用户:Yenhochia/乔治·华盛顿与奴隶制

乔治·华盛顿与奴隶制度的关系,反映著乔治·华盛顿对于蓄奴行为的态度变化。乔治·华盛顿做为一名美国开国元勋和奴隶主,其一生对存在已久的蓄奴制度,态度时常发生转变,而他在死后则将他的奴隶全数释放。

奴隶制度深植在殖民时期的美国经济与社会之中,包括华盛顿的故乡维吉尼亚。1743年,华盛顿11岁时,因为父亲离世的关系而继承了十个奴隶,这是他人生中第一次拥有奴隶。华盛顿成年之后,除了新购入的奴隶以外,他所拥有的奴隶数也因自然增长(奴隶生出的小孩仍为奴隶)而增加。1759年,华盛顿与寡妇马莎·华盛顿成婚后,马莎·华盛顿继承并带来了已逝前夫的奴隶,因此华盛顿除了自己原有的奴隶外,同时也能控制马莎的奴隶。华盛顿早期对奴隶制的态度,与当时多数的维吉尼亚种植园主相同,起初也没有对这种制度产生疑问。约在1760年代美国独立战争发生前,华盛顿将自己的农场从种植烟草改为种植谷物,导致奴工劳力过剩,变相增加了不少成本,也使得他开始怀疑奴隶制度的经济效益。1774年,华盛顿基于道德问题,在费尔法克斯决议中公开谴责贩奴行为。独立战争结束后,华盛顿逐步利用立法来支持废奴。虽然华盛顿的事业还是得仰赖奴隶劳工,但其私底下常常告诉别人自己支持废奴。华盛顿在1799年逝世时,维农山庄中的317名奴隶,其中124名为华盛顿所有,其馀则为他人所有。

华盛顿除了自身具有十分强烈的职业道德观外,还会将之加诸在为他工作的工人和奴隶上。华盛顿会为自己的奴隶提供基本所需的粮食、衣物、医疗保障,和相对其他奴隶主而言较为充足的居住空间。作为回报,他要求奴隶们按照当时的标准,每周六天辛勤地从日出时分工作到日落为止。其中三分之二的奴隶负责在农地工作,其馀的则作为华盛顿的家奴和工匠。奴隶们会利用闲暇时间打猎、诱捕动物,以及种植蔬果来增加食物来源,或是出售他们生产出来的物品和捕获的猎物,以购买食物、衣物以及家用品。奴隶们会因为婚姻和家庭因素建立自己的社区,然而华盛顿并不考虑奴隶们彼此的关系,只按照自己事业上的需求来指派奴隶居住在农场各处,因此许多身为奴隶的父亲们得在工作日时,与自己的妻儿分开生活。华盛顿在管理奴隶时赏罚并用,但又时常因为奴隶们达不到他严苛的标准而感到失望。很多维农山庄的奴隶们会利用各种方法来反抗这个制度,例如通过偷窃来补充自己的衣粮和收入、或是装病和逃跑。

1775年,作为大陆军总司令的华盛顿,在独立战争初期时不允许非裔美国人加入军队取得军衔,不论其是否身为奴隶,但面对战争的需求,华盛顿后来还是得领导一支种族融合的军队。1778年时,华盛顿表示不愿在公开场合出售自己的奴隶,抑或是拆散他们的家庭,这是他第一次对奴隶制度表现出道德上的质疑。独立战争结束之后,华盛顿未能成功要求英国根据和约,无一例外地归还逃跑的奴隶。华盛顿在辞去军队职务的公开声明中,提到多个新邦联所面对的挑战,但其中并没有明显的提到奴隶制度。从政治来说,华盛顿认为美国具有争议的奴隶制度,威胁到了国家的凝聚力,但是他从未在公开场合提到这些。华盛顿曾私底下计画于1790年代中期释放自己所拥有的奴隶,然而因为无法取得必要的资金、家人拒绝释放马莎继承前夫遗产所带来的奴隶,加上他不希望拆散奴隶的家庭,导致他的计划通通无从施行。华盛顿在1799年逝世后,他的遗嘱被广泛的传播,并为他的奴隶带来了自由,而华盛顿是唯一一个释放自己奴隶的美国开国元勋。由于许多华盛顿所拥有的奴隶与马莎继承的奴隶结婚,因此他没办法合法的释放他们,只有华盛顿的奴仆威廉·李立刻获得自由,而其他的奴工必须得到他的妻子马莎去世后,才真正重获自由。马莎在1802年逝世的前一年,便让那些奴隶重获自由,但是其他由孙辈继承的奴隶,她并没有能力去释放他们。

背景

[编辑]

自1619年第一批非洲人被运送至旧康福特角后,为当时属于英国殖民地的维吉尼亚,展开奴隶制度的序幕。信仰基督教的奴隶会变成“基督教仆从”(Christian servants),并在作为奴隶一定时间之后,能够重获自由身,然而这个重获自由的机制,最终也渐渐的被取消了。到了1667年,弗吉尼亚议会通过了一项法案,宣布受洗不具有赋予人自由的功能。如果非洲人在抵达维吉尼亚前便已受洗,将能够取得契约劳工的身分,然而到了1682年,另一项法律将他们通通归类为奴隶。位于维吉尼亚社会底层的白人和非洲人,拥有相似的处境和生活方式,而这两个族群彼此也有通婚的情况,而在1691年,维吉尼亚议会禁止这种结婚行为,而违者可能会遭到流放[1]。

1671年,维吉尼亚的人口数为4万人,其中6千人为白人契约劳工,非洲裔只占2千人,其中三分之一在某些县里属于自由人。随著时间来到17世纪末,英国人开始停止自维吉尼亚输出便宜劳力,改为供维吉尼亚自身所用,当时维吉尼亚契约劳工的来源渐渐枯竭,移民的数量从1680年代的每年1500到2000人,缩减到1715年仅百馀人。而随著烟草种植面积增加,为了填补劳力的空缺,奴隶的数量开始不断增加。透过1705年维吉尼亚奴隶法,种族变成奴隶制度的根本,在自然增长的催化下,奴隶数量在1710年左右开始加速增长。1700年到1750年间,维吉尼亚内的奴隶数量从13,000人,上升到105,000人,其中近80%出生于维吉尼亚[2]。而在华盛顿的一生中,奴隶制度深深的植入了维吉尼亚的社经结构之中[3]。

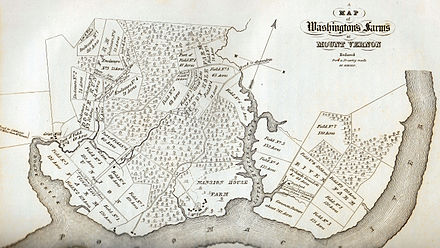

乔治·华盛顿出生于1732年,是其父奥古斯丁在第二段婚姻中的第一个小孩。奥古斯丁是一名拥有面积约10,000英亩(4,000公顷)的烟草种植园主,并拥有50名奴隶。奥古斯丁于1743年过世之后,他将占地2,500英亩(1,000公顷)小猎溪(Little Hunting Creek)种植园交给了华盛顿同父异母的哥哥劳伦斯·华盛顿,而劳伦斯后来将它重新命为维农山庄,至于华盛顿则继承了260英亩(110公顷)大的费里农场和10名奴隶[4]。华盛顿在哥哥死后两年,从哥哥的遗孀租借了维农庄园,尔后在1761年继承该庄园[5]。华盛顿也是一名相当有胆识的土地投机商。他在1774时,已经在维吉尼亚西边的俄亥俄地区拥有面积约32,000英亩(13,000公顷)的土地。等到他去世时,其名下的土地面积已超过80,000英亩(32,000公顷)[6][7][8]。1757年,华盛顿开始有计划地扩张维农山庄,最后在8,000英亩(3,200公顷)的土地上建立一座具有五个农场的庄园,这些最初则被华盛顿用来种植烟草[9][a]。

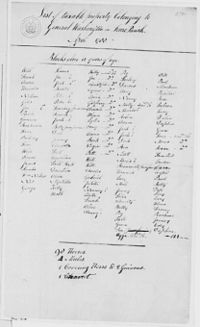

农地必须要有人耕作,而在18世纪的美国南方,人力就代表著奴隶。华盛顿继承了哥哥劳伦斯的奴隶,然后透过租借维农山庄的合约取得了更多奴隶,哥哥的妻子在1761年去世后,哥哥妻子的奴隶也由华盛顿继承[12][13]。华盛顿在1759年与马莎·华盛顿成婚后,华盛顿掌控了马莎继承前夫遗产所获得的奴隶。这些奴隶属于玛莎,而玛莎则为了前夫卡斯蒂斯的继承人,将他们给托管起来,虽然华盛顿在法律上不拥有这些奴隶,他还是把这些奴隶当作自己的财产使唤[14][15][16]。1752年到1773年间,华盛顿至少购买了71名 – 男女和孩童当作奴隶.[17][18]。在美国独立革命后,虽然华盛顿购买奴隶的数量明显减少,但其所拥有的数量仍持续增加,多数是因为奴隶繁衍而增加,偶尔会因为有人用奴隶抵债而获得新的奴隶[19][17]。1786年,华盛顿是费尔法克斯郡其中的一个大奴隶主,他的名单上记有216名奴隶,其中122名为成年男女,88名为儿童[b]。而这些奴隶中,有103名为华盛顿所有,其馀的皆属于妻子。华盛顿在1799年逝世后,维农山庄的奴隶数已经增加到317人,其中143人儿童。在这之中,40名奴隶为华盛顿租借而来、153名不属于华盛顿但为他所用,剩下的124名才是实际隶属华盛顿名下的奴隶[21][22]。

