无政府主义社区列表

外观

| 系列条目 |

| 无政府主义 |

|---|

|

无政府主义社区指任何由无政府主义者建立的或按照无政府主义哲学和原则运作的社会及某社会的部分。自19世纪以来,无政府主义者已经创立了大量自治区并参与了各种各样的实践活动。本列表的许多例子表明,一个社区能够参照无政府主义的哲学路线组织起来并促进各地的无政府主义运动、反经济学和反文化的发展。这些例子中有无政府主义者进行社会实验而建立的意识社区或社区计划,比如集体企业及合作社;一些大众社会或受到无政府主义影响,或本身就是明确的无政府主义革命所产生的无政府社会,后者的例子包括乌克兰的马赫诺运动[2]、西班牙的革命加泰罗尼亚[3]和满洲的在满韩族总联合会[4]。

大众社会

[编辑]

现存的大众社会

[编辑]| 旗帜 | 名称 | 创立时间 | 持续时间 | 位置 | 意识形态 | 参考文献 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 萨尔乌达耶劳务捐赠运动 | 1958年 | 66年1个月2周又6天 | 斯里兰卡 | 佛教无政府主义、甘地主义 | [6] | |

| 埃克萨尔希亚 | 1973年11月14日 | 51年1个月1周又4天 | 希腊雅典 | 无政府主义、社会主义 | [7][8][9][10] | |

| 马里纳莱达 | 1979年4月3日 | 45年8个月3周又1天 | 西班牙塞维利亚 | 共产主义、互助论 | [11] | |

| 埃尔阿尔托邻里委员会联合会 | 1979年11月16日 | 45年1个月1周又2天 | 玻利维亚埃尔阿尔托 | 直接民主、原住民主义 | [12] | |

| 瓦哈卡人民原住民委员会“里卡多·弗洛雷斯·马贡” | 1997年 | 27年11个月3周又3天 | 墨西哥瓦哈卡州 | 原住民主义、马贡主义 | [13] | |

| 巴塞罗那占屋运动 | 2000年 | 24年9个月1周又6天 | 西班牙巴塞罗那 | 无政府主义、自治主义 | [14] | |

| 尊严村 | 2000年12月 | 24年3周又3天 | 美国俄勒冈州波特兰 | 无政府主义 | [15][16][17] | |

| 柏巴沙 | 2001年4月20日 | 23年8个月又5天 | 阿尔及利亚 | 柏柏尔主义、卡拜尔主义 | [18] | |

| 扎奇拉镇 | 2006年6月14日 | 18年6个月1周又4天 | 墨西哥瓦哈卡州 | 原住民主义、马贡主义 | [13] | |

| 保卫区 | 2009年8月3日 | 15年4个月3周又1天 | 法国 | 绿色无政府主义 | [19] | |

| 切兰 | 2011年4月15日 | 13年8个月1周又3天 | 墨西哥米却肯州 | 直接民主、原住民主义 | [20] | |

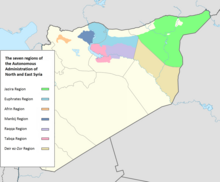

| 罗贾瓦 | 2012年7月19日 | 12年5个月又6天 | 叙利亚 | 民主邦联主义 | [21][22] |

已消亡的大众社会

[编辑]| 旗帜 | 名称 | 创立时间 | 消亡时间 | 持续时间 | 位置 | 意识形态 | 参考文献 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 巴黎公社 | 1871年3月18日 | 1871年5月28日 | 2个月1周又3天 | 法兰西第三共和国巴黎 | 革命社会主义 | [23] | |

| 卡塔赫纳州 | 1873年7月12日 | 1874年1月12日 | 6个月 | 西班牙第一共和国卡塔赫纳 | 州权主义、互助论 | [24] | |

| 斯特兰贾公社 | 1903年8月18日 | 1903年9月8日 | 3周 | 奥斯曼帝国 | 无政府共产主义 | [25] | |

| 下加利福尼亚叛乱 | 1911年1月29日 | 1911年7月22日 | 4个月3周又3天 | 墨西哥下加利福尼亚州 | 马贡主义 | [26] | |

| 莫雷洛斯公社 | 1913年 | 1917年 | 4年2个月又4周 | 墨西哥莫雷洛斯州 | 新萨帕塔主义 | [27][28] | |

| 水兵和建设者苏维埃共和国 | 1917年12月17日 | 1918年2月26日 | 2个月1周又2天 | 爱沙尼亚奈斯岛 | 无政府工团主义 | [29] | |

