User:Dkzzl/君士坦丁堡之围 (626年)

| 赛弗·道莱 سيف الدولة | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Gold dinar minted at Baghdad in the names of Nasir al-Dawla and Sayf al-Dawla, 943/4 CE | |||||

| Emir of Aleppo | |||||

| 統治 | 945–967 | ||||

| 前任 | Uthman ibn Sa'id al-Kilabi | ||||

| 繼任 | Sa'd al-Dawla | ||||

| 出生 | 22 June 916 | ||||

| 逝世 | 967年2月9日(50歲) Aleppo, Syria | ||||

| 安葬 | Mayyafariqin (modern Silvan, Turkey) | ||||

| 子嗣 | Sa'd al-Dawla | ||||

| |||||

| Tribe | Banu Taghlib | ||||

| 朝代 | Hamdanid | ||||

| 父親 | Abdallah ibn Hamdan | ||||

| 宗教信仰 | Twelver Shia Islam | ||||

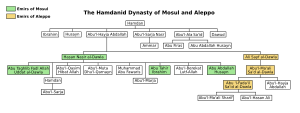

阿里·本·阿布·海贾·阿卜杜拉·本·赫姆丹·本·哈里斯·塔格里比[note 1](阿拉伯语:علي بن أبو الهيجاء عبد الله بن حمدان بن الحارث التغلبي,转写:ʿAlī ibn ʾAbū l-Hayjāʾ ʿAbdallāh ibn Ḥamdān ibn al-Ḥārith al-Taghlibī),916年1月22日– 967年2月9日),通称“赛弗·道莱(سيف الدولة)”,这是他的荣誉称号,意为“王朝的宝剑”。他是赫姆丹王朝的第一位阿勒颇埃米尔,也被认为是这个王朝中最杰出的人物[2],统治北叙利亚大部、西贾兹拉一部;他的长兄哈桑·本·阿卜杜拉·本·赫姆丹(通称纳西尔·道莱)则是摩苏尔的埃米尔。

赛弗·道莱一开始追随兄长纳西尔·道莱,于10世纪40年代尝试掌控虚弱的阿拔斯哈里发政权。失败后,颇具野心的赛弗·道莱转向叙利亚,与同样对叙利亚有野心的埃及的伊赫什德王朝展开竞争。经过两次恶战,他建立了对北叙利亚的统治,以阿勒颇为都,并以麦亚法里根(今锡尔万)为中心统治西贾兹拉,其权力得到伊赫什德王朝和哈里发的承认。直到955年,一系列部落叛乱困扰着他的统治,但都被他击败,成功维持了多数重要阿拉伯部落的忠诚。他热心奖励文化,使阿勒颇的宫廷成为一大文化生活中心,他供养了一批文人,其中包括伟大诗人穆太奈比,使他在阿拉伯历史上享有盛名。

赛弗·道莱也因在阿拉伯-拜占庭战争中发挥的作用而享有盛名。10世纪初拜占庭帝国开始复兴,征服部分穆斯林领地,赛弗·道莱不畏强敌,数次远征深入拜占庭领地,取得数次胜利,在955年前一直占上风。但此后杰出的拜占庭将领尼基弗鲁斯·福卡斯(后来的皇帝)与其副手取得优势,夺取奇里乞亚,甚至于962年短暂占领阿勒颇。赛弗·道莱在生命的最后几年连遭军事失败,自己也因疾病而偏瘫,威望下降,手下数位将领接连叛乱。他于967年初去世,留下一个衰弱的国家,到969年,拜占庭军又夺取安条克与叙利亚沿海,他的后人只能向其称臣纳贡。

生平

[编辑]出身、家族

[编辑]

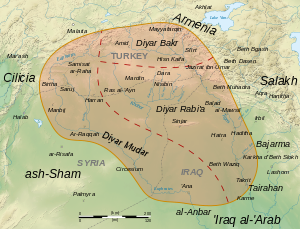

赛弗·道莱生于916年6月22日(部分史料认定是914年)[3][4],本名阿里·本·阿卜杜拉,是阿布· 赫伊贾·阿卜杜拉·本·赫姆丹(死于929年)的次子,赫姆丹王朝的名祖赫姆丹·本·赫姆敦·本·哈里斯之孙[3][5]。赫姆丹一族是台格里卜部落的一支,这一部落自前伊斯兰时代开始就已在贾兹拉(上美索不达米亚)居住[6]。历史上,台格里卜部落一直控制着摩苏尔及其周边地区,但9世纪末,阿拔斯哈里发政府开始加强对这一省份的控制。这引起了部落成员的反抗,赫姆丹·本·赫姆敦就是最坚定的反抗领袖之一。为了抵御阿拔斯王朝,他与摩苏尔以北山中的库尔德人建立了联盟,他的后人常与库尔德人通婚,这一山区民族成为他们军队的重要组成部分,这一点在王朝后来的发展中起了重要作用[5][7][8]。

895年,赫姆丹与他的亲属们战败被俘,但他的儿子侯赛因·本·赫姆丹设法保住了家族的势力。他组织了一支台格里卜族人组成的军队为哈里发服务,以此换取税收的减免,并在阿拔斯政府与当地阿拉伯、库尔德民众间居中调停,在贾兹拉地区建立了威望。赫姆丹家族在10世纪初与巴格达中央政府的关系时常紧张,正是强大的地方根基使得他们幸存下来[5][9]。侯赛因是个常胜将军,在与哈瓦利吉派及突伦王朝的战争中表现出色。但908年他参与了失败的拥立阿卜杜拉·本·穆阿台兹的政变,之后相对失势。919年,他的弟弟易卜拉欣被任命为迪亚尔赖比厄(意为“赖比厄部落之地”,以努赛宾为中心的省份总督,次年他去世后由另一个兄弟达伍德接任[5][10]。赛弗·道莱的父亲阿卜杜拉则在905/06年-913/14年间[註 1]担任摩苏尔的总督(埃米尔),此后在政坛数起数落,925/26年又重新控制摩苏尔。他与权臣穆阿尼斯·穆泽法尔关系密切,并在后者组织的废黜哈里发穆克台迪尔一世拥立嘎希尔的政变中发挥重要作用,但不久后对方反扑,阿卜杜拉被杀[11][12]。

尽管在政变中身亡,但阿卜杜拉已巩固了自己对摩苏尔的控制,成为赫姆丹王朝政权事实上的创建者。他在生命中的最后几年呆在巴格达,于是将摩苏尔交给长子哈桑,未来的纳西尔·道莱统治。阿卜杜拉死后,哈桑的几位叔父试图争夺摩苏尔的统治权,直到935年,他才确保巴格达政府承认他对摩苏尔乃至整个贾兹拉,直到拜占庭帝国边界的广大地区的统治[13][14]。

追随纳西尔·道莱

[编辑]

年轻的阿里(赛弗·道莱)一开始为他的兄长效力。936年,哈桑邀请弟弟投入账下,许诺让他担任迪亚尔贝克尔(阿米达及周边地区)的总督,以换取阿里帮他镇压反叛的麦亚法里根(Mayyafariqin,今锡尔万)总督阿里·本·贾法尔(Ali ibn Ja'far)。阿里成功阻止了亚美尼亚人对贾法尔的援助,并迫使叙吕奇附近居住的盖斯部落成员臣服,确保了对迪亚尔穆达尔北部的控制[8]。以此为基地,他还发动远征援助与拜占庭接壤地区(所谓"关隘地带")的埃米尔们抵御拜占庭军的进攻,并进入亚美尼亚,试图逆转拜占庭对这一地区越来越强的影响[15]。