维农山庄的奴隶

[编辑]华盛顿认为自己与手下的工人们,都是大家庭的一部份,而自己是负责当家做主的父亲。他面对自己奴隶的态度,表现出了父权和家长式领导的要素。华盛顿心目中的大家长,必须使人绝对服从、严格掌控著奴隶,还要向他一样在情感上对奴隶们保持距离[23][24]。虽然有像威廉·李受华盛顿真心喜爱的奴隶,但数量寥寥无几[25][26]。华盛顿脑中的家长主义思维,使其将自己和奴隶间的关系,看作是彼此的责任,则华盛顿满足奴隶所需、奴隶负责服侍华盛顿,而奴隶也能像华盛顿表达自己的顾虑和不满[23][27]。家长主义式的奴隶主们认为,慷慨对待奴隶们的自己,应受到奴隶的感激[28]。如1796年,其妻马莎·华盛顿的女奴仆欧妮·贾奇逃跑后,华盛顿便抱怨道:“像自己的孩子般养育她,但她却如此忘恩负义。”[29]

Although Washington employed a farm manager to run the estate and an overseer at each of the farms, he was a hands-on manager who ran his business with a military discipline and involved himself in the minutiae of everyday work.[34][35] During extended absences while on official business, he maintained close control through weekly reports from the farm manager and overseers.[36] He demanded from all of his workers the same meticulous eye for detail that he exercised himself; a former enslaved worker would later recall that the "slaves...did not quite like" Washington, primarily because "he was so exact and so strict...if a rail, a clapboard, or a stone was permitted to remain out of its place, he complained; sometimes in language of severity."[37][38] In Washington's view, "lost labour is never to be regained", and he required "every labourer (male or female) [do] as much in the 24 hours as their strength without endangering the health, or constitution will allow of". He had a strong work ethic and expected the same from his workers, enslaved and hired.[39] He was constantly disappointed with enslaved workers who did not share his motivation and resisted his demands, leading him to regard them as indolent and insist that his overseers supervise them closely at all times.[40][41][42]

In 1799, nearly three-quarters of the enslaved population, over half of them female, worked in the fields. They were kept busy year round, their tasks varying with the season.[43] The remainder worked as domestic servants in the main residence or as artisans, such as carpenters, joiners, coopers, spinners and seamstresses.[44] Between 1766 and 1799, seven dower slaves worked at one time or another as overseers.[45] The enslaved were expected to work from sunrise to sunset over a six-day work week that was standard on Virginia plantations. With two hours off for meals, their workdays would range between seven and a half hours to thirteen hours, depending on season. They were given three or four days off at Christmas and a day each at Easter and Whitsunday.[46] Domestic slaves started early, worked into the evenings and did not necessarily have Sundays and holidays free.[47] On special occasions when enslaved workers were required to put in extra effort, such as working through a holiday or bringing in the harvest, they were paid or compensated with extra time off.[48]

Washington instructed his overseers to treat enslaved people "with humanity and tenderness" when sick.[40] Enslaved people who were less able, through injury, disability or age, were given light duties, while those too sick to work were generally, though not always, excused work while they recovered.[49] Washington provided them with good, sometimes costly medical care – when an enslaved person named Cupid fell ill with pleurisy, Washington had him taken to the main house where he could be better cared for and personally checked on him throughout the day.[41][50] The paternal concern for the welfare of his enslaved workers was mixed with an economic consideration for the lost productivity arising from sickness and death among the labor force.[51][52]

Living conditions

[编辑]

At Mansion House Farm, most of the enslaved people were housed in a two-story frame building known as the "Quarters for Families". This was replaced in 1792 by brick-built accommodation wings either side of the greenhouse comprising four rooms in total, each some 600平方英尺(56平方米). The Mount Vernon Ladies' Association have concluded these rooms were communal areas furnished with bunks that allowed little privacy for the predominantly male occupants. Other enslaved people at Mansion House Farm lived over the outbuildings where they worked or in log cabins.[53] Such cabins were the standard slave accommodation at the outlying farms, comparable to the accommodation occupied by the lower strata of free white society across the Chesapeake area and by the enslaved on other Virginia plantations.[54] They provided a single room that ranged in size from 168平方英尺(15.6平方米) to 246平方英尺(22.9平方米) to house a family.[55] The cabins were often poorly constructed, daubed with mud for draft- and water-proofing, with dirt floors. Some cabins were built as duplexes; some single-unit cabins were small enough to be moved on carts.[56] There are few sources which shed light on living conditions in these cabins, but one visitor in 1798 wrote, "husband and wife sleep on a mean pallet, the children on the ground; a very bad fireplace, some utensils for cooking, but in the middle of this poverty some cups and a teapot". Other sources suggest the interiors were smoky, dirty and dark, with only a shuttered opening for a window and the fireplace for illumination at night.[57]

Washington provided his enslaved people with a blanket each fall at most, which they used for their own bedding and which they were required to use to gather leaves for livestock bedding.[58] Enslaved people at the outlying farms were issued with a basic set of clothing each year, comparable to the clothing issued on other Virginia plantations. The enslaved slept and worked in their clothes, leaving them to spend many months in garments that were worn, ripped and tattered.[59] Domestic slaves at the main residence who came into regular contact with visitors were better clothed; butlers, waiters and body servants were dressed in a livery based on the three-piece suit of an 18th-century gentleman, and maids were provided with finer quality clothing than their counterparts in the fields.[60]

Washington desired his enslaved workers to be fed adequately but no more.[61] Each enslaved person was provided with a basic daily food ration of one美制夸脱(0.95公升) or more of cornmeal, up to eight盎司(230克) of herring and occasionally some meat, a fairly typical ration for the enslaved population in Virginia that was adequate in terms of the calorie requirement for a young man engaged in moderately heavy agricultural labor but nutritionally deficient.[62] The basic ration was supplemented by enslaved people's own efforts hunting (for which some were allowed guns) and trapping game. They grew their own vegetables in small garden plots they were permitted to maintain in their own time, on which they also reared poultry.[63]

Washington often tipped enslaved people on his visits to other estates, and it is likely that his own enslaved workers were similarly rewarded by visitors to Mount Vernon. Enslaved people occasionally earned money through their normal work or for particular services rendered – for example, Washington rewarded three of his own enslaved with cash for good service in 1775, an enslaved person received a fee for the care of a mare that was being bred in 1798 and the chef Hercules profited well by selling slops from the presidential kitchen.[64] Enslaved people also earned money from their own endeavors, by selling to Washington or at the market in Alexandria food they had caught or grown and small items they had made.[65] They used the proceeds to purchase from Washington or the shops in Alexandria better clothing, housewares and extra provisions such as flour, pork, whiskey, tea, coffee and sugar.[66]

Family and community

[编辑]

Although the law did not recognize slave marriages, Washington did, and by 1799 some two-thirds of the enslaved adult population at Mount Vernon were married.[67] To minimize time lost in getting to the workplace and thus increase productivity, enslaved people were accommodated at the farm on which they worked. Because of the unequal distribution of males and females across the five farms, enslaved people often found partners on different farms, and in their day-to-day lives husbands were routinely separated from their wives and children. Washington occasionally rescinded orders so as not to separate spouses, but the historian Henry Wiencek writes, "as a general management practice [Washington] institutionalized an indifference to the stability of enslaved families."[68] Only thirty-six of the ninety-six married slaves at Mount Vernon in 1799 lived together, while thirty-eight had spouses who lived on separate farms and twenty-two had spouses who lived on other plantations.[69] The evidence suggests couples that were separated did not regularly visit during the week, and doing so prompted complaints from Washington that enslaved people were too exhausted to work after such "night walking", leaving Saturday nights, Sundays and holidays as the main time such families could spend together.[70] Despite the stress and anxiety caused by this indifference to family stability – on one occasion an overseer wrote that the separation of families "seems like death to them" – marriage was the foundation on which the enslaved population established their own community, and longevity in these unions was not uncommon.[71][72]