| 敖德萨苏维埃共和国 | 1918年1月17日 | 1918年3月13日 | 1个月3周又3天 | 乌克兰敖德萨州 | 革命社会主义 | [30] | |

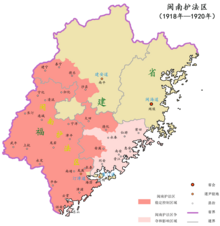

| 闽南护法区 | 1918年9月1日 | 1920年8月12日 | 1年11个月1周又4天 | 中国福建省 | 无政府主义、社会主义 | [31][32] | |

| 马赫诺运动 | 1918年11月27日 | 1921年8月28日 | 2年9个月又1天 | 乌克兰 | 无政府共产主义、纲领主义 | [2] | |

| 不莱梅苏维埃共和国 | 1919年1月10日 | 1919年2月4日 | 3周4天 | 魏玛共和国不莱梅 | 革命社会主义 | [33] | |

| 巴伐利亚苏维埃共和国 | 1919年4月12日 | 1919年5月3日 | 3周 | 魏玛共和国巴伐利亚 | 革命社会主义 | [34][35] | |

| 利默里克苏维埃 | 1919年4月15日 | 1919年4月27日 | 1周5天 | 爱尔兰 | 革命社会主义 | [36] | |

| 巴塔哥尼亚叛乱 | 1920年8月 | 1922年2月 | 1年6个月 | 阿根廷圣克鲁斯省 | 无政府工团主义 | [37][38] | |

| 坦波夫叛乱 | 1920年8月19日 | 1921年6月12日 | 9个月3周又3天 | 俄罗斯苏维埃联邦社会主义共和国坦波夫州 | 农业社会主义 | [39] | |

| 喀琅施塔得起义 | 1921年3月1日 | 1921年3月17日 | 1周3天 | 俄罗斯苏维埃联邦社会主义共和国喀琅施塔得 | 无政府工团主义 | [40] | |

| 广州公社 | 1921年4月2日 | 1927年12月13日 | 6年8个月1周又4天 | 中国广州市 | 无政府主义 | [41] | |

| 在满韩族总联合会 | 1929年8月 | 1931年9月 | 2年1个月2周又1天 | 中国满洲 | 无政府共产主义 | [42] | |

| 革命加泰罗尼亚 | 1936年7月21日 | 1939年2月10日 | 2年6个月2周又6天 | 西班牙加泰罗尼亚 | 无政府工团主义 | [3] | |

| 阿斯图里亚斯和莱昂主权委员会 | 1936年9月6日 | 1937年10月21日 | 1年1个月2周又1天 | 西班牙 | 自由意志社会主义 | [43] | |