与此同时,哈桑卷入了与阿拔斯王朝宫廷的冲突。932年哈里发穆克台迪尔被杀之后,阿拔斯中央政府几乎完全崩溃,936年,强大的瓦西特总督穆罕默德·本·拉伊格获得了“埃米尔之埃米尔”的头衔,事实上控制了阿拔斯政府,哈里发拉迪沦为傀儡,庞大的旧文官官僚体系的规模与权力都大大缩减[16]。但拉伊格的地位并不稳固,不久后各方就开始争夺“埃米尔之埃米尔”的权位,以及随之而来的哈里发国的控制权;一场错综复杂的斗争在许多地方势力与突厥军阀间爆发,一直持续到白益王朝于946年取得胜利才告终[17]。

哈桑一开始支持拉伊格,但942年他派人将其刺杀,并为自己取得了“埃米尔之埃米尔”之位,并获赠尊称纳西尔·道莱(阿拉伯语:ناصر الدولة,意为“王朝的捍卫者”)。巴士拉的贝里迪家族(Baridis)也希望控制哈里发政权,继续与哈桑作战,哈桑则派阿里前去镇压。阿里在麦达因面对阿布·侯赛因·贝里迪(Abu'l-Husayn al-Baridi)的军队并取得胜利,因此被任命为瓦西特总督,并获尊称赛弗·道莱(سيف الدولة,意为“王朝的宝剑”),这个尊称比他的本名更有名[8][18]。授予赫姆丹家族两兄弟的尊称也是阿拔斯王朝第一次将著名的含有“王朝(الدولة,al-Dawla)元素的系列尊称赐给维齐尔(首相)以外的人[8]。

然而赫姆丹王朝的成功十分短暂,他们在政治上十分孤立,哈里发国内最强大的两个自治政权——河中地区的萨曼王朝和埃及的伊赫什德王朝并不支持他们。943年,赫姆丹王朝的军队(主要由突厥人、德莱木人、盖尔麦泰派及少量阿拉伯人组成)因报酬问题在突厥人突尊的领导下发动叛乱,迫使两兄弟退出巴格达[8][13][18]。哈里发穆台基任命突尊为“埃米尔之埃米尔”,但不久后与他发生争吵,又向北逃亡,寻求赫姆丹王朝的庇护。突尊又在战场上击败了两兄弟并于944年与他们达成协议,允许他们保有贾兹拉,甚至名义上授予他们对北叙利亚的统治权(这些地区当时尚未被赫姆丹王朝控制),以此换取大量贡品。此后,哈桑(纳西尔·道莱)成为巴格达的附庸,但他继续与白益王朝争夺巴格达的控制权,958/59年,他甚至被迫逃到弟弟的宫廷中寻求庇护,之后阿里(赛弗·道莱)与白益王朝埃米尔穆仪兹·道莱谈判,后者允许哈桑返回摩苏尔[13][19]。

建立阿勒颇埃米尔国

[编辑]

935/36年后,北叙利亚由埃及的伊赫什德王朝统治,939/40年,拉伊格又出兵占领之。942年,纳西尔·道莱刺杀拉伊格并取代了他的位置,试图接管这一地区,特别是拉伊格自己曾任总督的迪亚尔穆达尔省。赫姆丹王朝的军队占领了拜利赫河河谷,但当地的豪强仍然倾向于伊赫什德王朝,赫姆丹王朝的统治十分脆弱。伊赫什德王朝没有直接出兵,选择了支援拉赫拜总督阿德勒·贝克杰米('Adl al-Bakjami),后者攻占了努赛宾,夺取了赛弗·道莱留在那里的财宝,但之后被赛弗·道莱的堂弟侯赛因·本·赛义德击败俘虏,943年5月在巴格达被处决。侯赛因随后进军试图占领自迪亚尔穆达尔至关隘地带(Thughur)的整个拉伊格领地,他以一次突袭拿下了拉卡,944年2月,阿勒颇不战而降[8][20]。此时哈里发穆台基遣使伊赫什德,请求对方帮助他对付那些想要控制他的军阀们。随后哈里发又随赫姆丹王朝到拉卡,但伊赫什德收信后于944年夏天亲自率军到达叙利亚,侯赛因放弃阿勒颇逃跑。流亡的哈里发与伊赫什德在拉卡会面,哈里发确认了伊赫什德对叙利亚的统治,但拒绝随他迁居埃及,埃及君主也拒绝进一步帮助哈里发对付敌人。之后伊赫什德返回埃及,穆台基则深感无力与沮丧而返回巴格达,很快突尊下令把他弄瞎并废黜[8][20][21]。

正是在这种背景下,赛弗·道莱的目光瞄准了叙利亚。之前几年他已多次蒙羞,他在战场上被突尊打败,即使成功刺杀了敌手穆罕默德·本·伊奈勒·突尔朱曼(Muhammad ibn Inal al-Turjuman),他也没能说服穆台基任命他为“埃米尔之埃米尔”。正如现代学者蒂埃里·比昂基所写,兄长在伊拉克的事业失败后,赛弗·道莱“满腹怨气地返回努赛宾,发现自己无事可做、收入不多”,因此把目光转向了叙利亚[8]。纳西尔·道莱似乎也在侯赛因失败后鼓励他的弟弟进军叙利亚,写信给赛弗·道莱,说“叙利亚就在你面前,这片土地上没有人能阻止你获得它”[22]。伊赫什德离开后,赛弗·道莱趁虚带着兄长提供的金钱与军队入侵北叙利亚[20]。他得到了当地基拉卜部落的支持,甚至伊赫什德任命的阿勒颇长官阿布·费斯·奥斯曼·本·赛义德·基拉比(Abu'l-Fath Uthman ibn Sa'id al-Kilabi,属基拉卜部落)也向他投降,陪同他于944年10月29日和平地进入阿勒颇城[22][23][24]。

Conflict with al-Ikhshid

[编辑]Al-Ikhshid reacted, and sent an army north under Abu al-Misk Kafur to confront Sayf al-Dawla, who was then besieging Homs. In the ensuing battle, the Hamdanid scored a crushing victory. Homs then opened its gates, and Sayf al-Dawla set his sights on Damascus. Sayf al-Dawla briefly occupied the city in early 945, but was forced to abandon it in the face of the citizens' hostility.[22] In April 945 al-Ikhshid himself led an army into Syria, although at the same time he also offered terms to Sayf al-Dawla, proposing to accept Hamdanid control over northern Syria and the Thughur. Sayf al-Dawla rejected al-Ikhshid's proposals, but was defeated in battle in May/June and forced to retreat to Raqqa. The Egyptian army proceeded to raid the environs of Aleppo. Nevertheless, in October the two sides came to an agreement, broadly on the lines of al-Ikhshid's earlier proposal: the Egyptian ruler acknowledged Hamdanid control over northern Syria, and even consented to sending an annual tribute in exchange for Sayf al-Dawla's renunciation of all claims on Damascus. The pact was sealed by Sayf al-Dawla's marriage to a niece of al-Ikhshid, and Sayf al-Dawla's new domain received the—purely formal—sanction by the caliph, who also re-affirmed his laqab soon thereafter.[22][25][26]

