii Press. 1996: 152 [2019-01-30]. ISBN 978-0-8248-1778-7. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-26).

- ^ Melanie Henson Narciso. Filipino Meal Patterns in the United States of America (PDF) (學位論文). University of Wisconsin-Stout. 2005 [2012-09-13]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2012-03-26).

- ^ Kristy, Yang. Filipino Food: At Least One Reason to Envy California. Dallas Observer. 2011-07-30 [2012-09-13]. (原始內容存檔於2012-10-10).

- ^ Krean Given. In Southern California, Filipino restaurants crowd the strip malls. Boston Globe. 2012-11-13 [2013-04-09]. (原始內容存檔於2012-11-22).

Marc Ballon. Jollibee Struggling to Expand in U.S.. Los Angeles Times. 2002-09-16 [2013-04-09]. (原始內容存檔於2017-04-24).

Berger, Sarah. Why everyone is obsessed with Jollibee fast food — from its sweet spaghetti to fried chicken better than KFC. CNBC (New York). 2019-04-03 [2019-08-14]. (原始內容存檔於2019-08-15). - ^ Knowlton, Andrew. No. 02. Bonappetit.com. 2016-08-16 [2018-01-09]. (原始內容存檔於2018-01-04).

- ^ Rothman, Jordana. Food & Wine Restaurants of the Year 2018. Food & Wine. [2018-04-15]. (原始內容存檔於2018-04-15).

- ^ Kim, Gene; Appolonia, Alexandra. Andrew Zimmern: Filipino food will be the next big thing in America — here's why. Businessinsider.com. 2017-08-16 [2018-01-09]. (原始內容存檔於2018-01-04).

- ^ McNeilly, Claudia. How Filipino Food Is Becoming the Next Great American Cuisine. Vogue. 2017-06-01 [2018-04-20]. (原始內容存檔於2018-04-21).

- ^ Kane, Peter Lawrence. FOB Kitchen Deserves to Become a Filipino Hotspot. SF Weekly. 2019-02-21 [2019-02-23]. (原始內容存檔於2019-02-22).

- ^ Vergara, Benito. Pinoy Capital: The Filipino Nation in Daly City. Asian American History & Culture. Temple University Press. 2009: 111–12. ISBN 978-1-59213-664-3.

- ^ Thomas Chen. WHY ASIAN AMERICANS VOTED FOR OBAMA. PERSPECTIVE MAGAZINE. 2009-02-26 [2013-03-04]. (原始內容存檔於2014-08-26).

A survey of Filipino Americans in California—the second largest Asian American ethnic group and traditionally Republican voters

- ^ Jim Lobe. Asian-Americans lean toward Kerry. Asia Times. 2004-09-16 [2011-03-16]. 原始內容存檔於2008-09-19.

- ^ Gus Mercado. Obama wins Filipino vote at last-hour. Philippine Daily Inquirer. 2008-11-10 [2012-10-22]. (原始內容存檔於2012-02-27).

A pre-election survey of 840 active Filipino community leaders in America showed a strong shift of undecided registered voters towards the Obama camp in the last several weeks before the elections that gave Senator Barack Obama of Illinois a decisive 58–42 share of the Filipino vote.

- ^ Mico Letargo. Fil-Ams lean towards Romney – survey. Asian Journal. 2012-10-19 [2012-10-22]. (原始內容存檔於2012-10-23).

In 2008, 50 percent of the Filipino community voted for President Barack Obama (the Democrat candidate back then) while 46 percent voted for Republican Senator John McCain.

- ^ Thomas Chen. Why Asian Americans Voted for Obama. PERSPECTIVE. Harvard University. 2009-02-26 [2011-03-28]. (原始內容存檔於2010-04-30).

- ^ Reimers, David M. Other Immigrants: The Global Origins of The American People. NYU Press. 2005: 173. ISBN 978-0-8147-7535-6.

- ^ Jon Sterngass. Filipino Americans. Infobase Publishing. 2009-01-01: 128. ISBN 978-1-4381-0711-0.

- ^ Benjamin Cayetano, Governor of Hawaii. UCLA Spotlight. [2012-11-26]. (原始內容存檔於2012-02-27).

- ^ Varona, Rae Ann. Obama endorses Fil-Am TJ Cox for Congress. Asian Journal. 2018-08-05 [2021-06-21]. (原始內容存檔於2020-11-30).

Born in Walnut Creek, California to immigrant parents — his mother Perla De Castro from the Philippines, and half-Chinese father from China — Cox is among several congressional Filipino candidates who advanced to California’s general elections.