Large families that covered multiple generations, along with their attendant marriages, were part of an enslaved community-building process that transcended ownership. Washington's head carpenter Isaac, for example, lived with his wife Kitty, a dower-slave milkmaid, at Mansion House Farm. The couple had nine daughters ranging in age from six to twenty-seven in 1799, and the marriages of four of those daughters had extended the family to other farms within and outside the Mount Vernon estate and produced three grandchildren.[73][74] Children were born into slavery, their ownership determined by the ownership of their mothers.[75] The value attached to the birth of an enslaved child, if it was noted at all, is indicated in the weekly report of one overseer, which stated, "Increase 9 Lambs & 1 male child of Lynnas." New mothers received a new blanket and three to five weeks of light duties to recover. An infant remained with its mother at her place of work.[76] Older children, the majority of whom lived in single-parent households in which the mother worked from dawn to dusk, performed small family chores but were otherwise left to play largely unsupervised until they reached an age when they could begin to be put to work for Washington, usually somewhere between eleven and fourteen years old.[77] In 1799, nearly sixty percent of the slave population was under nineteen years old and nearly thirty-five percent under nine.[73]

There is evidence that enslaved people passed on their African cultural values through telling stories, among them the tales of Br'er Rabbit which, with their origins in Africa and stories of a powerless individual triumphing through wit and intelligence over powerful authority, would have resonated with the enslaved.[78] African-born slaves brought with them some of the religious rituals of their ancestral home, and there is an undocumented tradition of voodoo being practiced at one of the Mount Vernon farms.[79] Although the slave condition made it impossible to adhere to the Five Pillars of Islam, some slave names betray a Muslim cultural origin.[80] Anglicans reached out to American-born slaves in Virginia, and some of the Mount Vernon enslaved population are known to have been christened before Washington acquired the estate. There is evidence in the historical record from 1797 that the enslaved population at Mount Vernon had contacts with Baptists, Methodists and Quakers.[81] The three religions advocated abolition, raising hopes of freedom among the enslaved, and the congregation of the Alexandria Baptist Church, founded in 1803, included enslaved people formerly owned by Washington.[82]

Mulattoes and interracial sex

[编辑]| 外部视频链接 | |

|---|---|

In 1799 there were some twenty mulatto (mixed race) enslaved people at Mount Vernon. However, there is no credible evidence that George Washington took sexual advantage of any slave.[83][84][c]

The probability of paternal relationships between enslaved and hired white workers is indicated by some surnames: Betty and Tom Davis, probably the children of Thomas Davis, a white weaver at Mount Vernon in the 1760s; George Young, likely the son of a man of the same name who was a clerk at Mount Vernon in 1774; and Judge and her sister Delphy, the daughters of Andrew Judge, an indentured tailor at Mount Vernon in the 1770s and 1780s.[87] There is evidence to suggest that white overseers – working in close proximity to enslaved people under the same demanding master and physically and socially isolated from their own peer group, a situation that drove some to drink – indulged in sexual relations with the enslaved people they supervised.[88] Some white visitors to Mount Vernon seemed to have expected enslaved women to provide sexual favors.[89] The living arrangements left some enslaved females alone and vulnerable, and the Mount Vernon research historian Mary V. Thompson writes that relationships "could have been the result of mutual attraction and affection, very real demonstrations of power and control, or even exercises in the manipulation of an authority figure".[90]

Resistance

[编辑]

Although some of the enslaved population at Mount Vernon came to feel a loyalty toward Washington, the resistance displayed by a significant percentage of them is indicated by the frequent comments Washington made about "rogueries" and "old tricks".[91][92] The most common act of resistance was theft, so common that Washington made allowances for it as part of normal wastage. Food was stolen both to supplement rations and to sell, and Washington believed the selling of tools was another source of income for enslaved people. Because cloth and clothing were commonly stolen, Washington required seamstresses to show the results of their work and the leftover scraps before issuing them with more material. Sheep were washed before shearing to prevent the theft of wool, and storage areas were kept locked and keys left with trusted individuals.[93] In 1792, Washington ordered the culling of enslaved people's dogs he believed were being used in a spate of livestock theft and ruled that enslaved people who kept dogs without authorization were to be "severely punished" and their dogs hanged.[94]

Another means by which enslaved people resisted, one that was virtually impossible to prove, was feigning illness. Over the years Washington became increasingly skeptical about absenteeism due to sickness among his enslaved population and concerned about the diligence or ability of his overseers in recognizing genuine cases. Between 1792 and 1794, while Washington was away from Mount Vernon as President, the number of days lost to sickness increased tenfold compared to 1786, when he was resident at Mount Vernon and able to control the situation personally. In one case, Washington suspected an enslaved person of frequently avoiding work over a period of decades through acts of deliberate self harm.[95]

Enslaved people asserted some independence and frustrated Washington by the pace and quality of their work.[96] In 1760, Washington noted that four of his carpenters quadrupled their output of timber under his personal supervision.[97] Thirty-five years later, he described his carpenters as an "idle...set of rascals" who would take a month or more to complete at Mount Vernon work that was being done in two or three days in Philadelphia. The output of seamstresses dropped off when Martha was away, and spinners found they could slacken by playing the overseers off against her.[98] Tools were regularly lost or damaged, thus stopping work, and Washington despaired of employing innovations that might improve efficiency because he believed enslaved workers were too clumsy to operate the new machinery involved.[99]

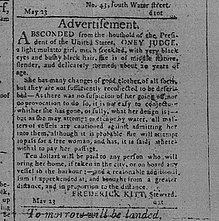

The most emphatic act of resistance was to run away, and between 1760 and 1799 at least forty-seven enslaved people under Washington's control did so.[100] Seventeen of these, fourteen men and three women, escaped to a British warship that anchored in the Potomac River near Mount Vernon in 1781.[101] In general, the best chance of success lay with second- or third-generation African-American enslaved people who had good English, possessed skills that would allow them to support themselves as free people and were in close enough contact with their masters to receive special privileges. Thus it was that Judge, an especially talented seamstress, and Hercules escaped in 1796 and 1797 respectively and eluded recapture.[102] Washington took seriously the recapture of fugitives, and in three cases enslaved people who had escaped were sold off in the West Indies after recapture, effectively a death sentence in the severe conditions the enslaved had to endure there.[103][104][105]

Control

[编辑]Associate Curator

George Washington's Mount Vernon[106]

Washington used both reward and punishment to encourage discipline and productivity in his enslaved population.[107] In one case, he suggested "admonition and advice" would be more effective than "further correction", and he occasionally appealed to an enslaved person's sense of pride to encourage better performance. Rewards in the form of better blankets and clothing fabric were given to the "most deserving", and there are examples of cash payments being awarded for good behavior.[108] He opposed the use of the lash in principle, but saw the practice as a necessary evil and sanctioned its occasional use, generally as a last resort, on enslaved people, both male and female, if they did not, in his words, "do their duty by fair means".[107] There are accounts of carpenters being whipped in 1758 when the overseer "could see a fault", of an enslaved person called Jemmy being whipped for stealing corn and escaping in 1773 and of a seamstress called Charlotte being whipped in 1793 by an overseer "determined to lower Spirit or skin her Back" for impudence and refusing to work.[109][110]

Washington regarded the "passion" with which one of his overseers administered floggings to be counter-productive, and Charlotte's protest that she had not been whipped in fourteen years indicates the frequency with which physical punishment was used.[111][112] Whippings were administered by overseers after review, a system Washington required to ensure enslaved people were spared capricious and extreme punishment. Washington did not himself flog enslaved people, but he did on occasion lash out in a flash of temper with verbal abuse and physical violence when they failed to perform as he expected.[113][d] Contemporaries generally described Washington as having a calm demeanor, but there are several reports from those who knew him privately that mention his temper. One wrote that "in private and particularly with his servants, its violence sometimes broke out". Another reported that Washington's servants "seemed to watch his eye and to anticipate his every wish; hence a look was equivalent to a command".[115] Threats of demotion to fieldwork, corporal punishment and being shipped to the West Indies were part of the system by which he controlled his enslaved population.[103][116]

Evolution of Washington's attitudes

[编辑]

Washington's early views on slavery were no different from any Virginia planter of the time.[51] He demonstrated no moral qualms about the institution, and referred to slaves as "a Species of Property" during those years as he would later in life when he favored abolition.[117] The economics of slavery prompted the first doubts in Washington about the institution, marking the beginning of a slow evolution in his attitude towards it. By 1766, he had transitioned his business from the labor-intensive planting of tobacco to the less demanding farming of grain crops. His slaves were employed on a greater variety of tasks that needed more skills than tobacco planting required of them; as well as the cultivation of grains and vegetables, they were employed in cattle herding, spinning, weaving and carpentry. The transition left Washington with a surplus of slaves and revealed to him the inefficiencies of the slave labor system.[118][119]