The truce with al-Ikhshid lasted until the latter's death in July 946 at Damascus. Sayf al-Dawla immediately marched south, took Damascus, and then proceeded to Palestine. There he was confronted once again by Kafur, who defeated the Hamdanid prince in a battle fought in December near Ramla.[22][24] Sayf al-Dawla then retreated to Damascus, and from there to Homs. There he gathered his forces, including large Arab tribal contingents of the Uqayl, Kalb, Uqayl, Numayr, and Kilab, and in spring of 947, he attempted to recover Damascus. He was again defeated in battle, however, and in its aftermath the Ikhshidids even occupied Aleppo in July. Kafur, the de facto Ikhshidid leader after al-Ikhshid's death, did not press his advantage, but instead began negotiations.[22][27]

For the Ikhshidids, the maintenance of Aleppo was less important than southern Syria with Damascus, which was Egypt's eastern bulwark. As long as their control over this region was not threatened, the Egyptians were more than willing to allow the existence of a Hamdanid state in the north. Furthermore, the Ikhshidids realized that they would have difficulty in asserting and maintaining control over northern Syria and Cilicia, which were traditionally oriented more towards the Jazira and Iraq. Not only would Egypt, threatened by this time by the Fatimid Caliphate in the west, be spared the cost of maintaining a large army in these distant lands, but the Hamdanid emirate would also fulfill the useful role of a buffer state against incursions both from Iraq and from Byzantium.[22][25][28] The agreement of 945 was reiterated, with the difference that the Ikhshidids ceased paying tribute for Damascus. The frontier thus established, between Jaziran-influenced northern Syria and the Egyptian-controlled southern part of the country, was to last until the Mamluks seized the entire country in 1260.[25][29]

Sayf al-Dawla, who returned to Aleppo in autumn, was now master of an extensive realm: the north Syrian provinces (Jund Hims, Jund Qinnasrin and the Jund al-'Awasim) in a line running south of Homs to the coast near Tartus, and most of Diyar Bakr and Diyar Mudar in the western Jazira. He also exercised a—mostly nominal—suzerainty over the towns of the Byzantine frontier in Cilicia.[20][22][30] Sayf al-Dawla's domain was a "Syro-Mesopotamian state", in the expression of the Orientalist Marius Canard, and extensive enough to require two capitals: alongside Aleppo, which became Sayf al-Dawla's main residence, Mayyafariqin was selected as the capital for the Jaziran provinces. The latter were held ostensibly in charge of his elder brother Nasir al-Dawla, but in reality, the size and political importance of Sayf al-Dawla's emirate allowed him to effectively throw off the tutelage of Nasir al-Dawla. Although Sayf al-Dawla continued to show his elder brother due deference, henceforth, the balance of power between the two would be reversed.[20][22][31]

Arab tribal revolts

[编辑]Aside from his confrontation with the Ikhshidids, Sayf al-Dawla's consolidation over his realm was challenged by the need to maintain good relations with the restive native Arab tribes.[32] Northern Syria at this time was controlled by a number of Arab tribes, who had been resident in the area since the Umayyad period, and in many cases even before that. The region around Homs was settled by the Kalb and the Tayy tribes, while the north, a broad strip of land from the Orontes until beyond the Euphrates was controlled by the still largely nomadic Qaysi tribes of Uqayl, Numayr, Ka'b and Qushayr, as well as the aforementioned Banu Kilab around Aleppo. Further south, the originally Yemeni Tanukh were settled around Maarrat al-Nu'man, while the coasts were settled by the Bahra' and Kurds.[33]

In his relations with them, Sayf al-Dawla benefitted from the fact that he was an ethnic Arab, unlike most of the contemporary rulers in the Islamic Middle East, who were Turkish or Iranian warlords who had risen from the ranks of the military slaves (ghilman). This helped him win support among the Arab tribes, and the bedouins played a prominent role in his administration.[34] However, in accordance with the usual late Abbasid practice familiar to Sayf al-Dawla and common across the Muslim states of the Middle East, the Hamdanid state was heavily reliant on and increasingly dominated by its non-Arab, mostly Turkish, ghilman. This is most evident in the composition of his army: alongside Arab tribal cavalry, which was often unreliable and driven more by plunder than loyalty or discipline, the Hamdanid armies made heavy use of Daylamites as heavy infantry, Turks as horse archers, and Kurds as light cavalry. These forces were complemented, especially against the Byzantines, by the garrisons of the Thughur, among whom were many volunteers (ghazi) from across the Muslim world.[34][35][36]

After winning recognition by the Ikhshidids, Sayf al-Dawla began a series of campaigns of consolidation. His main target was to establish firm control over the Syrian littoral, as well as the routes connecting it to the interior. The operations there included a difficult siege of the fortress of Barzuya in 947–948, which was held by a Kurdish brigand leader, who from there controlled the lower Orontes valley.[33] In central Syria, a Qarmatian-inspired revolt of the Kalb and Tayyi erupted in late 949, led by a certain Ibn Hirrat al-Ramad. The rebels enjoyed initial success, even capturing the Hamdanid governor of Homs, but they were quickly crushed.[33] In the north, the attempts of the Hamdanid administrators to keep the bedouin from interfering with the more settled Arab communities resulted in regular outbreaks of rebellion between 950 and 954, which had to be suppressed by Sayf al-Dawla's army.[33]

Finally, in spring 955 a major rebellion broke out in the region of Qinnasrin and Sabkhat al-Jabbul, which involved all tribes, both bedouin and sedentary, including the Hamdanids' close allies, the Kilab. Sayf al-Dawla was able to resolve the situation quickly, initiating a ruthless campaign of swift repression that included driving the tribes into the desert to die or capitulate, coupled with diplomacy that played on the divisions among the tribesmen. Thus the Kilab were offered peace and a return to their favoured status, and were given additional lands at the expense of the Kalb, who were evicted from their homes along with the Tayyi, and fled south to settle in the plains north of Damascus and the Golan Heights, respectively. At the same time, the Numayr were also expelled and encouraged to resettle in the Jazira around Harran.[30][33] The revolt was suppressed within the single month of June 955, in what Bianquis calls "a desert policing operation perfectly planned and rigorously executed". It was only Sayf al-Dawla's "feelings of solidarity and his sense of Arab honour", according to Bianquis, that prevented the revolt from ending with the "total extermination, through warfare and thirst, of all the tribes".[33]

The suppression of the great tribal revolt marked, in the words of historian Hugh Kennedy, "the high point of Sayf al-Dawla’s success and power",[30] and secured the submission of the bedouin tribes for the remainder of Sayf al-Dawla's reign.[33] For a short time, during that year, his suzerainty was also acknowledged in parts of Adharbayjan around Salmas, where the Kurd Daysam established brief control until evicted and finally captured by Marzuban ibn Muhammad.[33]

Wars with the Byzantines

[编辑]

Through his assumption of control over the Syrian and Jaziran borderlands (Thughur) with Byzantium in 945/6, Sayf al-Dawla emerged as the chief Arab prince facing the Byzantine Empire, and warfare with the Byzantines became his main preoccupation.[20] Indeed, much of Sayf al-Dawla's reputation stems from his unceasing, though ultimately unsuccessful war with the Empire.[31][37]