| 阿拉贡地区防御委员会 | 1936年10月6日 | 1937年8月11日 | 10个月5天 | 西班牙阿拉贡 | 无政府共产主义 | [3] | |

| 朝鲜人民共和国 | 1945年9月12日 | 1946年2月8日 | 4个月3周又6天 | 朝鲜 | 直接民主 | [44] | |

| 西贡公社 | 1945年9月23日 | 1946年1月13日 | 3个月3周 | 越南共和国西贡 | 反帝国主义 | [45] | |

| 上海人民公社 | 1967年1月5日 | 1967年2月24日 | 1个月2周又5天 | 中国上海市 | 革命社会主义 | [46] | |

| 文德兰自由共和国 | 1980年5月3日 | 1980年6月4日 | 1个月1天 | 西德下萨克森州戈莱本 | 反核 | ||

| 反叛萨帕塔自治市镇 | 1994年1月1日 | 2023年11月5日 | 29年10个月又4天 | 墨西哥恰帕斯州 | 新萨帕塔主义 | [47] | |

| 水平性运动 | 2001年12月13日 | 2003年5月25日 | 1年5个月1周又5天 | 阿根廷 | 自治主义、参与型经济 | [48] | |

| 瓦哈卡市 | 2006年6月14日 | 2006年11月27日 | 5个月1周又6天 | 墨西哥瓦哈卡州 | 直接民主、马贡主义 | [13] | |

| 交响乐路 | 2008年2月 | 2009年10月19日 | 1年8个月 | 南非代尔夫特 | 反权威主义 | [12] | |

| 15-M运动 | 2011年5月15日 | 2015年4月11日 | 3年10个月3周又6天 | 西班牙 | 反紧缩、直接民主 | [49] | |

| 盖齐公园公社 | 2013年5月27日 | 2013年8月20日 | 2个月3周又3天 | 土耳其伊斯坦布尔 | 反权威主义 | [49] | |

| 国会山自治区 | 2020年7月8日 | 2020年8月1日 | 3周2天 | 美国西雅图 | 占领抗议 | [50] |

意识社区

[编辑]现存的意识社区:

已消亡的意识社区:

社区计划

[编辑]现存的社区计划

- 十二分之一俱乐部(1981年–今)

- ABC No Rio(1980年–今)

- ACU(1976年–今)

- 爱丁堡自治中心(1997年–今)

- 闪电战大厦(1982年–今)

- 蓝袜书屋(1999年–今)

- 砖屋(1999年–今)

- 卡马斯书屋及信息商店(2007年–今)

- 坎马斯德乌(2001年–今)

- 坎别斯(1997年–今)

- 卡斯奇纳托奇拉(1992年–今)

- 国际无政府主义研究中心(1957年–今)

- 切咖啡厅(1980年–今)

- 公民媒体中心(1992年–今)

- 浓咖啡(2008年–今)

- 共同大地组织(2005年–今)

- 考利俱乐部(2003年–今)

- 自我管理的社会中心福特普雷内斯蒂诺占屋(1986年5月1日–今)

- C占屋(1989年–今)

- 拨号屋(1970年–今)[65]

- 伦敦DIY空间(2015年–今)

- 埃斯卡莱拉卡拉科拉(1996年–今)

- 外池(1991年–今)

- 火风暴咖啡厅及书屋(2008年5月–今)

- 森林咖啡厅(2000年–今)

- 自由出版社(1886年–今)

- 自由商店(1995年5月1日–今)

- 大裤衩(1984年–今)

- 豪斯曼尼亚(2000年–今)

- 鹿屋(2006年–今)

- 朱拉书屋(1977年–今)

- 农业利益(2002年4月6日–今)

- 伦敦行动资源中心(1999年–今)

- 露西·帕森斯中心(1992年–今)

- 44咖啡厅(1976年–今)

- 马特库瓦艺术村(1993年9月–今)[66]

- 噪音桥(2007年–今)

- OCCII(1982年–今)

- OT301(1999年–今)

- 门房(1980年10月3日–今)

- 红色埃玛书屋咖啡厅(2004年11月–今)

- 红花(1989年–今)

- 罗兹布拉特(1994年–今)

- 加利福尼亚斯拉布城(约1961年-今)

- 斯巴达克斯书屋(1973年–今)

- 苏美克中心(1984年–今)

- 旧市场自治区(1995年–今)

- 青年自由活动(1981年–今)

- 战区集体(1984年–今)

已终止的社区计划

- 121中心(1981–1999年)

- 491画廊(2001–2013年)

- ADM(1997–2019年)

- 阿姆斯特丹颠覆性信息交流中心(1999–2006年)

- 思想银行(2011年11月–2012年1月)

- 宾兹(2006–2013年)

- 比特(1968–1979年)

- 布鲁姆斯伯里社会中心(2011年11月23日–12月22日)

- 棚车书屋(2001–2017年)

- 布莱恩·麦肯齐信息商店(1999–2008年)

- 国会山自治区(2020年)

- 催化剂信息商店(2004–2010年)

- 73中心(2010年9月–12月)

- 伊比利亚中心(1982年4月–8月)

- 奶油城集体(2006年10月–2012年10月31日)

- 蓝色攻击(1980–2003年)

- 罗格工厂(2006-2021年1月)