There is little evidence that Washington seriously questioned the ethics of slavery before the Revolution.[119] In the 1760s he often participated in tavern lotteries, events in which defaulters' debts were settled by raffling off their assets to a high-spirited crowd.[120] In 1769, Washington co-managed one such lottery in which fifty-five slaves were sold, among them six families and five females with children. The more valuable married males were raffled together with their wives and children; less valuable slaves were separated from their families into different lots. Robin and Bella, for example, were raffled together as husband and wife while their children, twelve-year-old Sukey and seven-year-old Betty, were listed in a separate lot. Only chance dictated whether the family would remain together, and with 1,840 tickets on sale the odds were not good.[121]

| 外部视频链接 | |

|---|---|

The historian Henry Wiencek concludes that the repugnance Washington felt at this cruelty in which he had participated prompted his decision not to break up slave families by sale or purchase, and marks the beginning of a transformation in Washington's thinking about the morality of slavery.[122] Wiencek writes that in 1775 Washington took more slaves than he needed rather than break up the family of a slave he had agreed to accept in payment of a debt.[123] The historians Philip D. Morgan and Peter Henriques[e] are skeptical of Wiencek's conclusion and believe there is no evidence of any change in Washington's moral thinking at this stage. Morgan writes that in 1772, Washington was "all business" and "might have been buying livestock" in purchasing more slaves who were to be, in Washington's words, "strait Limb'd, & in every respect strong & likely, with good Teeth & good Countenance". Morgan gives a different account of the 1775 purchase, writing that Washington resold the slave because of the slave's resistance to being separated from family and that the decision to do so was "no more than the conventional piety of large Virginia planters who usually said they did not want to break up slave families – and often did it anyway".[125][126]

American Revolution

[编辑]

From the late 1760s, Washington became increasingly radicalized against the North American colonies' subservient status within the British Empire.[127] In 1774 he was a key participant in the adoption of the Fairfax Resolves which, alongside the assertion of colonial rights, condemned the transatlantic slave trade on moral grounds.[128][119] Washington was a signatory to that entire document, and thus publicly endorsed clause 17 "declaring our earnest wishes to see an entire stop forever put to such wicked, cruel, and unnatural trade."[129]

He began to express the growing rift with Great Britain in terms of slavery, stating in the summer of 1774 that the British authorities were "endeavouring by every piece of Art & despotism to fix the Shackles of Slavry(原文如此)" upon the colonies. Two years later, on taking command of the Continental Army at Cambridge at the start of the American Revolutionary War, he wrote in orders to his troops that "it is a noble Cause we are engaged in, it is the Cause of virtue and mankind...freedom or Slavery must be the result of our conduct."[130] The hypocrisy or paradox inherent in slave owners characterizing a war of independence as a struggle for their own freedom from slavery was not lost on the British writer Samuel Johnson, who asked, "How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?"[131][132] As if answering Johnson, Washington wrote to a friend in August 1774, "The crisis is arrived when we must assert our rights, or submit to every imposition that can be heaped upon us, till custom and use shall make us tame and abject slaves, as the blacks we rule over with such arbitrary sway."[133]

Washington shared the common Southern concern about arming African Americans, enslaved or free, and initially refused to accept either into the ranks of the Continental Army. He reversed his position on free African Americans when the royal governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, issued a proclamation in November 1775 offering freedom to rebel-owned slaves who enlisted in the British forces. Three years later and facing acute manpower shortages, Washington approved a Rhode Island initiative to raise a battalion of African-American soldiers[134][135]

Washington gave a cautious response to a 1779 proposal from his young aide John Laurens for the recruitment of 3,000 South Carolinian enslaved workers who would be rewarded with emancipation. He was concerned that such a move would prompt the British to do the same, leading to an arms race in which the Americans would be at a disadvantage, and that it would promote discontent among those who remained enslaved.[136][137][f] In 1780, he suggested to one of his commanders the integration of African-American recruits "to abolish the name and appearance of a Black Corps."[141]

During the war, some 5,000 African Americans served in a Continental Army that was more integrated than any American force before the Vietnam War, and another 1,000 served on American warships. They represented less than three percent of all American forces mobilized, though in 1778 they provided as much as 13% of the Continental Army.[142][143] By the end of the war African-Americans were serving alongside whites in virtually all units other than those raised in the deep south.[141][144]

The first indication of a shift in Washington's thinking on slavery appears during the war, in correspondence of 1778 and 1779 with Lund Washington, who managed Mount Vernon in Washington's absence.[145] In the exchange of letters, a conflicted Washington expressed a desire "to get quit of Negroes", but made clear his reluctance to sell them at a public venue and his wish that "husband and wife, and Parents and children are not separated from each other".[146] His determination not to separate families became a major complication in his deliberations on the sale, purchase and, in due course, emancipation of his own slaves.[147] His restrictions put Lund in a difficult position with two female slaves he had already all but sold in 1778, and Lund's irritation was evident in his request to Washington for clear instructions.[148] Despite Washington's reluctance to break up families, there is little evidence that moral considerations played any part in his thinking at this stage. He sought to liberate himself from an economically unviable system, not to liberate his slaves. They were still a property from which he expected to profit. During a period of severe wartime depreciation, the question was not whether to sell his enslaved people, but when, where, and how best to sell them. Lund sold nine enslaved including the two females, in January 1779.[149][150][151]

Washington's actions at the war's end reveal little in the way of antislavery inclinations. He was anxious to recover his own slaves, and refused to consider compensation for the upwards of 80,000 formerly enslaved people evacuated by the British, demanding without success that the British respect a clause in the Preliminary Articles of Peace which he regarded as requiring the return of all slaves and other American property even if the British had purported to free some of those slaves.[152][153][154] Before resigning his commission in 1783, Washington took the opportunity to give his opinion on the challenges that threatened the existence of the new nation, in his Circular to the States. That circular letter inveighed against “local prejudices” but explicitly declined to name any of them, “leaving the last to the good sense and serious consideration of those immediately concerned.”[153][155]

Confederation years

[编辑]

Emancipation became a major issue in Virginia after liberalization in 1782 of the law regarding manumission, which is the act of an owner freeing his slaves. Before 1782, a manumission had required obtaining consent from the state legislature, which was arduous and rarely granted.[156] After 1782, inspired by the rhetoric that had driven the revolution, it became popular to free slaves. The free African-American population in Virginia rose from some 3,000 to more than 20,000 between 1780 and 1800; the 1800 United States Census tallied about 350,000 slaves in Virginia, and the proslavery interest re-asserted itself around that time.[157][158][159] The historian Kenneth Morgan writes, "...the revolutionary war was the crucial turning-point in [Washington's] thinking about slavery. After 1783...he began to express inner tensions about the problem of slavery more frequently, though always in private..."[160] Although Philip Morgan identifies several turning points and believes no single one was pivotal,[g] most historians agree the Revolution was central to the evolution of Washington's attitudes on slavery.[164][165] It is likely that revolutionary rhetoric about the rights of men, the close contact with young antislavery officers who served with Washington – such as Laurens, the Marquis de Lafayette and Alexander Hamilton – and the influence of northern colleagues were contributory factors in that process.[166][167][h]

Washington was drawn into the postwar abolitionist discourse through his contacts with antislavery friends, their transatlantic network of leading abolitionists and the literature produced by the antislavery movement,[170] though he was reluctant to volunteer his own opinion on the matter and generally did so only when the subject was first raised with him.[160] At his death, Washington's extensive library included at least seventeen publications on slavery. Six of them had been collated into an expensively bound volume titled Tracts on Slavery, indicating that he attached some importance to that selection. Five of the six were published in or after 1788.[i] All six shared common themes that slaves first had to be educated about the obligations of liberty before they could be emancipated, a belief Washington is reported to have expressed himself in 1798, and that abolition should be realized by a gradual legislative process, an idea that began to appear in Washington's correspondence during the Confederation period.[172][173]

Washington was not impressed by what Dorothy Twohig – a former editor-in-chief of The Washington Papers – described as the "imperious demands" and "evangelical piety" of Quaker efforts to advance abolition, and in 1786 he complained about their "tamper[ing] with & seduc[ing]" slaves who "are happy & content to remain with their present masters".[174][175] Only the most radical of abolitionists called for immediate emancipation. The disruption to the labor market and the care of the elderly and infirm would have created enormous problems. Large numbers of unemployed poor, of whatever color, was a cause for concern in 18th-century America, to the extent that expulsion and foreign resettlement was often part of the discourse on emancipation.[176] A sudden end to slavery would also have caused a significant financial loss to slaveowners whose human property represented a valuable asset. Gradual emancipation was seen as a way of mitigating such a loss and reducing opposition from those with a financial self-interest in maintaining slavery.[177]

In 1783, Lafayette proposed a joint venture to establish an experimental settlement for freed slaves which, with Washington's example, "might render it a general practise", but Washington demurred. As Lafayette forged ahead with his plan, Washington offered encouragement but expressed concern in 1786 about "much inconvenience and mischief" an abrupt emancipation might generate, and he gave no tangible support to the idea.[150][178][j]