By the early 10th century, the Byzantines had gained the upper hand over their eastern Muslim neighbours. The onset of decline in the Abbasid Caliphate after 861 (the "Anarchy at Samarra") was followed by the Battle of Lalakaon in 863, which had broken the power of the border emirate of Malatya and marked the beginning the gradual Byzantine encroachment on the Arab borderlands. Although the emirate of Tarsus in Cilicia remained strong and Malatya continued to resist Byzantine attacks, over the next half-century the Byzantines managed to overwhelm the Paulician allies of Malatya and advance to the Upper Euphrates, occupying the mountains north of the city.[38][39] Finally, after 927, peace on their Balkan frontier enabled the Byzantines, under John Kourkouas, to turn their forces east and begin a series of campaigns that culminated in the fall and annexation of Malatya in 934, an event which sent shock-waves among the other Muslim emirates. Arsamosata followed in 940, and Qaliqala (Byzantine Theodosiopolis, modern Erzurum) in 949.[40][41][42]

The Byzantine advance evoked a great emotional response in the Muslim world, with volunteers, both soldiers and civilians, flocking to participate in the jihad against the Empire. Sayf al-Dawla was also affected by this atmosphere, and became deeply impregnated with the spirit of jihad.[33][34][43] The rise of the Hamdanid brothers to power in the frontier provinces and the Jazira is therefore to be regarded against the backdrop of the Byzantine threat, as well as the manifest inability of the Abbasid government to stem the Byzantine offensive.[44][45] In Hugh Kennedy's words, "compared with the inaction or indifference of other Muslim rulers, it is not surprising that Sayf al-Dawla's popular reputation remained high; he was the one man who attempted to defend the Faith, the essential hero of the time".[46]

Early campaigns

[编辑]Sayf al-Dawla entered the fray against the Byzantines in 936, when he led an expedition to the aid of Samosata, at the time besieged by the Byzantines. A revolt in his rear forced him to abandon the campaign, and he only managed to send a few supplies to the town, which fell soon after.[47][48] In 938, he raided the region around Malatya and captured the Byzantine fort of Charpete. Some Arab sources report a major victory over Kourkouas himself, but the Byzantine advance does not seem to have been affected.[47][48][49] His most important campaign in these early years was in 939–940, when he invaded southwestern Armenia and secured a pledge of allegiance and the surrender of a few fortresses from the local princes—the Muslim Kaysites of Manzikert and the Christian Bagratids of Taron and Gagik Artsruni of Vaspurakan—who had begun defecting to Byzantium, before turning west and raiding Byzantine territory up to Koloneia.[50][51][52] This expedition temporarily broke the Byzantine blockade around Qaliqala, but Sayf al-Dawla's preoccupation with his brother's wars in Iraq over the next years meant that the success was not followed up. This was a major missed chance; as the historian Mark Whittow comments, a more sustained policy could have made use of the Armenian princes' distrust of Byzantine expansionism, to form a network of clients and contain the Byzantines. Instead, the latter were given a free hand, which allowed them to press on and capture Qaliqala, cementing their dominance over the region.[44][47][53]

Failures and victories, 945–955

[编辑]

After establishing himself at Aleppo in 944, Sayf al-Dawla resumed warfare against Byzantium in 945/6. From then until the time of his death, he was the Byzantines' chief antagonist in the East—by the end of his life Sayf al-Dawla was said to have fought against them in over forty battles.[54][55] Nevertheless, despite his frequent and destructive raids against the Byzantine frontier provinces and into Asia Minor, and his victories in the field, his strategy was essentially defensive, and he never seriously attempted to challenge Byzantine control of the crucial mountain passes or conclude alliances with other local rulers in an effort to roll back the Byzantine conquests. Compared to Byzantium, Sayf al-Dawla was the ruler of a minor principality, and could not match the means and numbers available to the resurgent Empire: the contemporary Arab sources report—with obvious, but nonetheless indicative, exaggeration—that Byzantine armies numbered up to 200,000, while Sayf al-Dawla's largest force numbered some 30,000.[47][55][56]

Hamdanid efforts against Byzantium were further crippled by the dependence on the Thughur system. The fortified militarized zone of the Thughur was very expensive to maintain, requiring constant provisions of cash and supplies from other parts of the Muslim world. Once the area came under Hamdanid control, the rump Caliphate lost any interest in providing these resources, while the scorched earth tactics of the Byzantines further reduced the area's ability to feed itself. Furthermore, the cities of the Thughur were fractious by nature, and their allegiance to Sayf al-Dawla was the result of his charismatic leadership and his military successes; once the Byzantines gained the upper hand and the Hamdanid's prestige declined, the various cities tended to look out only for themselves.[57] Finally, Sayf al-Dawla's origin in the Jazira also affected his strategic outlook, and was probably responsible for his failure to construct a fleet, or to pay any attention at all to the Mediterranean, in stark contrast to most Syria-based polities in history.[30][47]

Sayf al-Dawla's raid of winter 945/6 was of limited scale, and was followed by a prisoner exchange.[47] Warfare on the frontiers then died down for a couple of years, and recommenced only in 948.[58] Despite scoring a victory over a Byzantine invasion in 948, he was unable to prevent the sack of Hadath, one of the main Muslim strongholds in the Euphrates Thughur, by Leo Phokas, one of the sons of the Byzantine Domestic of the Schools (commander-in-chief) Bardas Phokas.[47][58][59] Sayf al-Dawla's expeditions in the next two years were also failures. In 949 he raided into the theme of Lykandos but was driven back, and the Byzantines proceeded to sack Marash, defeat a Tarsian army and raid as far as Antioch. In the next year, Sayf al-Dawla led a large force into Byzantine territory, ravaging the themes of Lykandos and Charsianon, but on his return he was ambushed by Leo Phokas in a mountain pass. In what became known as the ghazwat al-musiba, the 'dreadful expedition', Sayf al-Dawla lost 8,000 men and barely escaped himself.[47][60]

Sayf al-Dawla nevertheless rejected offers of peace from the Byzantines, and launched another raid against Lykandos and Malatya, persisting until the onset of winter forced him to retire.[60] In the next year, he concentrated his attention on rebuilding the fortresses of Cilicia and northern Syria, including Marash and Hadath. Bardas Phokas launched an expedition to obstruct these works, but was defeated. Bardas launched another campaign in 953, but despite having a considerably larger force at his disposal, he was heavily defeated near Marash in a battle celebrated by Sayf al-Dawla's panegyrists. The Byzantine commander even lost his youngest son, Constantine, to Hamdanid captivity. Another expedition led by Bardas in the next year was also defeated, allowing Sayf al-Dawla to complete the re-fortification of Samosata and Hadath. The latter successfully withstood yet another Byzantine attack in 955.[47][61]

Byzantine ascendancy, 956–962

[编辑]Sayf al-Dawla's victories brought about the replacement of Bardas by his eldest son, Nikephoros Phokas. Blessed with capable subordinates like his brother Leo and his nephew John Tzimiskes, Nikephoros would bring about a reversal of fortunes in Sayf al-Dawla's struggle with the Byzantines.[47][61] The new domestic of the schools also benefited from the culmination of military reforms that created a more professional army.[62]