- 国际主义者书屋(1981–2016年9月)

- 铁轨书社(2003–2012年)

- 诊所(2014–2019年)

- 库库察(1996–2011年)

- 塔赫勒斯艺术馆(1990–2011年)

- 仙境天井(2007–2015年)

- 堡垒艺术(2004年5月–2009年10月15日)

- 真的免费学校(2011年)

- 红与黑咖啡馆(2000–2015年)

- RHINO(1988–2007年)

- 幸运客厅

- 游戏室(2004–2015年)

- 盈余钉子计划(1999–2009年)

- 米拉达占屋(1997–2009年)

- 圣阿格尼斯广场(1969年6月1日–2005年11月30日)

- 青年宫(1982–2007年)

- 阿玛利亚别墅(1990–2012年)

- 自由之地科彭欣克斯泰赫(1968–2010年)

- 沃平自治中心(1981–1982年)

参见

[编辑]参考文献

[编辑]- ^ 1.0 1.1 Osborne, Domenique. Radically wholesome. Metro Times. 2002-11-09 [2011-04-13]. (原始内容存档于2011-03-30).

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Skirda, Alexandre. Nestor Makhno: Anarchy's Cossack. AK Press. 2004. ISBN 1-902593-68-5.

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Dolgoff, Sam. The Anarchist Collectives: Workers' Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939. 1974.

- ^ Cartography of Revolutionary Anarchism. Anarchy In Action. [2017-03-02]. (原始内容存档于2017-03-02).

- ^ Mallett-Outtrim, Ryan. Two decades on: A glimpse inside the Zapatista's capital, Oventic. 2016-08-13 [2019-07-23]. (原始内容存档于2019-07-23).

- ^ Clark, John. The Impossible Community: Realising Communitarian Anarchism. 2013.

- ^ King, Alex; Manoussaki-Adamopoulou, Ioanna. Inside Exarcheia: the self-governing community Athens police want rid of. The Guardian. 2019-08-26 [2020-11-10]. (原始内容存档于2019-12-21).

- ^ Appelbaum, Robert. Anarchy in Exarchia. The Baffler. 2015-02-04 [2020-11-10]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-12).

- ^ 加洛韦, 林赛. 热爱陌生人的欧洲城市. BBC中文. [2021-08-09]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-12) (中文(简体)).

- ^ Rigoutsou, Maria. 希腊抗议活动仍在持续. 德国之声. 2008-12-13 [2021-11-24]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-24) (中文(中国大陆)).

- ^ Hancox, Dan. Marinaleda: Spain's communist model village. The Guardian. 2013-10-20 [2021-08-12]. (原始内容存档于2018-09-06).

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Gelderloos, Peter. How will cities work?. Anarchy Works. San Francisco: Ardent Press. 2010 [2021-08-12]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-07).

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Denham, Diana. Teaching Rebellion: Stories from the Grassroots Mobilization of Oaxaca. Oakland: PM Press. 2008.

- ^ Gelderloos, Peter. To Get To The Other Side: a journey through europe and its anarchist movements. 2009 [2021-08-12]. (原始内容存档于2021-01-19).

- ^ Herring, Chris. Tent City, America. Places. December 2015 [2020-11-10]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-06).

- ^ Speer, Jessie. Right to the Tent City: The Struggle Over Urban Space in Fresno, California (学位论文). Syracuse University. December 2014 [2020-11-10]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-12).

- ^ Hester, Lucas. Sustaining Autonomous Communities in the Modern United States (The United Communities of America) (学位论文). Linfield University. 2017-11-12 [2020-11-10]. (原始内容存档于2020-10-27).

- ^ Collective, CrimethInc. Ex-Workers. Other Rojavas: Echoes of the Free Commune of Barbacha. CrimethInc. [2018-05-16]. (原始内容存档于2018-05-17) (英语).

- ^ G, S; K, G. ZAD: The State of Play. The Brooklyn Rail. 由Janet Koenig翻译. 2018-07-11 [2019-05-04]. (原始内容存档于2019-04-23).

- ^ Pressly, Linda. Cheran: The town that threw out police, politicians and gangsters. BBC. 2016-10-13 [2021-08-12]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-17).