Washington expressed support for emancipation legislation to prominent Methodists Thomas Coke and Francis Asbury in 1785, but declined to sign their petition which (as Coke put it) asked "the General Assembly of Virginia, to pass a law for the immediate or gradual emancipation of all the slaves".[181][182][183] Washington privately conveyed his support for such legislation to most of the great men of Virginia,[184][181] and promised to comment publicly on the matter by letter to the Virginia Assembly if the Assembly would begin serious deliberation about the Methodists' petition.[185][183] The historian Lacy Ford writes that Washington may have dissembled: "In all likelihood, Washington was honest about his general desire for gradual emancipation but dissembled about his willingness to speak publicly on its behalf; the Mount Vernon master almost certainly reasoned that the legislature would table the petition immediately and thus release him from any obligation to comment publicly on the matter." The measure was rejected without any dissent in the Virginia House of Delegates, because abolitionist legislators quickly backed down rather than suffer inevitable defeat.[181][184][185] Washington wrote in despair to Lafayette: "Some petitions were presented to the Assembly at its last session for the abolition of slavery, but they could scarce obtain a reading."[183] James Thomas Flexner’s interpretation is somewhat different from Lacy Ford’s: "Washington was willing to back publicly the Methodists' petition for gradual emancipation if the proposal showed the slightest possibility of being given consideration by the Virginia legislature."[183] Flexner adds that, if Washington had been more audacious in pursuing emancipation in Virginia, then "he undoubtedly would have failed to achieve the end of slavery, and he would certainly have made impossible the role he played in the Constitutional Convention and the Presidency."[186]

Henriques identifies Washington's concern for the judgement of posterity as a significant factor in Washington's thinking on slavery, writing, "No man had a greater desire for secular immortality, and [Washington] understood that his place in history would be tarnished by his ownership of slaves."[187] Philip Morgan similarly identifies the importance of Washington's driving ambition for fame and public respect as a man of honor;[167] in December 1785, the Quaker and fellow Virginian Robert Pleasants "[hit] Washington where it hurt most", Morgan writes, when he told Washington that to remain a slaveholder would forever tarnish his reputation.[188][k] In correspondence the next year with Maryland politician John Francis Mercer, Washington expressed "great repugnance" at buying slaves, stated that he would not buy any more "unless some peculiar circumstances should compel me to it" and made clear his desire to see the institution of slavery ended by a gradual legislative process.[193][194] He expressed his support for abolitionist legislation privately, but widely,[195] sharing those views with leading Virginians,[183] and with other leaders including Mercer and founding father Robert Morris of Pennsylvania to whom Washington wrote:[196]

I can only say that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it – but there is only one proper and effectual mode by which it can be accomplished, and that is by Legislative authority: and this, as far as my suffrage will go, shall never be wanting.

Washington still needed labor to work his farms, and there was little alternative to slavery. Hired labor south of Pennsylvania was scarce and expensive, and the Revolution had cut off the supply of indentured servants and convict labor from Great Britain.[197][37] Washington significantly reduced his slave purchases after the war, though it is not clear whether this was a moral or practical decision; he repeatedly stated that his inventory and its potential progeny were adequate for his current and foreseeable needs.[198][199] Nevertheless, he negotiated with John Mercer to accept six slaves in payment of a debt in 1786 and expressed to Henry Lee a desire to purchase a bricklayer the next year.[175][19][l] In 1788, Washington acquired thirty-three slaves from the estate of Bartholomew Dandridge in settlement of a debt and left them with Dandridge's widow on her estate at Pamocra, New Kent County, Virginia.[204][205] Later the same year, he declined a suggestion from the leading French abolitionist Jacques Brissot to form and become president of an abolitionist society in Virginia, stating that although he was in favor of such a society and would support it, the time was not yet right to confront the issue.[206] Historian James Flexner has written that, generally speaking, "Washington limited himself to stating that, if an authentic movement toward emancipation could be started in Virginia, he would spring to its support. No such movement could be started."[207]

Creation of the U.S. Constitution

[编辑]Washington presided over the Constitutional Convention in 1787, during which it became obvious how explosive the slavery issue was, and how willing the antislavery faction was to accept the preservation of this oppressive institution to ensure national unity and the establishment of a strong federal government. The Constitution allowed but did not require the preservation of slavery, and it deliberately avoided use of the word "slave" which could have been interpreted as authorizing the treatment of human beings as property throughout the country.[208] Each state was allowed to keep it, change it, or eliminate it as they wished, though Congress could make various policies that would affect this decision in each state. As of 1776, slavery was legal in all 13 colonies, but by Washington's death in December 1799 there were eight free states and nine slave states, and that split was considered entirely constitutional.[209]

The support of the southern states for the new constitution was secured by granting them concessions that protected slavery, including the Fugitive Slave Clause, plus clauses that promised Congress would not prohibit the transatlantic slave trade for twenty years, and that empowered (but did not require) Congress to authorize suppression of insurrections such as slave rebellions.[210][211] The Constitution also included the Three-Fifths Compromise which cut both ways: for purposes of taxation and representation, three out of every five slaves would be counted, which meant that each slave state would have to pay less taxes but would also have less representation in Congress than if every slave was counted.[212] After the convention, Washington's support was critical for getting the states to ratify the document.[213]

Presidential years

[编辑]Washington's preeminent position ensured that any actions he took with regard to his own slaves would become a statement in a national debate about slavery that threatened to divide the country. Wiencek suggests Washington considered making precisely such a statement on taking up the presidency in 1789. A passage in the notebook of Washington's biographer David Humphreys[m] dated to late 1788 or early 1789 recorded a statement that resembled the emancipation clause in Washington's will a decade later. Wiencek argues the passage was a draft for a public announcement Washington was considering in which he would declare the emancipation of some of his slaves. It marks, Wiencek believes, a moral epiphany in Washington's thinking, the moment he decided not only to emancipate his slaves but also to use the occasion to set the example Lafayette had urged in 1783.[216] Other historians dispute Wiencek's conclusion; Henriques and Joseph Ellis concur with Philip Morgan's opinion that Washington experienced no epiphanies in a "long and hard-headed struggle" in which there was no single turning point. Morgan argues that Humphreys' passage is the "private expression of remorse" from a man unable to extricate himself from the "tangled web" of "mutual dependency" on slavery, and that Washington believed public comment on such a divisive subject was best avoided for the sake of national unity.[217][218][126][n]

As president

[编辑]

Washington took up the presidency at a time when revolutionary sentiment against slavery was giving way to a resurgence of proslavery interests. No state considered making slavery an issue during the ratification of the new constitution, southern states reinforced their slavery legislation and prominent antislavery figures were muted about the issue in public. Washington understood there was little widespread organized support for abolition.[222] He had a keen sense both of the fragility of the fledgling Republic and of his place as a unifying figure, and he was determined not to endanger either by confronting an issue as divisive and entrenched as slavery.[223][224]

He was president of a government that provided materiel and financial support for French efforts to suppress the Saint Domingue slave revolt in 1791, and implemented the proslavery Fugitive Slave Act of 1793.[225][226][227]

On the anti-slavery side of the ledger, in 1789 he signed a reenactment of the Northwest Ordinance which freed any new slaves brought after 1787 into a vast expanse of federal territory, except for slaves escaping from slave states.[228][229] Washington also signed into law the Slave Trade Act of 1794 that banned the involvement of American ships and American exports in the international slave trade.[230] Moreover, according to Washington biographer James Thomas Flexner, Washington as President weakened slavery by favoring Hamilton's economic plans over Jefferson's agrarian economics.[207]

Washington never spoke publicly on the issue of slavery during his eight years as president, nor did he respond to, much less act upon, any of the antislavery petitions he received. He described a 1790 Quaker petition to Congress urging an immediate end to the slave trade as "an illjudged piece of business" that "occasioned a great waste of time", although historian Paul F. Boller has observed that Congress extensively debated that petition only to conclude it had no power to do anything about it, so "The Quaker Memorial may have been a waste of time so far as immediate practical results were concerned."[231]

Late in his presidency, Washington told his Secretary of State, Edmund Randolph, that in the event of a confrontation between North and South, he had "made up his mind to remove and be of the Northern" (i.e. leave Virginia and move up north).[232] In 1798, he imagined just such a conflict when he said, "I can clearly foresee that nothing but the rooting out of slavery can perpetuate the existence of our union."[233][173] But there is no indication Washington ever favored an immediate rather than gradual end to slavery. His abolitionist aspirations for the nation centered around the hope that slavery would disappear naturally over time with the prohibition of slave imports in 1808, the earliest date such legislation could be passed as agreed at the Constitutional Convention.[176][234] Indeed, the dying out of slavery remained possible, until Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin in 1793 which led within five years to a vastly greater demand for slave labor.[235]

As Virginia farmer

[编辑]As well as political caution, economic imperatives remained an important consideration with regard to Washington's personal position as a slaveholder and his efforts to free himself from his dependency on slavery.[236][163] He was one of the largest debtors in Virginia at the end of the war,[237] and by 1787 the business at Mount Vernon had failed to make a profit for more than a decade. Persistently poor crop yields due to pestilence and poor weather, the cost of renovations at his Mount Vernon residence, the expense of entertaining a constant stream of visitors, the failure of Lund to collect rent from Washington's tenant farmers and wartime depreciation all helped to make Washington cash poor.[238][239]