In spring 956, Sayf al-Dawla pre-empted Tzimiskes from a planned assault on Amida, and invaded Byzantine territory first. Tzimiskes then seized a pass in Sayf al-Dawla's rear, and attacked him during his return. The hard-fought battle, fought amidst torrential rainfall, resulted in a Muslim victory as Tzimiskes lost 4,000 men. At the same time, however, Leo Phokas invaded Syria and defeated and captured Sayf al-Dawla's cousin Abu'l-'Asha'ir, whom he had left behind in his stead. Later in the year, Sayf al-Dawla was obliged to go to Tarsus to help repel a raid by the Byzantine Cibyrrhaeot fleet.[47][61] In 957, Nikephoros took and razed Hadath, but Sayf al-Dawla was unable to react as he discovered a conspiracy by some of his officers to surrender him to the Byzantines in exchange for money. Sayf al-Dawla executed 180 of his ghilman and mutilated over 200 others in retaliation.[47][64] In the next spring, Tzimiskes invaded the Jazira, captured Dara, and scored a victory at Amida over an army of 10,000 led by one of Sayf al-Dawla's favourite lieutenants, the Circassian Nadja. Together with the parakoimomenos Basil Lekapenos, he then stormed Samosata, and even inflicted a heavy defeat on a relief army under Sayf al-Dawla himself. The Byzantines exploited Hamdanid weakness, and in 959 Leo Phokas led a raid as far as Cyrrhus, sacking several forts on his way.[47][65]

In 960, Sayf al-Dawla tried to use the absence of Nikephoros Phokas with much of his army on his Cretan expedition, to re-establish his position. At the head of a large army, he invaded Byzantine territory and sacked the fortress of Charsianon. On his return, however, his army was attacked and almost annihilated in an ambush by Leo Phokas and his troops. Once again, Sayf al-Dawla managed to escape, but his military power was broken. The local governors now began to make terms with the Byzantines on their own, and the Hamdanid's authority was increasingly questioned even in his own capital.[56][66][67] Sayf al-Dawla now needed time, but as soon as Nikephoros Phokas returned victorious from Crete in summer 961, he began preparations for his next campaign in the east. The Byzantines launched their attack in the winter months, catching the Arabs off guard. They captured Anazarbus in Cilicia, and followed a deliberate policy of devastation and massacre to drive the Muslim population away. After Nikephoros repaired to Byzantine territory to celebrate Easter, Sayf al-Dawla entered Cilicia and claimed direct control over the province. He began to rebuild Anazarbus, but the work was left incomplete when Nikephoros recommenced his offensive in autumn, forcing Sayf al-Dawla to depart the region.[68][69] The Byzantines, with an army reportedly 70,000 strong, proceeded to take Marash, Sisium, Duluk and Manbij, thereby securing the western passes over the Anti-Taurus Mountains. Sayf al-Dawla sent his army north under Nadja to meet the Byzantines, but Nikephoros ignored them. Instead, the Byzantine general led his troops south and in mid-December, they suddenly appeared before Aleppo. After defeating an improvised army before the city walls, the Byzantines stormed the city and plundered it, except for the citadel, which continued to hold out. The Byzantines departed, taking some 10,000 inhabitants, mostly young men, with them as captives. Returning to his ruined and half-deserted capital, Sayf al-Dawla repopulated it with refugees from Qinnasrin.[68][70][71][72] The latter city was abandoned, resulting in a major blow to commerce in the region.[68]

Illness, rebellions and death

[编辑]In 963, the Byzantines remained quiet as Nikephoros was scheming to ascend the imperial throne,[73] but Sayf al-Dawla suffered the loss of his sister, Khawla Sitt al-Nas, and was troubled by the onset of hemiplegia as well as worsening intestinal and urinary disorders, which henceforth confined him to a litter.[68] The disease limited Sayf al-Dawla's ability to intervene personally in the affairs of his state; he soon abandoned Aleppo to the charge of his chamberlain, Qarquya, and spent most of his final years in Mayyafariqin, leaving his senior ghilman to carry the burden of warfare against the Byzantines and the various rebellions that sprung up in his domains. Sayf al-Dawla's physical decline, coupled with his military failures, especially the capture of Aleppo in 962, meant that his authority became increasingly shaky among his subordinates, for whom military success was the prerequisite for political legitimacy.[68][74]

Thus, in 961, the emir of Tarsus, Ibn az-Zayyat, unsuccessfully tried to turn over his province to the Abbasids. In 963, his nephew, the governor of Harran, Hibat Allah, rebelled after killing Sayf al-Dawla's trusted Christian secretary in favour of his father, Nasir al-Dawla.[68] Nadja was sent to subdue the rebellion, forcing Hibat Allah to flee to his father's court, but then Nadja himself rebelled and attacked Mayyafariqin, defended by Sayf al-Dawla's wife, with the intention of turning it over to the Buyids. He failed, and retreated to Armenia, where he managed to take over a few fortresses around Lake Van. In autumn 964 he again attempted to take Mayyafariqin, but was obliged to abandon it to subdue a revolt in his new Armenian domains. Sayf al-Dawla himself travelled to Armenia to meet his former lieutenant. Nadja re-submitted to his authority without resistance, but was murdered in winter 965 at Mayyafariqin, probably at the behest of Sayf al-Dawla's wife.[68] At the same time, Sayf al-Dawla pursued an alliance with the Qarmatians of Bahrayn, who were active in the Syrian Desert, and opposed both to the Buyids of Iraq and to the Ikhshidids of Egypt.[68]

Nevertheless, despite his illness and the spreading famine in his domains, in 963 Sayf al-Dawla launched three raids into Asia Minor. One of them even reached as far as Iconium, but Tzimiskes, named Nikephoros' successor as Domestic of the East, responded by launching an invasion of Cilicia in winter. He destroyed an Arab army at the 'Field of Blood' near Adana, and unsuccessfully besieged Mopsuestia before lack of supplies forced him to return home. In autumn 964, Nikephoros, now emperor, again campaigned in the East, and met little resistance. Mopsuestia was besieged but held out, until the famine that plagued the province forced the Byzantines to withdraw.[68][75] Nikephoros however returned in the next year and stormed the city and deported its inhabitants. On 16 August 965, Tarsus was surrendered by its inhabitants, who secured safe passage to Antioch. Cilicia became a Byzantine province, and Nikephoros proceeded to re-Christianize it.[68][72][76]

The year 965 also saw two further large-scale rebellions within Sayf al-Dawla's domains. The first was led by a former governor of the coast, the ex-Qarmatian Marwan al-Uqayli, which grew to threatening dimensions: the rebels captured Homs, defeated an army sent against them and advanced up to Aleppo, but al-Uqayli was wounded in the battle for the city and died shortly after.[68][74] In autumn, a more serious revolt broke out in Antioch, led by the former governor of Tarsus, Rashiq ibn Abdallah al-Nasimi. The rebellion was obviously motivated by Sayf al-Dawla's inability to stop the Byzantine advance. After raising an army in the town, Rashiq led it to besiege Aleppo, which was defended by Sayf al-Dawla's ghilman, Qarquya and Bishara. Three months into the siege, the rebels had taken possession of part of the lower town, when Rashiq was killed. He was succeeded by a Daylamite named Dizbar. Dizbar defeated Qarquya and took Aleppo, but then departed the town to take control over the rest of northern Syria.[74][77] The rebellion is described in the Life of Patriarch Christopher of Antioch, an ally of Sayf al-Dawla. In the same year, Sayf al-Dawla was also heavily affected by the death of two of his sons, Abu'l-Maqarim and Abu'l-Baraqat.[68]