- ^ The Hamilton Institute. The Most Important Thing: Reflections on Solidarity and the Syrian Revolution. 2016-05-13 [2019-07-16]. (原始内容存档于2019-07-16).

- ^ Reid, Nicky. Lessons from Rojava. CounterPunch. 2019-01-14 [2019-12-28]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-12).

- ^ The Paris Commune and the Idea of the State. [2018-09-25]. (原始内容存档于2018-07-16).

- ^ George Woodcock. Anarchism: a history of libertarian movements. Pg. 357

- ^ Khadzhiev, Georgi. The Transfiguration Uprising and the 'Strandzha Commune': The First Libertarian Commune in Bulgaria. Nat︠s︡ionalnoto osvobozhdenie i bezvlastnii︠a︡t federalizŭm [National Liberation and Libertarian Federalism]. 由Firth, Will翻译. Sofia: Artizdat-5. 1992: 99–148 [2021-08-12]. OCLC 27030696. (原始内容存档于2012-09-18) (保加利亚语).

- ^ Uprising in Baja California (PDF). Anarchist Federation. [2013-06-07]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-08-04).

- ^ The Morelos Commune. Global Learning. 2014-02-03 [2021-08-12]. (原始内容存档于2019-07-16).

- ^ Kantowicz, Edward. The Rage of Nations. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. 1999: 241, 242, 243.

- ^ Naissar: the Estonian "Island of Women", Once an Independent Socialist Republic. [2019-07-16]. (原始内容存档于2019-07-16).

- ^ Smele, Jonathan D. Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 1916-1926. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. 2015-11-19: 1155–1156 [2021-08-12]. ISBN 978-1-4422-5281-3. (原始内容存档于2021-08-12).

- ^ 国家历史杂志. 无政府主义 陈炯明与“安那琪”世界. 凤凰网. 2009-04-29 [2020-02-13]. (原始内容存档于2020-02-13) (中文(简体)).

- ^ 周丽卿. 政治、權力與批判:民初劉師復派無政府團體的抵抗與追求. 国史馆馆刊. 2014-12-01, (42): 18 [2021-08-12]. ISSN 1016-2933. (原始内容存档于2021-08-12).

- ^ The Bremerhaven Republic from a syndicalist perspective. (PDF). [2019-07-16]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2016-03-04).

- ^ Hobsbawm, Eric. Revolutionaries: Contemporary Essays. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. 1973. ISBN 0-297-76549-3.

- ^ Horrox, James. Gustav Landauer (1870-1919). [2019-07-16]. (原始内容存档于2019-03-16).

- ^ Forgotten Revolution: Limerick Soviet, 1919. [2019-07-16]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-26).

- ^ Oved, Yaacov. The Uniqueness of Anarchism in Argentina. Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe (Tel Aviv: University of Tel Aviv). 1997, 8 (1) [2021-08-12]. ISSN 0792-7061. OCLC 25122634. (原始内容存档于2013-02-08).

- ^ Colombo, Eduardo, Anarchism in Argentina and Uruguay, Apter, David E.; Joll, James (编), Anarchism Today, Garden City, New York: Anchor Books: 219–220, 1971

- ^ von Geldern, James. The Antonov Rebellion. [2021-08-12]. (原始内容存档于2021-05-17).

- ^ Leonard F. Guttridge. Mutiny: A History of Naval Insurrection. Naval Institute Press. 2006-08-01: 174 [2018-09-25]. ISBN 978-1-59114-348-2. (原始内容存档于2019-05-13).

- ^ Dongyoun Hwang, "Korean Anarchism Before 1945: A Regional and Transnational Approach" in Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Colonial and Postcolonial World, 118.

- ^ Cartography of Revolutionary Anarchism. Anarchy in Action. [2017-03-02]. (原始内容存档于2017-03-02).

- ^ Alexander, Robert. The Anarchists in the Spanish Civil War, Volume 2. Janus Publishing Company Lim. 1999: 844 [2013-04-14]. ISBN 9781857564129. (原始内容存档于2021-08-12).

- ^ Nippon, CIRA. The Post-War Korean Anarchist Movement. Libero International. 1975 [2020-01-22]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-12).