The overheads of maintaining a surplus of slaves, including the care of the young and elderly, made a substantial contribution to his financial difficulties.[241][199] In 1786, the ratio of productive to non-productive slaves was approaching 1:1, and the c. 7,300-英亩(3,000-公顷) Mount Vernon estate was being operated with 122 working slaves. Although the ratio had improved by 1799 to around 2:1, the Mount Vernon estate had grown by only 10 percent to some 8,000英亩(3,200公顷) while the working slave population had grown by 65 percent to 201. It was a trend that threatened to bankrupt Washington.[242][243] The slaves Washington had bought early in the development of his business were beyond their prime and nearly impossible to sell, and from 1782 Virginia law made slaveowners liable for the financial support of slaves they freed who were too young, too old or otherwise incapable of working.[244][245]

During his second term, Washington began planning for a retirement that would provide him "tranquillity with a certain income".[246] In December 1793, he sought the aid of the British agriculturalist Arthur Young in finding farmers to whom he would lease all but one of his farms, on which his slaves would then be employed as laborers.[247][248] The next year, he instructed his secretary Tobias Lear to sell his western lands, ostensibly to consolidate his operations and put his financial affairs in order. Washington concluded his instructions to Lear with a private passage in which he expressed repugnance at owning slaves and declared that the principal reason for selling the land was to raise the finances that would allow him to liberate them.[236][249] It is the first clear indication that Washington's thinking had shifted from selling his slaves to freeing them.[246] In November the same year (1794), Washington declared in a letter to his friend and neighbor Alexander Spotswood: "Were it not then, that I am principled agt.(原文如此) selling Negroes, as you would Cattle in the market, I would not, in twelve months from this date, be possessed of one as a slave."[250][251]

In 1795 and 1796, Washington devised a complicated plan that involved renting out his western lands to tenant farmers to whom he would lease his own slaves, and a similar scheme to lease the dower slaves he controlled to Dr. David Stuart for work on Stuart's Eastern Shore plantation. This plan would have involved breaking up slave families, but it was designed with an end goal of raising enough finances to fund their eventual emancipation (a detail Washington kept secret) and prevent the Custis heirs from permanently splitting up families by sale.[252][253][o]

None of these schemes could be realized because of his failure to sell or rent land at the right prices, the refusal of the Custis heirs to agree to them and his own reluctance to separate families.[255][256] Wiencek speculates that, because Washington gave such serious consideration to freeing his slaves knowing full well the political ramifications that would follow, one of his goals was to make a public statement that would sway opinion towards abolition.[257] Philip Morgan argues that Washington freeing his slaves while President in 1794 or 1796 would have had no profound effect, and would have been greeted with public silence and private derision by white southerners.[258]

Wiencek writes that if Washington had found buyers for his land at what seemed like a fair price, this plan would have ultimately freed "both his own and the slaves controlled by Martha’s family",[259] and to accomplish this goal Washington would "yield up his most valuable remaining asset, his western lands, the wherewithal for his retirement."[260] Ellis concludes that Washington prioritized his own financial security over the freedom of the enslaved population under his control, and writes, on Washington's failure to sell the land at prices he thought fair, "He had spent a lifetime acquiring an impressive estate, and he was extremely reluctant to give it up except on his terms."[261] In discussing another of Washington's plans, drawn up after he had written his will, to transfer enslaved workers to his estates in western Virginia, Philip Morgan writes, "Indisputably, then, even on the eve of his death, Washington was far from giving up on slavery. To the last, he was committed to making profits, even at the expense of the disruptions such transfers would indisputably have wrought on his slaves."[262]

As Washington subordinated his desire for emancipation to his efforts to secure financial independence, he took care to retain his slaves.[263] From 1791, he arranged for those who served in his personal retinue in Philadelphia while he was President to be rotated out of the state before they became eligible for emancipation after six months residence per Pennsylvanian law. Not only would Washington have been deprived of their services if they were freed, most of the slaves he took with him to Philadelphia were dower slaves, which meant that he would have had to compensate the Custis estate for the loss. Because of his concerns for his public image and that the prospect of emancipation would generate discontent among the slaves before they became eligible for emancipation, he instructed that they be shuffled back to Mount Vernon "under pretext that may deceive both them and the Public".[264]

Washington spared no expense in efforts to recover Hercules and Judge when they absconded. In Judge's case, Washington persisted for three years. He tried to persuade her to return when his agent eventually tracked her to New Hampshire, but refused to promise her freedom after his death; "However well disposed I might be to a gradual emancipation", he said, "or even to an entire emancipation of that description of People (if the latter was in itself practicable at this moment) it would neither be politic or just to reward unfaithfulness with a premature preference". Both Hercules and Judge eluded capture.[16] Washington's search for a new chef to replace Hercules in 1797 is the last known instance in which he considered buying a slave, despite his resolve "never to become the Master of another Slave by purchase"; in the end he chose to hire a white chef.[265]

Attitude to race

[编辑]

Historian Joseph Ellis writes that Washington did not favor the continuation of legal slavery, and adds "[n]or did he ever embrace the racial arguments for black inferiority that Jefferson advanced....He saw slavery as the culprit, preventing the development of diligence and responsibility that would emerge gradually and naturally after emancipation."[266] Other historians, such as Stuart Leibinger, agree with Ellis that, "Unlike Jefferson, Washington and Madison rejected innate black inferiority...."[267]

The historian James Thomas Flexner says that the charge of racism has come from historical revisionism and lack of investigation. Flexner has pointed out that slavery was, "Not invented for blacks, the institution was as old as history and had not, when Washington was a child, been officially challenged anywhere."[207]

Kenneth Morgan writes that, "Washington's engrained sense of racial superiority to African Americans did not lead to expressions of negrophobia...Yet Washington wanted his white workers to be housed away from the blacks at Mt. Vernon, believing that close racial intermixture was undesirable."[268] According to historian Albert Tillson, one reason why enslaved black people were lodged separately at Mount Vernon is because Washington felt that some white workers had habits that were "not good" (e.g., Tillson mentions instances of "interracial drinking" in the Chesapeake area), and another reason is that, Tillson reports, Washington "expected such accommodations would eventually disgust the white family."[269]

Philip Morgan writes that "The youthful Washington revealed prejudices toward blacks, quite natural for the day" and that "blackness, in his mind, was synonymous with uncivilized behaviour."[270] Washington's prejudices were not hard and fast; his retention of African-Americans in the Virginia Regiment contrary to the rules, his employment of African-American overseers, his use of African-American doctors and his praise for the "great poetical Talents" of the African-American poet Phillis Wheatley, who had lauded him in a poem in 1775, show that he recognized the skills and talents of African-Americans.[271] Historian Henry Wiencek rendered this judgment:[272]

“If you look at Washington’s will, he’s not conflicted over the place of African Americans at all,” Wiencek said in an interview. “From one end of his papers to the other, I looked for some sense of racism and found none, unlike Jefferson, who’s explicit on his belief in the inferiority of Black people. In his will, Washington authored a bill of rights for Black people and said they should be taught to read and write. They were Americans, with the right to live here, to be educated, and to work productively as free people.”

The views of Martha Washington about slavery and race were different from her husband's, and were less favorable to African Americans. For example, she said in 1795 that, "The Blacks are so bad in their nature that they have not the least grat[i]tude for the kindness that may be shewed to them." She refused to follow the example he set by emancipating his slaves, and instead she bequeathed the only slave she directly owned (named Elish) to her grandson.[273][274]

Posthumous emancipation

[编辑]

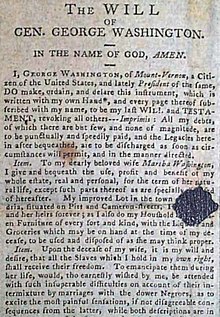

In July 1799, five months before his death, Washington wrote his will, in which he stipulated that his slaves should be freed. In the months that followed, he considered a plan to repossess tenancies in Berkeley and Frederick Counties and transferring half of his Mount Vernon slaves to work them. It would, Washington hoped, "yield more nett profit" which might "benefit myself and not render the [slaves'] condition worse", despite the disruption such relocation would have had on the slave families. The plan died with Washington on December 14, 1799.[275][p]

Washington's slaves were the subjects of the longest provisions in the 29-page will, taking three pages in which his instructions were more forceful than in the rest of the document. His valet, William Lee, was freed immediately and his remaining 123 slaves were to be emancipated on the death of Martha.[277][278] The deferral was intended to postpone the pain of separation that would occur when his slaves were freed but their spouses among the dower slaves remained in bondage, a situation which affected 20 couples and their children. It is possible Washington hoped Martha and her heirs who would inherit the dower slaves would solve this problem by following his example and emancipating them.[279][280][75] Those too old or infirm to work were to be supported by his estate, as mandated by state law.[281] In the late 1790s, about half the enslaved population at Mount Vernon was too old, too young, or too infirm to be productive.[282]