In early 966, Sayf al-Dawla asked for and received a short truce and an exchange of prisoners with the Byzantines, which was held at Samosata. He ransomed many Muslim captives at great cost, only to see them go over to Dizbar's forces. Sayf al-Dawla resolved to confront the rebel: carried on his litter, he returned to Aleppo, and on the next day defeated the rebel's army, helped by the defection of the Banu Kilab from Dizbar's army. The surviving rebels were ruthlessly punished.[74][78] However, Sayf al-Dawla was still unable to confront Nikephoros when he resumed his advance. The Hamdanid ruler fled to the safety of the fortress of Shayzar while the Byzantines raided the Jazira, before turning on northern Syria, where they launched attacks on Manbij, Aleppo and even Antioch, whose newly appointed governor, Taki al-Din Muhammad ibn Musa, went over to them with the city's treasury.[72][78][79] In early February 967, Sayf al-Dawla returned to Aleppo, where he died on 8 or 9 February (although a source claims that he died at Mayyafariqin). The sharif Abu Abdallah al-Aqsasi read the funeral prayers in Shi'a fashion. His body was embalmed and buried at a mausoleum in Mayyafariqin beside his mother and sister. A brick made of dust collected from his armour after his campaigns was reportedly placed under his head, according to his last will.[24][80][81] He was succeeded by his only surviving son (by his cousin Sakhinah), the fifteen-year-old Abu'l-Ma'ali Sharif, better known as Sa'd al-Dawla,[81][82] to whom Sayf al-Dawla ordered the oath of allegiance to be sworn before his death.[83][a] Sa'd al-Dawla's reign was marked by internal turmoil, and it was not until 977 that he was able to secure control of his own capital. By this time, the rump emirate was almost powerless and became a bone of contention between the Byzantines and the new power of the Middle East, the Fatimid Caliphate, that had recently conquered Egypt.[84]

Cultural activity and legacy

[编辑]and noble deeds come in proportion to the noble.

Small deeds are great in small men's eyes,

great deeds, in great men's eyes, are small.

Sayf al-Dawlah charges the army with the burden of his zeal,

which large hosts are not strong enough to bear,

And he demands of men what only he can do—

Sayf al-Dawla surrounded himself with prominent intellectual figures, most notably the great poets al-Mutanabbi and Abu Firas, the preacher Ibn Nubata, the grammarian Ibn Jinni, and the noted philosopher al-Farabi.[86][87][88] Al-Mutanabbi's time at the court of Sayf al-Dawla was arguably the pinnacle of his career as poet.[89] During his nine years at Aleppo, al-Mutanabbi wrote 22 major panegyrics to Sayf al-Dawla,[90] which, according to the Arabist Margaret Larkin, "demonstrated a measure of real affection mixed with the conventional praise of premodern Arabic poetry."[89] The celebrated historian and poet, Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, was also part of the Hamdanid court, and dedicated his major encyclopedia of poetry and songs, Kitab al-Aghani, to Sayf al-Dawla.[91] Abu Firas was Sayf al-Dawla's cousin and had been raised at his court, while Sayf al-Dawla had married his sister Sakhinah and appointed him governor of Manbij and Harran. Abi Firas accompanied Sayf al-Dawla on his wars against the Byzantines and was taken prisoner twice. It was during his second captivity in 962–966 that he wrote his famous Rumiyyat ("Roman", i.e., Byzantine) poems.[92][93] Sayf al-Dawla's patronage of poets had a useful political dividend too: it was part of a court poet's duty to his patron to celebrate him in his work, and poetry helped spread the influence of Sayf al-Dawla and his court far across the Muslim world.[94] If Sayf al-Dawla paid special favour to poets, his court contained scholars versed in religious studies, history, philosophy and astronomy as well, so that, as S. Humphreys comments, "in his time Aleppo could certainly have held its own with any court in Renaissance Italy".[3][34] The Hamdanid emir himself probably also knew Greek, and was conversant with Ancient Greek culture.[24]

叙利亚至赛弗·道莱时代时仍是坚定的逊尼派地区,但这位君主却推崇什叶派十二伊玛目派[34]。During his reign, the founder of the Alawite sect, al-Khasibi, benefited from Sayf al-Dawla's patronage. Al-Khasibi turned Aleppo into the stable centre of his new sect, and sent preachers from there as far as Persia and Egypt with his teachings. 他的主要神学著作《伟大指引之书》(Kitab al-Hidaya al-Kubra)就是题献给赛弗·道莱的[95]。赛弗·道莱还在阿勒颇城墙外靠近一座基督教修道院处修建了伊玛目侯赛因之子穆海辛(Muhassin)的陵墓,称之为“讲坛圣陵(Mashhad al-Dikka)”[96][83]。 In the aftermath of the 962 sack of Aleppo, he invited Alid sharifs from Qum and Harran to settle in his capital.[83] Sayf al-Dawla's active promotion of Shi'ism began a process whereby Syria came to host a large Shi'a population by the 12th century.[34]

In addition, Sayf al-Dawla played a crucial role in the history of the two cities he chose as his capitals, Aleppo and Mayyafariqin. His choice raised them from obscurity to the status of major urban centres; Sayf al-Dawla lavished attention on them, endowing them with new buildings, as well as taking care of their fortification. Aleppo especially benefited from Sayf al-Dawla's patronage: of special note is the great palace of Halba outside Aleppo, as well as the gardens and aqueduct which he built there. Aleppo's rise to the chief city in northern Syria dates from his reign.[22][31]

Political legacy

[编辑]

Sayf al-Dawla has remained to modern times one of the best-known medieval Arab leaders. His bravery and leadership of the war against the Byzantines, despite the heavy odds against him, his literary activities and patronage of poets which lent his court an unmatched cultural brilliance, the calamities which struck him towards his end—defeat, illness and betrayal—have made him, in the words of Bianquis, "from his time until the present day", the personification of the "Arab chivalrous ideal in its most tragic aspect".[3][97][98]

Sayf al-Dawla's military record was, in the end, one of failure: the Byzantine advance continued after his death, culminating in the fall of Antioch in 969. Aleppo was transformed into a vassal state tributary to Byzantium, and for the next fifty years it would become the bone of contention between the Byzantines and a new Muslim power, the Egypt-based Fatimid Caliphate.[81][99] In retrospect, the Hamdanids' military defeat was inevitable, given the disparity of strength and resources with the Empire.[47] This weakness was compounded by the failure of Nasir al-Dawla to support his brother in his wars against Byzantium, by the Hamdanids' preoccupation with internal revolts, and the feebleness of their authority over much of their domains. As the historian Mark Whittow comments, Sayf al-Dawla's martial reputation often masks the reality that his power was "a paper tiger, short of money, short of soldiers and with little real base in the territories he controlled".[100] The defeat and expulsion of several Arab tribes in the great revolt of 955 also had unforeseen long-term consequences, as it left the Banu Kilab as the dominant Arab tribe in northern Syria. Associating themselves with the Hamdanids as auxiliaries, the Kilab managed to infiltrate the local cities, opening the path to their takeover of the emirate of Aleppo under the Mirdasid dynasty in the 11th century.[33]