- ^ 1945: The Saigon commune. [2019-07-16]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-26).

- ^ Meisner, Maurice. Mao's China and After: A History of the People's Republic since 1949. Free Press. 1986.

- ^ Flood, Andrew. The Zapatistas, anarchism and 'Direct democracy (27). Anarcho-Syndicalist Review. 1999.

- ^ Natasha Gordon and Paul Chatterton, Taking Back Control: A Journey through Argentina's Popular Uprising, Leeds (UK): University of Leeds, 2004,

- ^ 49.0 49.1 Gelderloos, Peter. The Failure of Nonviolence. 2015.

- ^ Silva, Daniella; Moschella, Matteo. Seattle protesters set up 'autonomous zone' after police evacuate precinct. NBC News. 2020-06-11 [2020-06-12]. (原始内容存档于2020-06-12).

- ^ Hardy, Dennis. Utopian England: Community Experiments, 1900-1945. Psychology Press. 2000: 181 [2021-08-12]. ISBN 978-0-419-24670-1. (原始内容存档于2021-08-12).

- ^ Autry, Curt. Louisa Commune Flourishes for 43 Years. WWBT NBC 12. 2010 [2011-01-12]. (原始内容存档于2011-11-18).

- ^ Bamyeh, Mohammed A. Anarchy as order. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. May 2009: 21. ISBN 978-0-7425-5673-7.

- ^ Frater, Jamie. Listverse.com's Ultimate Book of Bizarre Lists. Berkeley, CA: Ulysses press. 2010-11-01: 516, 517. ISBN 978-1-56975-817-5.

- ^ Coopératives Longo Maï. [2016-08-21]. (原始内容存档于2014-08-02).

- ^ Awra Amba: the anarcho-feminist utopia that actually works. [2018-10-11]. (原始内容存档于2018-10-11).

- ^ Searching For Happiness In 'Utopia'. [2016-03-11]. (原始内容存档于2016-03-03).

- ^ Bailie, William. Josiah Warren, the first American anarchist: a sociological study. Small, Maynard & company. 1906 [2011-07-27]. (原始内容存档于2007-05-30).

- ^ An Experiment in Anarchy: Modern Times, the notorious and short-lived utopian village that preceded Brentwood. [2014-08-09]. (原始内容存档于2014-08-09).

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter. Small Communal Experiments and Why They Fail. 1893 [2021-08-12]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-12).

- ^ 61.0 61.1 Pierce LeWarne, Charles. Utopias on Puget Sound: 1885–1915. Seattle: University of Washington Press. 1975: 168–226. ISBN 0295974443.

- ^ Franks, Benjamin. Rebel Alliances: The Means and Ends of Contemporary British Anarchisms. AK Press/Dark Star. 2006: 4. ISBN 978-1-904859-40-6.

- ^ Headley, Gwyn; Meulenkamp, Wim. Follies, grottoes & garden buildings. Aurum. 1999: 250 [2021-08-12]. ISBN 9781854106254. (原始内容存档于2021-09-04).

- ^ Sanborn, Josh, Review of Edgerton, William, ed., Memoirs of Peasant Tolstoyans in Soviet Russia, H-Russia, H-Review, March 1996 [2018-10-07], (原始内容存档于2018-06-21) (英语)

- ^ See "crass retirement cottage," nest magazine #21, summer 2003, pp 106-121

- ^ Niranjan, Ajit. How an abandoned barracks in Ljubljana became Europe's most successful urban squat. The Guardian. 2015-07-24 [2018-10-07]. ISSN 0261-3077. (原始内容存档于2018-10-07) (英国英语).

扩展阅读

[编辑]- Amster, Randall. Chasing Rainbows: Utopian Pragmatics and the Search for Anarchist Communities. Anarchist Studies. 2001, 9 (1): 29–52 [2021-08-12]. (原始内容存档于2004-12-11).

- Amster, Randall. Restoring (Dis)Order: Sanctions, Resolutions, and "Social Control" in Anarchist Communities. Contemporary Justice Review. 2003, 6 (1): 9–24. S2CID 145108567. doi:10.1080/1028258032000055612.