Washington went beyond the legal requirement to support and maintain younger slaves until adulthood, stipulating that those children whose education could not be undertaken by parents were to be taught reading, writing, and a useful trade by their masters and then be freed at the age of 25.[281] He forbade the sale or transportation of any of his slaves out of Virginia before their emancipation.[278] Including the Dandridge slaves, who were to be emancipated under similar terms, more than 160 slaves would be freed.[204][205] Although Washington was not alone among Virginian slaveowners in freeing their slaves, he was unusual among those doing it for doing it so late, after the post-revolutionary support for emancipation in Virginia had faded. He was also unusual for being the only slaveowning Founding Father to do so.[283] Other founders (if not founding fathers) freed their slaves, including John Dickinson and Caesar Rodney who both did so in Delaware.[284]

Aftermath

[编辑]

Any hopes Washington may have had that his example and prestige would influence the thinking of others, including his own family, proved to be unfounded. His action was ignored by southern slaveholders, and slavery continued at Mount Vernon.[285][286] Already from 1795, dower slaves were being transferred to Martha's three granddaughters as the Custis heirs married.[287] Martha felt threatened by being surrounded with slaves whose freedom depended on her death and freed her late husband's slaves on January 1, 1801.[288][q]

Able-bodied slaves were freed and left to support themselves and their families.[290] Within a few months, almost all of Washington's former slaves had left Mount Vernon, leaving 121 adult and working-age children still working the estate. Five freedwomen were listed as remaining: an unmarried mother of two children; two women, one of them with three children, married to Washington slaves too old to work; and two women who were married to dower slaves.[291] William Lee remained at Mount Vernon, where he worked as a shoemaker.[292] After Martha's death on May 22, 1802, most of the remaining dower slaves passed to her grandson, George Washington Parke Custis, to whom she bequeathed the only slave she held in her own name.[293]

There are few records of how the newly freed slaves fared.[294] Custis later wrote that "although many of them, with a view to their liberation, had been instructed in mechanic trades, yet they succeeded very badly as freemen; so true is the axiom, 'that the hour which makes man a slave, takes half his worth away'". The son-in-law of Custis's sister wrote in 1853 that the descendants of those who remained slaves, many of them now in his possession, had been "prosperous, contented and happy", while those who had been freed had led a life of "vice, dissipation and idleness" and had, in their "sickness, age and poverty", become a burden to his in-laws.[295] Such reports were influenced by the innate racism of the well-educated, upper-class authors and ignored the social and legal impediments that prejudiced the chances of prosperity for former slaves, which included laws that made it illegal to teach freedpeople to read and write and, in 1806, required newly freed slaves to leave the state.[296][297]

There is evidence that some of Washington's former slaves were able to buy land, support their families and prosper as free people. By 1812, Free Town in Truro Parish, the earliest known free African-American settlement in Fairfax County, contained seven households of former Washington slaves. By the mid 1800s, a son of Washington's carpenter Davy Jones and two grandsons of his postilion Joe Richardson had each bought land in Virginia. Francis Lee, younger brother of William, was well known and respected enough to have his obituary printed in the Alexandria Gazette on his death at Mount Vernon in 1821. Sambo Anderson – who hunted game, as he had while Washington's slave, and prospered for a while by selling it to the most respectable families in Alexandria – was similarly noted by the Gazette when he died near Mount Vernon in 1845.[298] Research published in 2019 has concluded that Hercules worked as a cook in New York, where he died on May 15, 1812.[299]

A decade after Washington's death, the Pennsylvanian jurist Richard Peters wrote that Washington's servants "were devoted to him; and especially those more immediately about his person. The survivors of them still venerate and adore his memory." In his old age, Anderson said he was "a much happier man when he was a slave than he had ever been since", because he then "had a good kind master to look after all my wants, but now I have no one to care for me".[300] When Judge was interviewed in the 1840s, she expressed considerable bitterness, not at the way she he had been treated as a slave, but at the fact that she had been enslaved. When asked, having experienced the hardships of being a freewoman and having outlived both husband and children, whether she regretted her escape, she replied, "No, I am free, and have, I trust, been made a child of God by [that] means."[301]

Political legacy

[编辑]Washington's will was both private testament and public statement on the institution.[278][220] It was published widely – in newspapers nationwide, as a pamphlet which, in 1800 alone, extended to thirteen separate editions, and included in other works – and became part of the nationalist narrative.[302] In the eulogies of the antislavery faction, the inconvenient fact of Washington's slaveholding was downplayed in favor of his final act of emancipation. Washington "disdained to hold his fellow-creatures in abject domestic servitude," wrote the Massachusetts Federalist Timothy Bigelow before calling on "fellow-citizens in the South" to emulate Washington's example. In this narrative, Washington was a proto-abolitionist who, having added the freedom of his slaves to the freedom from British slavery he had won for the nation, would be mobilized to serve the antislavery cause.[303]

An alternative narrative more in line with proslavery sentiments embraced rather than excised Washington's ownership of slaves. Washington was cast as a paternal figure, the benevolent father not only of his country but also of a family of slaves bound to him by affection rather than coercion.[304] In this narrative, slaves idolized Washington and wept at his deathbed, and in an 1807 biography, Aaron Bancroft wrote, "In domestick(原文如此) and private life, he blended the authority of the master with the care and kindness of the guardian and friend."[305] The competing narratives allowed both North and South to claim Washington as the father of their countries during the American Civil War that ended slavery more than half a century after his death.[306]

There is tension between Washington's stance on slavery, and his broader historical role as a proponent of liberty. He was a slaveholder who led a war for liberty, and then led the establishment of a national government that secured liberty for many of its citizens, and historians have considered this a paradox.[132] The historian Edmund Sears Morgan explained that Washington was not alone in this regard: "Virginia produced the most eloquent spokesmen for freedom and equality in the entire United States: George Washington, James Madison, and, above all, Thomas Jefferson. They were all slaveholders and remained so throughout their lives."[307] Washington recognized this paradox, rejected the notion of black inferiority, and was somewhat more humane than other slaveowners, but failed to publicly become an active supporter of emancipation laws due to Washington's fears of disunion, the racism of many other Virginians, the problem of compensating owners, slaves' lack of education, and the unwillingness of Virginia’s leaders to seriously consider such a step.[267][266]

Memorial

[编辑]In 1929, a plaque was embedded in the ground at Mount Vernon less than 50码(45米) from the crypt housing the remains of Washington and Martha, marking a plot neglected by both groundsmen and tourist guides where slaves had been buried in unmarked graves. The inscription read, "In memory of the many faithful colored servants of the Washington family, buried at Mount Vernon from 1760 to 1860. Their unidentified graves surround this spot." The site remained untended and ignored in the visitor literature until the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association erected a more prominent monument surrounded with plantings and inscribed, "In memory of the Afro Americans who served as slaves at Mount Vernon this monument marking their burial ground dedicated September 21, 1983." In 1985, a ground-penetrating radar survey identified sixty-six possible burials. As of late 2017, an archaeological project begun in 2014 has identified, without disturbing the contents, sixty-three burial plots in addition to seven plots known before the project began.[308][309][310]

Notes

[编辑]- ^ 华盛顿的居所位于宅第农场(Mansion House Farm)中,农场内种有蔬果和药草,以供华盛顿取用,此外农场内还种植了一些花卉和异国植物。农场内还有养马和骡子的马厩,以及种有热带植物的温室。铁匠、木工、制桶、食物的生产和储存、纺线、织布和制鞋等需要技艺的工作,也在宅第农场中其他的建筑中进行,至于主要出售到市场上的农作物,则由宅第农场周遭1.5英里(2.4千米)到3英里(4.8千米)范围内的四座农场负责生产,它们分别叫做“道格溪农场(Dogue Run Farm)”、“泥坑农场(Muddy Hole Farm)”、“联合农场(Union Farm)”(从原先的费里农场和法国农场(French's Farm)合并而来),以及“河流农场(River Farm)”[10]。庄园内有一名农场经理,负责经营事务,直接听命于华盛顿,而华盛顿在其他五个农场内,各雇有一名监工[11]

- ^ 其馀6名奴隶被登记为死亡或是无行为能力[20]。

- ^ There is an oral tradition among the descendants of the freedman West Ford that he was the son of Washington and Venus, an enslaved woman belonging to Washington's brother John Augustine Washington. A case made by the historian Henry Wiencek is, according to the historian Philip Morgan, "so circumstantial as to be fanciful", and there is no evidence that Washington ever met Venus, let alone fathered a child by her.[85][86]

- ^ In an 1833 interview, Washington's nephew Lawrence Lewis related a conversation with one of Washington's carpenters who reported an incident where, having made a mistake, he was given "such a slap on the side of my head that I whirled round like a top". If a valet failed to properly clean Washington's boots ready for the morning, "the servant got them about his head but without the Genl. betraying any excitement beyond the effort of the moment – in a minute afterwards he was no less calm & collected than usual."[114]

- ^ Henriques is Professor of History Emeritus at George Mason University and member of the Mount Vernon committee of George Washington Scholars.[124]