A number of distinguished officials served as his viziers, starting with Abu Ishaq Muhammad ibn Ibrahim al-Karariti, who had previously been in Abbasid employ. He was succeeded by Abu Abdallah Muhammad ibn Sulayman ibn Fahd, and finally by the celebrated Abu'l-Husayn Ali ibn al-Husayn al-Maghribi.[83] In the position of qadi of Aleppo, the Hamdanid emir dismissed the incumbent, Abu Tahir Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Mathil, and appointed Abu Husayn Ali ibn Abdallah al-Raqqi in his stead. When the latter was killed by the Byzantines in 960, Ibn Mathil was restored, and later succeeded by Abu Ja'far Ahmad ibn Ishaq al-Hanafi.[83] While fiscal and military affairs were centralized in the two capitals of Aleppo and Mayyafariqin, but local government was based on fortified settlements, which were entrusted by Sayf al-Dawla to relatives or close associates.[33]

The picture presented by his contemporaries on the impact of Sayf al-Dawla's policies on his own domains is not favourable. Despite the Hamdanids' origins among the Arab bedouin, the Hamdanid emirate of Aleppo was a highly centralized state on the model of other contemporary Islamic polities, relying on a standing, salaried army of Turkish ghilman and Daylamite infantry which required enormous sums. This led to heavy taxation, as well as massive confiscation of private estates to sustain the Hamdanid military.[98][101] The 10th-century chronicler Ibn Hawqal, who travelled the Hamdanid domains, paints a dismal picture of economic oppression and exploitation of the common people, linked with the Hamdanid practice of expropriating extensive estates in the most fertile areas and practising a monoculture of cereals destined to feed the growing population of Baghdad. This was coupled with heavy taxation—Sayf al-Dawla and Nasir al-Dawla are said to have become the wealthiest princes in the Muslim world—which allowed them to maintain their lavish courts, but at a heavy price to their subjects' long-term prosperity.[83] According to Hugh Kennedy "even the capital of Aleppo seems to have been more prosperous under the following Mirdasid dynasty than under the Hamdanids",[98] while Bianquis claims that Sayf al-Dawla's wars and economic policies both contributed to a permanent alteration in the landscape of the regions they ruled: "by destroying orchards and peri-urban market gardens, by enfeebling the once vibrant polyculture and by depopulating the sedentarised steppe terrain of the frontiers, the Hamdanids contributed to the erosion of the deforested land and to the seizure by semi-nomadic tribes of the agricultural lands of these regions in the 11th century".[83]

Notes

[编辑]- ^ Apart from Sa'd al-Dawla, only a daughter, Sitt al-Nas, survived her father. Bianquis 1997,第109頁.

References

[编辑]- ^ Ibn Khallikan. De Slane, Mac Guckin , 编. Ibn Khallikan's Biographical Dictionary, Volume 1. Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. 1842: 404.

- ^ Canard (1971), p. 126

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Bianquis 1997,第103頁.

- ^ Özaydin 2009,第35頁.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Canard 1971,第126頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第265–266頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第266, 269頁.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Bianquis 1997,第104頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第266, 268頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第266–267頁.

- ^ Canard 1971,第126–127頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第267–268頁.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Canard 1971,第127頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第268頁.

- ^ Bianquis 1997,第104, 107頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第192–195頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第195–196頁.

- ^ 18.0 18.1 Kennedy 2004,第270頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第270–271頁.

- ^ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 Canard 1971,第129頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第196, 312頁.

- ^ 22.00 22.01 22.02 22.03 22.04 22.05 22.06 22.07 22.08 22.09 Bianquis 1997,第105頁.

- ^ Bianquis 1993,第115頁.

- ^ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Özaydin 2009,第36頁.

- ^ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Kennedy 2004,第273頁.

- ^ Bianquis 1998,第113–114頁.

- ^ Bianquis 1998,第114–115頁.

- ^ Bianquis 1998,第114, 115頁.

- ^ Bianquis 1997,第105, 107頁.

- ^ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Kennedy 2004,第274頁.

- ^ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Humphreys 2010,第537頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第273–274頁.

- ^ 33.00 33.01 33.02 33.03 33.04 33.05 33.06 33.07 33.08 33.09 33.10 Bianquis 1997,第106頁.

- ^ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 34.5 Humphreys 2010,第538頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第269, 274–275頁.

- ^ McGeer 2008,第229–242頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第275頁.

- ^ Toynbee 1973,第110–111, 113–114, 378–380頁.

- ^ Whittow 1996,第310–316, 329頁.

- ^ Toynbee 1973,第121, 380–381頁.

- ^ Treadgold 1997,第479–484頁.

- ^ Whittow 1996,第317–322頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第277–278頁.

- ^ 44.0 44.1 Kennedy 2004,第276頁.

- ^ Whittow 1996,第318頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第278頁.

- ^ 47.00 47.01 47.02 47.03 47.04 47.05 47.06 47.07 47.08 47.09 47.10 47.11 47.12 47.13 Bianquis 1997,第107頁.

- ^ 48.0 48.1 Treadgold 1997,第483頁.

- ^ Whittow 1996,第318–319頁.

- ^ Ter-Ghewondyan 1976,第84–87頁.

- ^ Treadgold 1997,第483–484頁.

- ^ Whittow 1996,第319–320頁.

- ^ Whittow 1996,第320, 322頁.

- ^ Bianquis 1997,第106–107頁.

- ^ 55.0 55.1 Whittow 1996,第320頁.

- ^ 56.0 56.1 Kennedy 2004,第277頁.

- ^ McGeer 2008,第244–246頁.

- ^ 58.0 58.1 Whittow 1996,第322頁.

- ^ Treadgold 1997,第488–489頁.

- ^ 60.0 60.1 Treadgold 1997,第489頁.

- ^ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Treadgold 1997,第492頁.

- ^ On the nature of these reforms, cf. Whittow 1996,第323–325頁

- ^ The description of this ceremony survives in De Ceremoniis, 2.19. McCormick 1990,第159–163頁

- ^ Treadgold 1997,第492–493頁.

- ^ Treadgold 1997,第493頁.

- ^ Bianquis 1997,第107–108頁.

- ^ Treadgold 1997,第495頁.

- ^ 68.00 68.01 68.02 68.03 68.04 68.05 68.06 68.07 68.08 68.09 68.10 68.11 Bianquis 1997,第108頁.

- ^ Treadgold 1997,第495–496頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第277, 279頁.

- ^ Treadgold 1997,第496–497頁.

- ^ 72.0 72.1 72.2 Whittow 1996,第326頁.

- ^ Treadgold 1997,第498–499頁.

- ^ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 Kennedy 2004,第279頁.

- ^ Treadgold 1997,第499頁.

- ^ Treadgold 1997,第500–501頁.

- ^ Bianquis 1997,第108–109頁.

- ^ 78.0 78.1 Bianquis 1997,第108, 109頁.

- ^ Treadgold 1997,第501–502頁.

- ^ Bianquis 1997,第103, 108, 109頁.

- ^ 81.0 81.1 81.2 Kennedy 2004,第280頁.

- ^ El Tayib 1990,第326頁.

- ^ 83.0 83.1 83.2 83.3 83.4 83.5 83.6 Bianquis 1997,第109頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第280–282頁.

- ^ van Gelder 2013,第61頁.

- ^ Humphreys 2010,第537–538頁.

- ^ Kraemer 1992,第90–91頁.

- ^ For a full list of the scholars associated with Sayf al-Dawla's court, cf. Bianquis 1997,第103頁; Brockelmann, Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur, Vol. I, pp. 86ff., and Supplement, Vol. I, pp. 138ff.

- ^ 89.0 89.1 Larkin 2006,第542頁.

- ^ Hamori 1992,第vii頁.

- ^ Ahmad 2003,第179頁.

- ^ Kraemer 1992,第90頁.

- ^ El Tayib 1990,第315–318, 326頁.

- ^ Bianquis 1997,第103–104頁.

- ^ Moosa 1987,第264頁.

- ^ Amabe 2016,第64頁.

- ^ Humphreys 2010,第537–539頁.

- ^ 98.0 98.1 98.2 Kennedy 2004,第265頁.

- ^ Whittow 1996,第326–327頁.

- ^ Whittow 1996,第334頁.

- ^ Amabe 2016,第57頁.

Bibliography

[编辑]- Ahmad, Zaid. [[[:Template:Gbooks]] The Epistemology of Ibn Khaldūn] 请检查

|url=值 (帮助). London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon. 2003. ISBN 978-0-203-63389-2. - Amabe, Fukuzo. [[[:Template:Gbooks]] Urban Autonomy in Medieval Islam: Damascus, Aleppo, Cordoba, Toledo, Valencia and Tunis] 请检查

|url=值 (帮助). Leiden and Boston: Brill. 2016. ISBN 978-90-04-31026-1. - Bianquis, Thierry. Mirdās, Banū or Mirdāsids. Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P.; Pellat, Ch. (编). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 115–122. 1993. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Bianquis, Thierry. Sayf al-Dawla. Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P.; Lecomte, G. (编). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 103–110. 1997. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- Bianquis, Thierry. [[[:Template:Gbooks]] Autonomous Egypt from Ibn Ṭūlūn to Kāfūr, 868–969] 请检查

|chapter-url=值 (帮助). Petry, Carl F. (编). The Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume 1: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1998: 86–119. ISBN 0-521-47137-0 (英语). - Canard, Marius. Ḥamdānids. Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch.; Schacht, J. (编). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 126–131. 1971. OCLC 495469525.

- El Tayib, Abdullah. Abū Firās al-Ḥamdānī. Ashtiany, Julia; Johnstone, T. M.; Latham, J. D.; Serjeant, R. B.; Smith, G. Rex (编). ʿAbbasid Belles-Lettres. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1990: 315–327. ISBN 978-0-521-24016-1.

- Hamori, Andras. The Composition of Mutanabbī's Panegyrics to Sayf Al-Dawla. Leiden and New York: BRILL. 1992. ISBN 978-90-04-09366-9.

- Humphreys, Stephen. Syria. Robinson, Chase F. (编). The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2010: 506–540. ISBN 978-0-521-83823-8.

- Ibn Khallikan. Ibn Khallikan's Biographical Dictionary, Translated from the Arabic. Vol. I. 由Baron Mac Guckin de Slane翻译. Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. 1842 (英语).

- Kennedy, Hugh. The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century Second. Harlow: Longman. 2004. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Kraemer, Joel L. Humanism in the Renaissance of Islam: The Cultural Revival During the Buyid Age 2nd Revised. Leiden: BRILL. 1992. ISBN 978-90-04-09736-0.

- Larkin, Margaret. Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Meri, Josef W. (编). Medieval Islamic civilization, an Encyclopedia. Vol. 1, A–K, Index. New York: Routledge: 542–543. 2006. ISBN 978-0-415-96691-7.

|article=和|title=只需其一 (帮助) - McCormick, Michael. Eternal Victory: Triumphal Rulership in Late Antiquity, Byzantium and the Early Medieval West. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1990. ISBN 978-0-521-38659-3.

- McGeer, Eric. Sowing the Dragon's Teeth: Byzantine Warfare in the Tenth Century. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Studies. 2008. ISBN 978-0-88402-224-4.

- Moosa, Matti. Extremist Shiites: The Ghulat Sects. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. 1987. ISBN 978-0-8156-2411-0.

- Özaydin, Abdülkerim. Seyfüddevle el-Hamdânî. TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 37 (Sevr Antlaşmasi – Suveylîh). 伊斯坦堡: 土耳其宗教事務局,伊斯蘭研究中心: 35–36. 2009年. ISBN 9789753895897 (土耳其语).

- Ter-Ghewondyan, Aram. The Arab Emirates in Bagratid Armenia. 由Nina G. Garsoïan翻译. Lisbon: Livraria Bertrand. 1976 [1965]. OCLC 490638192 (英语).

- Toynbee, Arnold. Constantine Porphyrogenitus and His World. London and New York: Oxford University Press. 1973. ISBN 978-0-19-215253-4.

- Treadgold, Warren. A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. 1997. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2 (英语).

- van Gelder, G. J. H. Classical Arabic Literature: A Library of Arabic Literature Anthology. NYU Press. 2013. ISBN 978-0-8147-3826-9.

- Whittow, Mark. The Making of Byzantium, 600–1025. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. 1996. ISBN 978-0-520-20496-6 (英语).

Further reading

[编辑]- Ayyıldız, Esat. El-Mutenebbî’nin Seyfüddevle’ye Methiyeleri (Seyfiyyât) [Al-Mutanabbī’s Panegyrics to Sayf al-Dawla (Sayfiyyāt)]. BEÜ İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi. 2020, 7 (2): 497–518. doi:10.33460/beuifd.810283 (Turkish).

- Canard, Marius. Sayf al-Daula. Recueil de textes relatifs à l'émir Sayf al-Daula le Hamdanide, avec annotations, édité par M. Canard. Algiers: J. Carbonel. 1934 (法语).

- Canard, Marius. Les H'amdanides et l'Arménie. Annales de l'Institut d'Études Orientales. 1948, VII: 77–94 [19 July 2012] (法语).

- Canard, Marius. Histoire de la dynastie des Hamdanides de Jazîra et de Syrie. Algiers: Faculté des Lettres d'Alger. 1951. OCLC 715397763 (法语).

- Garrood, William. The Byzantine Conquest of Cilicia and the Hamdanids of Aleppo, 959–965. Anatolian Studies. 2008, 58: 127–140. ISSN 0066-1546. JSTOR 20455416. doi:10.1017/s006615460000870x.

外部链接

[编辑]- al-Mutanabbi to Sayf al-Dawla. Princeton Online Arabic Poetry Project. [17 July 2012].

| 新頭銜 | Emir of Aleppo 945–967 |

繼任者: Sa'd al-Dawla |

生平

[编辑]to which al-Ikhshid's governor of Aleppo, , belonged, and entered the city unopposed in October 944.[1][2][3][4]

- ^ Full name and genealogy according to the Syria-based historian Ibn Khallikan (d. 1282): ʿAlī ibn ʾAbū l-Hayjāʾ ʿAbd Allāh ibn Ḥamdān ibn Ḥamdūn ibn al-Ḥārith ibn Lūqman ibn Rashīd ibn al-Mathnā ibn Rāfīʿ ibn al-Ḥārith ibn Ghatif ibn Miḥrāba ibn Ḥāritha ibn Mālik ibn ʿUbayd ibn ʿAdī ibn ʾUsāma ibn Mālik ibn Bakr ibn Ḥubayb ibn ʿAmr ibn Ghanm ibn Taghlib.[1]

- ^ Canard (1971), p. 129

- ^ Bianquis (1997), p. 105

- ^ Bianquis (1998), p. 113

- ^ Kennedy (2004), p. 273

引用错误:页面中存在<ref group="註">标签,但没有找到相应的<references group="註" />标签