- ^ South Carolinian leaders were outraged when Congress passed resolutions, which Wiencek suggests was the first Emancipation Proclamation, supporting the proposal and threatened to withdraw from the war if it was enacted. Washington had known the scheme would encounter significant resistance in South Carolina, and was not surprised when it eventually failed.[138][139] Wiencek discusses the possibility that Washington's concern about slave discontent following the recruitment of South Carolinian slaves would spread to his own slaves and therefore "resisted a recruitment plan that might lead to the loss of his property, despite compelling military necessity".[140]

- ^ Philip Morgan identifies four turning points: the switch from tobacco to grain crops in the 1760s and the realization of the economic inefficiencies of the institution;[118] the broadening of Washington's horizons during the American Revolution and the principles on which it was fought;[161] the influence of abolitionists such as Lafayette, Coke, Asbury and Pleasants in the mid 1780s and Washington's support for abolition by a gradual legislative process;[162] and Washington's attempts to disentangle himself from slavery in the mid 1790s.[163]

- ^ In their general histories, the historians Joseph Ellis and John E. Ferling include Washington's experience of seeing African-Americans fighting for the cause as another factor.[168][169]

- ^ Tracts on Slavery was one volume in a set of thirty-six that Washington had bound probably sometime after 1795. The volumes covered subjects that generally were of importance to him, such as agriculture, the Revolution, the Society of the Cincinnati and politics. The single pre-1788 pamphlet of the six in Tracts on Slavery was A Serious Address to the Rulers of America, on the Inconsistency of Their Conduct Respecting Slavery, published in 1783. It was the first pamphlet in the volume, and Washington had written his signature on the cover, as he did with the first pamphlet in each of the thirty-six volumes. Of the eleven pamphlets on slavery that were, presumably, not considered to be worth binding, eight were published before 1788. One of them, published in 1785, was never read. The implication is that Washington became more interested in the subject in the early 1790s.[171]

- ^ The two discussed slavery when Lafayette visited Washington at Mount Vernon in August 1784, though Washington thought the time was not yet ripe for a resolution and questioned how a Virginia plantation could be run without slave labor. On returning to France, Lafayette purchased a plantation in the French colony of Cayenne, modern-day French Guiana, and advised Washington of his progress by letter in 1786. Lafayette had taken concerns about the abrupt emancipation of slaves into account, paying and educating the slaves he settled on the plantation before freeing them. He became a leading figure in the French movement against the slave trade and a corresponding member of the British movement. Washington would not have known of Lafayette's antislavery activities in Cayenne or Europe from Lafayette himself; although the two continued to correspond for the rest of Washington's life, the subject of slavery virtually disappeared from their letters. The Cayenne experiment came to an end in 1792, when the plantation was sold by the French Revolutionary government after Lafayette's imprisonment by the Austrians.[179][180]

- ^ John Rhodehamel, former archivist at Mount Vernon and curator of American historical manuscripts at the Huntington Library,[189] characterizes Washington as someone who desired "above all else the kind of fame that meant a lasting reputation as a man of honor."[190] According to Gordon S. Wood, "Many of [Washington's] actions after 1783 can be understood only in terms of this deep concern for his reputation as a virtuous leader."[191] Ron Chernow writes, "...the thought of his high destined niche in history was never far from [Washington's] mind."[192]

- ^ The sources are contradictory on Washington's negotiations to accept slaves from Mercer in settlement of a debt. Kenneth Morgan states that Washington purchased the slaves,[200] as does Twohig, though she reports five slaves.[19] Philip Morgan states that the negotiations with Mercer fell through,[201] as does Hirschfeld.[202] Peter Henriques reports that Washington purchased a bricklayer in 1787, but Kenneth Morgan, Twohig and Hirschfeld report only on negotiations to buy one without confirming that he did.[203]

- ^ Humphreys was a former aide to Washington and had begun an eighteen-month stay at Mount Vernon in 1787 to assist Washington with his correspondence and write his biography.[215]

- ^ Wiencek bases his argument on the fact that the passage was written in the past tense and appears in Humphreys' notebook amid drafts Humphreys had written for public statements Washington was to make about assuming the presidency.[216] Philip Morgan points out that the passage was Humphreys' words in Washington's voice and appears just after a summary Humphreys had written of Thomas Clarkson's 1788 An Essay on the Impolicy of the African Slave Trade.[219] Kenneth Morgan characterizes the passage as "a remark made in [Washington's] voice by David Humphreys".[220] Fritz Hirschfeld writes that the passage was written by Humphreys during direct dictation or from memory of Washington's exact words, and believes it highly improbable that they were not Washington's own words.[221]

- ^ The dower slaves had already begun to be transferred to Martha's granddaughters as the Custis heirs married. Young Martha brought sixty-one slaves to her marriage with Thomas Peter in 1795, Eliza married Thomas Law the next year and Nelly was wed to Lawrence Lewis in 1799. Peter had begun selling off slaves soon after his marriage, splitting up families and systematically separating girls as young as four years old from their parents. Wiencek suggests Martha's servant Oney Judge, who as a dower slave was destined to become Custis property, fled from Philadelphia in 1796 to avoid being sold.[254]

- ^ Philip Morgan speculates that, had the plan proved profitable, Washington might have changed his will and retracted the manumission of his slaves.[276]

- ^ There is a suggestion that slaves were implicated in starting a fire at the main residence after Washington's death, and there were rumors that Martha was in danger, including one that slaves planned to poison her. Other factors that may have influenced her decision to free Washington's slaves early include concerns about the expense of maintaining slaves that were not necessary to operate the estate and about discontent among the dower slaves if they continued to mix with slaves who were to be freed.[289]

References

[编辑]- ^ Wiencek 2003, pp. 41–43

- ^ Wiencek 2003 43–46

- ^ Henriques 2008, p. 146

- ^ Chernow 2010, pp. 22–28

- ^ Chernow 2010, pp. 82, 137

- ^ Chernow 2010, pp. 201, 202

- ^ Ferling 2009, p. 66

- ^ Longmore 1988, p. 105

- ^ Chernow 2010, pp. 113–115, 137

- ^ Thompson 2019, p. 4

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 78–79

- ^ Hirschfeld 1997, p. 11

- ^ Morgan 2000, p. 281

- ^ Hirschfeld 1997, pp. 11–12

- ^ Wiencek 2003, p. 81

- ^ 16.0 16.1 Ellis 2004, p. 260

- ^ 17.0 17.1 Morgan 2005, p. 407 n7

- ^ Haworth 1925, p. 192, cited in Hirschfeld 1997, p. 12

- ^ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Twohig 2001, p. 123

- ^ Hirschfeld 1997, p. 16

- ^ Morgan 2000, pp. 281–282, 298

- ^ Hirschfeld 1997, pp. 16–17

- ^ 23.0 23.1 Morgan 2000, p. 282

- ^ Thompson 2019, p. 45

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 53–54

- ^ Ellis 2004, p. 46

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 47, 51

- ^ Morgan 1987, p. 40

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 42, 286

- ^ Thompson 2019, p. 321

- ^ Vail 1947, pp. 81–82

- ^ Chernow 2010, p. 436.

- ^ Williams, Pat. Extreme Dreams Depend on Teams, p. 73 (Center Street, 2009).

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 30, 78–79, 105–106

- ^ Wiencek 2003, p. 93

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 33–34

- ^ 37.0 37.1 Morgan 2000, p. 283

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 35–36, 319

- ^ Thompson 2019, p. 105

- ^ 40.0 40.1 Morgan 2005, p. 410

- ^ 41.0 41.1 Twohig 2001, p. 117

- ^ Morgan 2000, p. 286

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 117–118

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 109–111

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 86, 343–344

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 106–107, 122–123

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 110, 124, 134

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 123–124

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 120, 125

- ^ Wiencek 2003, p. 100

- ^ 51.0 51.1 Twohig 2001, p. 116

- ^ Ellis 2004, p. 46

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 162–164, 166–167

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 162, 167, 169

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 168–169

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 168, 170

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 170–172

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 175–176

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 177–178

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 179–181

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 244–245

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 221–222, 245

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 229–231

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 193–194

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 197, 231

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 194, 195–196, 232

- ^ Thompson 2019, p. 128

- ^ Wiencek 2003, pp. 122–123

- ^ Thompson 2019, p. 132

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 134, 136, 202

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 127, 130–131, 132

- ^ Wiencek 2003, p. 123

- ^ 73.0 73.1 Thompson 2019, p. 135

- ^ Morgan 2005, p. 421

- ^ 75.0 75.1 Thompson 2019, p. 309

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 151–152

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 158–160

- ^ Thompson 2019, p. 203

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 211–213

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 213–214

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 208–209

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 209, 210–211

- ^ Chernow 2010, p. 362

- ^ Henriques, Peter. "'The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret': George Washington and Slavery", George Mason University (July 25, 2001).

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 147–151

- ^ Morgan 2005, pp. 419, 420 n26

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 136, 138–139

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 140–141

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 141–142

- ^ Thompson 2019, pp. 136, 140

- ^ Thompson, Mary. "'The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret'", MountVernon.org (accessed 30 Jun 2020).